A commenter on one of my posts recently lamented an inability to create their own designs, stating something to the effect that though they had started to really love machine embroidery, that they could never do proper embroidery digitizing, since they would never be one of those who ‘can afford to play with $4000+ ( £3053+ ) software’. The comment continued with a bit of a rant that one could never produce attractive results like the ‘professionals’ without investing in a top-of-the-line commercial package. Rather than simply point said commenter to a couple of links, I’d rather talk briefly about software, and while I’m correcting some misconceptions, give everyone who wants to digitize or just explore machine embroidery but hasn’t had a chance a little hope. With that, here are three truths about digitizing and machine embroidery that might just prove that it’s not just the playground of professionals, but that we’re really seeing a potential of machine embroidery for everyone.

Digitizing software doesn’t make you better, it makes you more efficient.

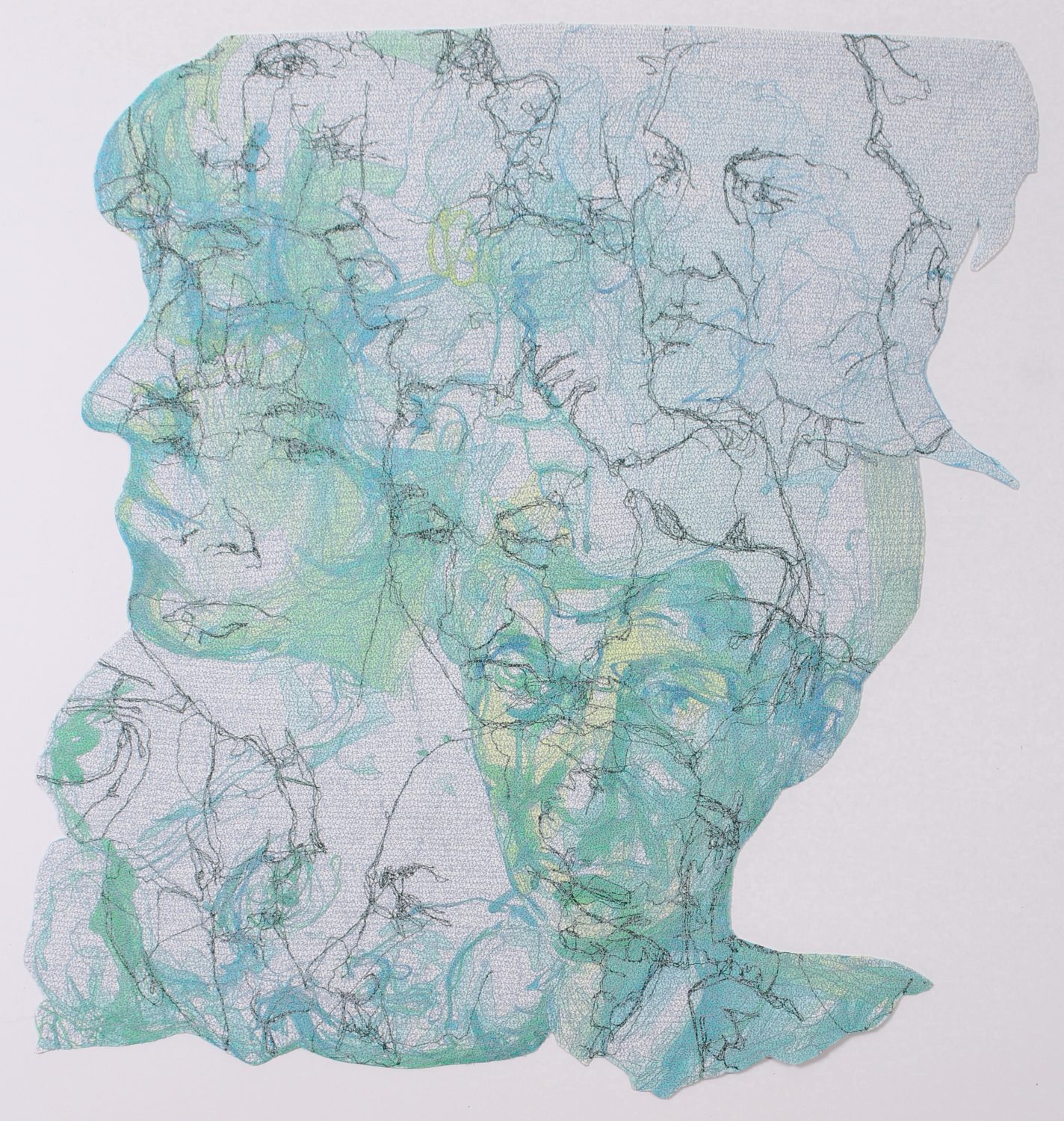

This is a well-worn statement from me, but I maintain that it is true. I won’t lie; I have used a software suite that once cost well upwards of 10K USD when it was first purchased for most of my career- much of my publicly shared work was created on the top-of-the-line software made for heavy commercial production. It came complete with a host of tools made for efficiency, including automation to quickly generate team names for mass personalization, tools to plot simple outlines around objects faster, to draw more quickly (albeit a little more roughly) with simplified splines rather than the designers’ beloved Bezier curve. That software has, a myriad of tools to make a digitizer efficient. What it doesn’t have is any ability to make artistic decisions, to draw the best shapes for you that take natural distortion into account and adjust for it in specific dimensions. It doesn’t interpret art into the best version of embroidery, reduce or alter details in ones art that won’t work well for thread as a medium, or make use of the way thread reflects light to create a piece that looks dynamic. These things are all done by a digitizer drawing shapes, selecting stitch types and angles, and layering according to their concept for how a design should look. Digitizing happens in the mind’s eye long before it happens on-screen, and the attempts any software has made toward automating this portion of the process produce pale comparisons to what a thinking person with an eye for thread can do with the same tools. Though tools exist in high-end commercial packages that allow quick artistic exploration and styling, like programmable motifs, specialty texture settings, graded permutations on standard spacing and the like, there’s nothing that these tools can do that can’t be done manually if one can plot a single stitch. If that weren’t enough many ‘home’ tools now include much, if not more, in the way of such tools for artistic styling. Though It is far more difficult to execute certain things manually, almost anything that automatic tools can do can be executed one stitch at a time or with simple automation by someone with skill who is willing to measure, prepare, draw, and plot the stitches, so long as they can imagine it and they understand the medium.

I produced one of my crowd-favorite samples that tours with me to every show and class manually, stitch by stitch, on software that ran on DOS, only displayed 16 colors, and despite the moderate automation it could do (create a fill stitch area without holes and create a simple satin stitch element), it could not draw a curve, requiring all curved items to be built of a multitude of flat-edged slices. Control made that piece successful, not automation. The truth is that machine embroidery only has a single stitch, a line from point to point, and all other stitch types are made up of stacking, layering, or chaining together these stitches. Control one stitch, learn how groups interact, conceptualize how you can make a mark with those groups, how art breaks up into stitches, and how they create a surface, and you can make any software produce the design you want. The question is only about how fast it can do so, and what other features it has to make your life with embroidery easier. If all you want to do is make embroidery designs, affordable options exist without the additional tools it takes to run a business, manage multiple machines, save job information, automate personalization, create multimedia designs, or control arcane types of machines or attachments. If you want to set stitches, there’s always a way. Becoming artistic with embroidery has more to do with exposure to embroidered art, keen analysis, and experimentation than it does with automation, though some automation absolutely makes it easier and faster to work.

Craft software is coming up.

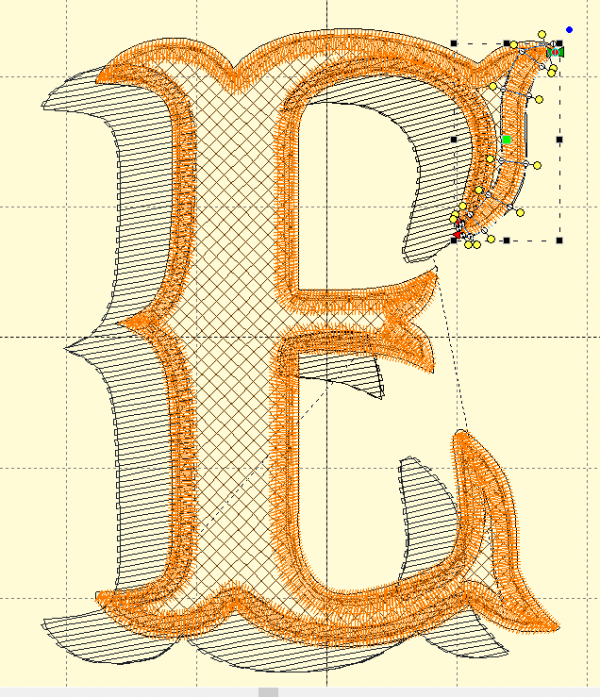

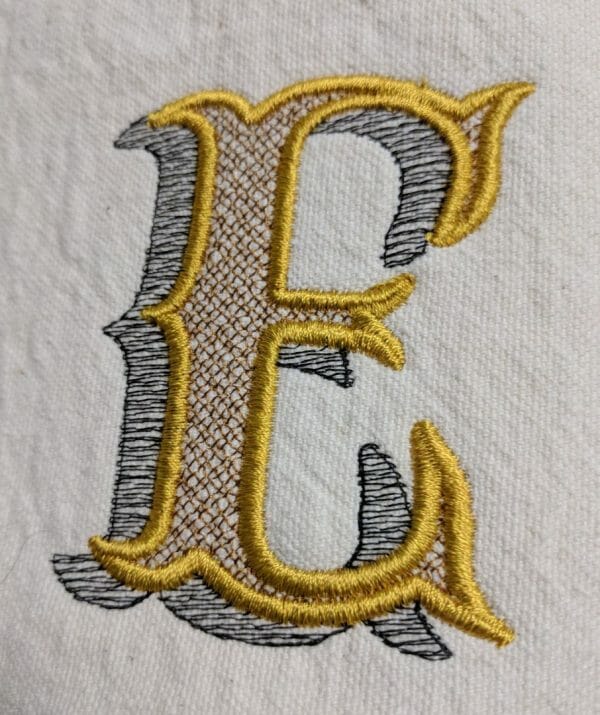

The professional software I use has a home-market sibling that sells for 25% of the cost of the full suite and has much more than 25% of the functionality. Software options have broken into the market, including one that starts at less than 10% of what the suite I used for professional production currently costs and has all the tools needed to create anything from corporate logos to artistic designs. The functionality of what has almost pejoratively been termed ‘hobbyist’ grade software has increased out of step with its price, leading to more and more commercial shops, particularly smaller or home-based businesses, employing it as a backup solution, training software, or even a complete replacement for commercial alternatives. I’ve always advocated for professional tools for the industry, but I have been shocked at how much control some ‘hobbyist’ suites have included in their products.

This democratization of tools means that those with a desire to create have access that has never before been seen in machine embroidery. Creators can much more easily find themselves steering a package that can give them semi-automated tools that far outstrip not only the horrid software i started my career with, but which nearly achieve parity with my first commercial software, even without the extended features of the latest iterations. If you have the ability and the patience, a minor investment can net you a workable solution to get your start in embroidery digitizing. Having been challenged by some friends to recreate some of my work in a traditionally home-market package that isn’t my commercial standard, I was not only able to recreate my style, I found that the tools were far more complete than I had imagined and that there were standard options in the entry level software once relegated to the highest tier of some commercial suites. What I missed from my usual tools didn’t stop me from creating the desired effect. In short, there’s never been a better time to digitize, no matter what your budget.

Machines are more accessible.

The commenter had already managed to score an embroidery machine, but for those who haven’t, you are also in for a bit of a surprise. The commercial machines I have run have their advantages, from extended embroiderable areas for large designs, to increased speeds, to better tension control, options for finished cap embroidery, and a host of attachments beyond the basic equipment, but it’s surprising how little it takes to get a reasonably serviceable machine for experimenting with flat embroidery. For those who have some disposable income, the barrier to entry for machine embroidery is no longer measured in the thousands of USD, rather a decent machine with an addressable area of 5” by 7” can be had in the range of $500-$600. I know that’s not trivial, and I’ve lived well below the means to afford such before, but it’s still a distinct difference between what was once the norm. The level of quality and capability that you can get in that range is enough to surprise me. Moreover, if you can stand the admittedly tiny stitching area of only 4 square inches, the price of a machine can drop to less than $400. These machines aren’t top of the line, and do not offer the incredible range of features to help you embroider that their cousins in the home market at multiples of these prices offer, let alone the capabilities of truly commercial machines I have had the luck to run, but they are solidly capable of producing a flat embroidery and helping you to learn your craft. The prices have decreased all along the spectrum, meaning that even commercial hardware is much more likely to find its way into the craft and hobby scenes, mingling with the multi-needle prosumer machine options from home-market machine vendors.

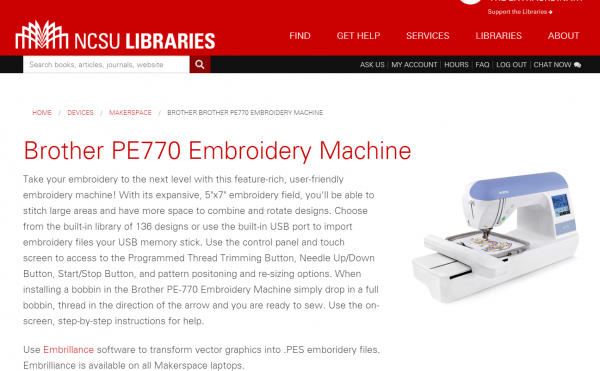

Makers are making it possible

I distinctly remember a time in my life that no amount of money could have been freed for something so outwardly frivolous as an embroidery machine, no matter how reasonable the price. For those living in similar circumstances or those just unsure that embroidery is for them, there’s now an increasing chance to experiment with embroidery for the cost of materials alone. More and more, public libraries and universities are including makerspaces as part of their offerings, and these spaces increasingly include not only home embroidery machines but occasionally have commercial hardware. Many also offer access to digitizing and embroidery software on-site. Some even host training events to familiarize the public with the basic operation of the equipment and software tools. A cursory search netted embroidery machines across multiple countries, many complete with digitizing systems, waiting for the dedicated experimenter to make their mark with thread. Combine this with the access to information that the internet can offer, from those like myself teaching what were once the closed-door secrets of the commercial trade, to those solidly in the craft and hobby market, and you start your adventure in embroidery far ahead of those of us who toiled at machines with trial-and-error experimenting just to get any acceptable result.

Research and Run

By no means is the road from rank amateur to ‘stitching sensei’ easily traversed. With all the access in the world, you’ll still be faced with a great deal of practice and require great patience to draw, digitize, and destroy garments on the way to achieving your best work. Even so, the gate that used to be closed to all but commercial professionals or those who could float massive funding for machines and software is open to more folks than it has ever been. Find out about your options, check with local libraries, study software to find the best value and support, and give it a go. You can learn to create your vision in machine embroidery and there’s more chance than ever that you won’t have to go broke or go it alone along the way.

Erich Campbell is an award-winning machine embroidery digitizer and designer and a decorated apparel industry expert as well as an industry educator appearing at several trade-shows as well as teaching online. He frequently contributies articles and interviews to embroidery industry magazines such as Printwear, Images Magazine UK, and more as well as to a host of blogs, social media groups, and other industry resources.

Erich is an evangelist for the craft, a stitch-obsessed embroidery believer, and firmly holds to constant, lifelong learning and the free exchange of technique and experience through conversations with his fellow embroiderers. A small collection of his original stock designs can be found at The Only Stitch