This week we’re going to look at the history of stumpwork!

When I started researching this article, I quickly ran into some walls. Usually, I go through my oldest reference books first and see what I can dig up, but the term “stumpwork” was nowhere to be found. Eventually I made my way to Needlework Through History by Catherine Amoroso Leslie, and she tell us that “Raised embroidery is also known as raised work, embossed work, cut canvas work, and embroidery on the stamp. It did not receive the name ‘stumpwork’ until the 1890’s. stumpwork may relate to the foundation used, thus embroidering ‘on the stump.'”

Hey! These are terms I do recognize from my dusty old books! What’s interesting, is that most of my texts talk about “raised embroidery” with the occasional reference to “embroidery on the stamp”, not stump. This work seems to fall into three categories; satin stitches worked over plain stitches or wool stuffing, raised goldwork worked the same way, and then the highly dimensional stumpwork that is more sculptural than plainly stitched. In three of my books the last style seemed to be talked about derisively.

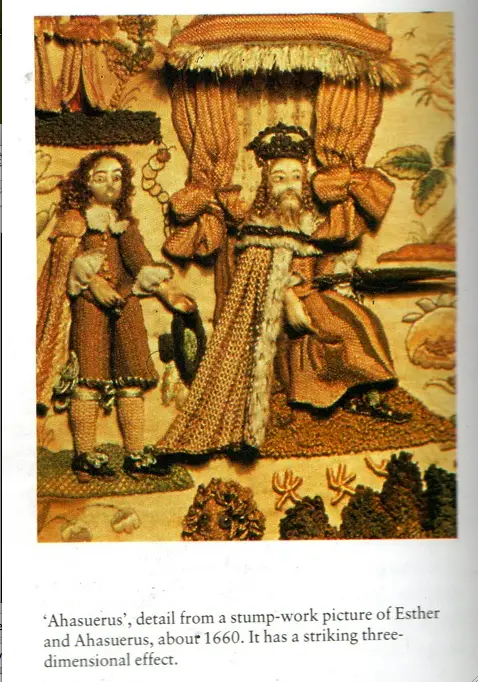

In Needlework As Art, Lady Alford says, “In the XIVth century, raised work was commonly done, but few examples are known of a date earlier than this. The raised effect is obtained by an interposed layer of padding, which is a good method of getting a certain kind of effect. It is perhaps wise to err on the side of too little than too much relief. An example of too much and also the wrong kind of English stump work that was popular in the XVIIth century, when figures were stuffed like little dolls, the clothes made separately and attached, even to the shoes and stockings. Germain de St. Aubin, writing in 1769, describes with much admiration a kind of broderie en ronde bosse, apparently much the same thing and in equally doubtful taste, though the skill to carry it out must have been considerable.”

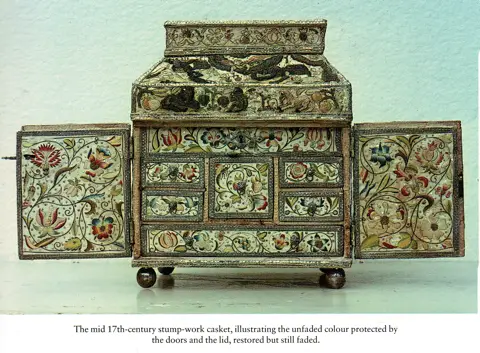

Okay, Lady! But then she pulls out stronger words. “…when James I was king, protection had done its worst. The style of work called ’embroidery on the stamp’ was then on fashion. This sort of work in Italy continued to be artistic, but the English specimens that have survived from this reign are extremely ugly.” She continues, “…the carvings of that phase of architecture were semi-barbarous. Nothing could have been poorer than their composition, or coarser than their execution, as the needlework of the day followed suit. Infinite trouble and ingenuity were wasted on looking glass frames, picture frames, and caskets worked in purl, gold, and silver. The subjects were ambitious Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, and James and Anne of Denmark, and other historical figures were stuffed with cotton or wool, and raised into high relief; and then dressed and ‘garnished’ with pearls; the faces either painted in satin or fine satin stitch; the hair and wigs in purl or complicated knotting…. The drawing and design were childish, and show us how high art can in a century or less slip back into no art at all.” Ouch.

I wonder if this was the style of decorative mirror she was talking about?

Although she is the most vocal, all of my needlework books that were published before 1915, (and I have a lot of them:) seem to focus on the more subdued form of stumpwork. They feature plenty of examples and instructions on creating the slightly raised version, and either omit or sneer at the wilder 3d form. In The Ladies Work Table Book, published in 1899, the author instructs us, “Draw the pattern on the material as before. Work the flowers, &c., to the height required, in soft cotton, taking care that the centre is much higher than the edges. A careful study of nature is indispensable to the attainment of excellence in this kind of work. Pursue the same method with your colors, as in flat embroidery, only working them much closer. The most striking effect is produced when the flowers or animals are raised, and leaves in flat embroidery. Much in this, as in every department of this charming art, must depend upon the taste and judgment ”correct or otherwise” of the fair artist. A servile copyist will never attain to excellence.“” These books seem to be warning the reader to take it easy on the fancy stumpwork, a “less is more” sentiment.

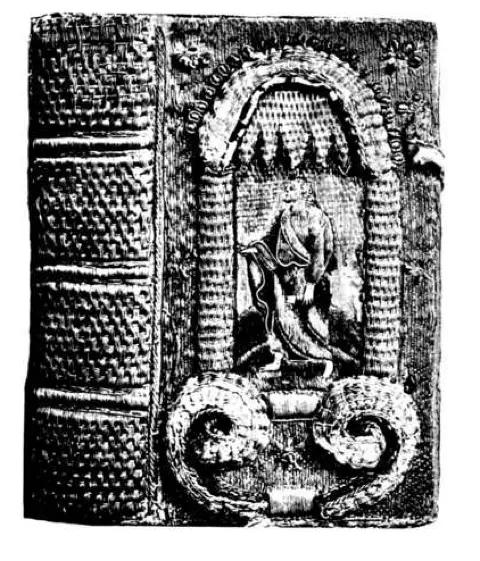

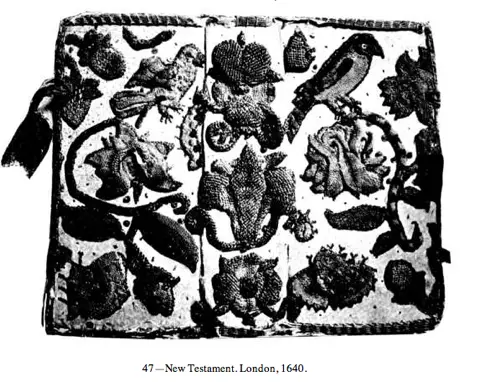

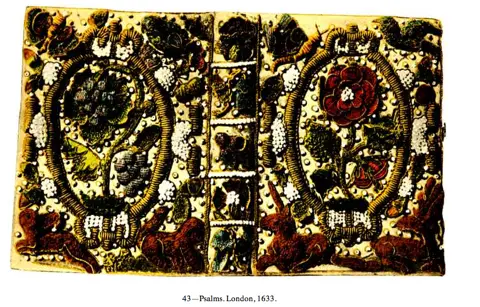

But I did find some neat examples of “More! More!!” in English Embroidered Bookbindings by Cyril Davenport 1899.

Although Cyril doesn’t expressly name the style of embroidery used in these books, he does go into great detail on materials, colors, and he pointedly describes these pieces as being worked in “high relief” embroidery.

Although Cyril doesn’t expressly name the style of embroidery used in these books, he does go into great detail on materials, colors, and he pointedly describes these pieces as being worked in “high relief” embroidery.

Even in the examples he illustrates for lack of a photograph, he takes care to give the piece obvious dimension.

Even in the examples he illustrates for lack of a photograph, he takes care to give the piece obvious dimension.

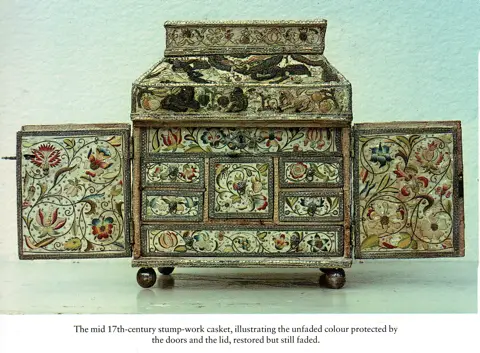

So what do we think? Sure, I understand that this work can easily be overwrought and overdone, but I kind of like it! I like the texture. And then when I see an example of it done really well-

So what do we think? Sure, I understand that this work can easily be overwrought and overdone, but I kind of like it! I like the texture. And then when I see an example of it done really well-

It kind of takes my breath away.

It kind of takes my breath away.

————–

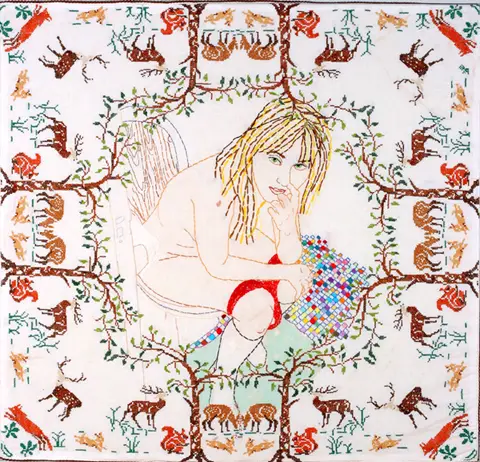

Penny Nickels is a printmaker that started playing with needles with tremendous effect. She and her husband, Johnny Murder, have been described as the “Bonnie and Clyde of Contemporary Embroidery” and you can discover the power of her creativity at her blog.———-

References for this article are cited in the text. Photos are from The Illustrated History Of Textiles by Charles Saumarez Smith and English Embroidered Bookbindings by Cyril Davenport

Zsófia Szász | Infusing tradition with new life

Zsófia Szász brings a contemporary hand to traditional Hungarian textiles. Using unconventional materials, the artist immerses new generations in craft. Read on for more!