Welcome back everybody! The last few months we’ve been looking at contemporary fiber artists, this time I thought we’d look at a tradition that is wholly North American.

Porcupine quillwork may just be the oldest form of Native American embroidery. According to Needlework Through History, it dates back to prehistoric times. This type of work was prolific among Woodland region tribes, which is also lines up with the porcupine’s natural range.

According to the Métis Museum, porcupines are nocturnal, which means they were easy to hunt during the day. The quills would be stripped before the skin had time to dry, thus insuring the quills would not become brittle. The quills would then be sorted by size, and submerged in boiling dye pots for up to four hours. Natural dyes were typically made of vegetable matter, and used wood ash or urine as a mordant. This ensured the the quills would be colorfast. Large quills would be used for background work, while smaller ones would be used for fine work.

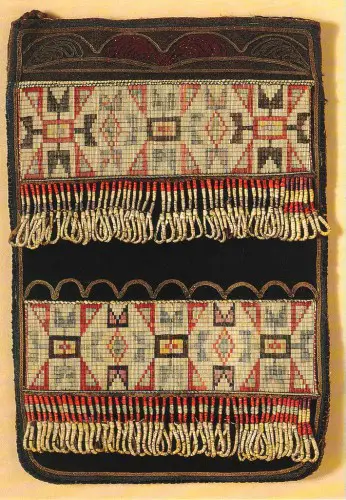

Quillwork Bag, circa 1840’s, Great Lakes area.

Quillwork Bag, circa 1840’s, Great Lakes area.

Quills cannot be used until they are softened and flattened. To prepare them, it was common for the artist to hold the quills in their mouth, softening them with saliva and then flattening them by pulling them out through their teeth. However, tools made of antler, bone or wood were also used to accomplish this. Holes were punched through the quills using an awl, and then they were stitched on to the foundation material using sinew thread. The foundation could be anything from cloth, to hide, to birch, depending on the piece.

Traditional quillwork stitches include lines, zig-zag, sawtooth, as well as wrapped edging, multiquill plaited, and loom weaving. Nativetech.org has a really thorough site that has clear pictures and instructions for quillwork.

Because we are looking at an art form that spans so many different tribes, I loathe to try to assign meaning to this technique. What might be true for the Blackfoot tribe could likely have a completely different significance to the Dene, so I won’t do my usual, “This placement means this, this color means this, this design means this.”

Cheyenne horse mask with quillwork, 1850’s.

Cheyenne horse mask with quillwork, 1850’s.

I will say however, that after 1840, glass beads became readily available and began to overtake the use of quills in most tribes. Fortunately, it has not died out. Quillwork is still found in MÃkmaq, Sioux, Cree, and Ojibway cultures among others.

MÃkmaq placemats, early 1900’s

MÃkmaq placemats, early 1900’s

Here’s a tutorial for quillwork I found on youtube, the sound’s a bit cicada-y, but overall it’s pretty good.

Anyway, this article barely scratches the surface of this tradition. I hope you click the links and read up on individual tribes to learn more!

_____________________

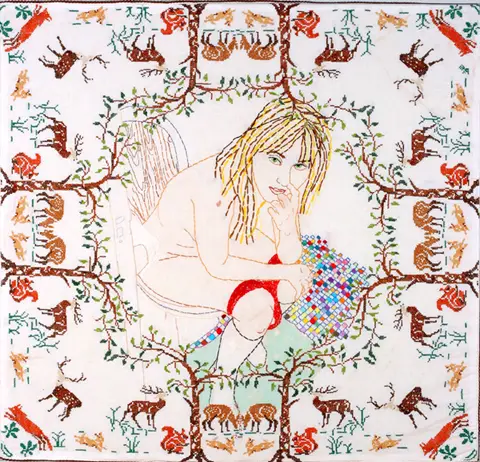

Penny Nickels is a printmaker that started playing with needles with tremendous effect. She and her husband, Johnny Murder, have been described as the “Bonnie and Clyde of Contemporary Embroidery” and you can discover the power of her creativity at her blog.

_____________________

Resources for this article include Needlework Through History by Catherine Amoroso Leslie and Embroidered Textiles by Sheila Paine.