One of Summer 2014’s big London art exhibitions was Tate Britain’s British Folk Art show. Folk art is generally defined as things made by non-professional artists outside of the commercial art world. It isn’t really as simple as that, and this exhibition acknowledges that there’s no exact definition. What is definitely clear is that the kind of work classed as folk art rarely gets seen in a fine-art gallery context, so for Tate to show it is a big deal (for the art world). One gallery label gives the following quote, explaining much about the status of the kind of work we see in this exhibition:

At its foundation in 1768-9, The Royal Academy declared that no needlework, artificial flowers, cut paper, shell work or any such baubles should be admitted.

The RA’s influence in the art world continues to this day (although they do let in needlework and cut paper, though I wonder if artificial flowers have ever made it through the hallowed doors) and this separation of art and ‘baubles’ has defined the art world ever since. ”Baubles’ have become known as Textile art, folk art and craft – fine, contemporary or just craft.

The show contains:

- Ship figureheads

- Pincushions

- Amateur paintings

- Prisoner of war carvings

- Shop signs

- Hand painted signs

- Embroidery

- Quilts

- Corn dollies

- Samplers

- Collages

I’m delighted that there are lots of textiles in this exhibition including loads of delightful pincushions — a personal favourite. Beautiful, decorated, impractical pincushions were often made and given as gifts by lovers, both men making for women and women making for men.

This one, dated 1896 in a heart-shape is a particularly fine example. What you can’t tell from images is the size — this is huge, getting on for a foot in width (12in / 30cm) by my estimate. The silvered metal sequins have tarnished with age but the braid and pompoms remain ridiculously and wonderfully bright. Several others have not been photographed for the accompanying book, which is a shame. There’s one in velvet, similar to this and a highly decorated one made by a prisoner of war, similar to this. 18th century pincushions are usually considerably plainer than the 19th century ones previously mentioned, and there is a lovely, simple white silk one in the exhibition, similar to this.

Sailor’s wool work pictures are another exhibition strength, and some of the same items from this show can be seen in this 2011 article about an exhibition exclusively of wool work. Gunner Baldie’s picture of Sunbeam, 1875-80 is held by Compton Verney gallery, which has its own fine collection of folk art on permanent display, and will be hosting this exhibition in the autumn. Baldie’s embroidery is a cut above most of the others; the trees are particularly nicely stitched and there’s plenty of detail picked out in finer threads.

Much of the wool work on display consists of simple long stitches in quite fine crewel-type thread, with details in what appears to be cotton perle and sometimes finer silk or cotton threads, often for the rigging. There are more images and information here.

One that really stood out for me was by John Craske, a retired Norfolk fisherman who created ‘paintings with wool’ after returning from World War One with a brain abscess. The piece in the exhibition, of a sea rescue (again no image online, alas) has far more liveliness, texture and movement than most of the wool work pictures, which explains why his work was ‘discovered’ and exhibited in fine art galleries in the 1920s.

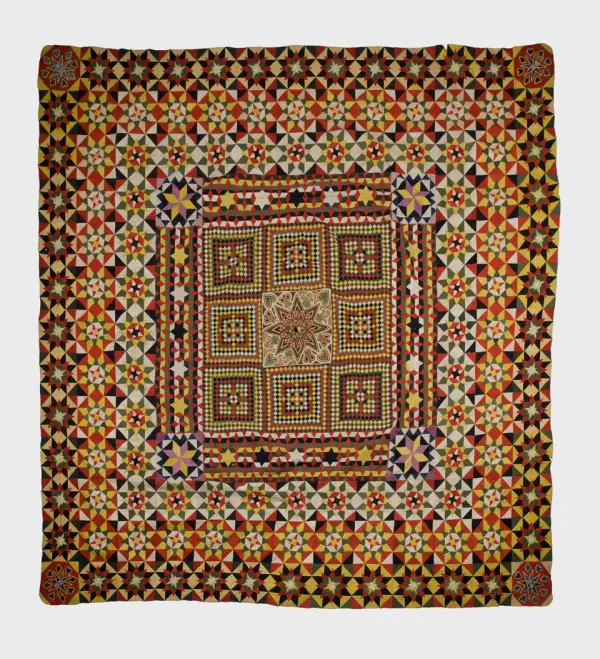

There are two well-known quilts in the show: the Wrexham quilt and the Crimean War quilt, both of which are pretty special to see in the flesh. Each is made from fine fulled wool suit / uniform fabric rather than the usual cotton used for quilts, and made entirely by men. One newspaper article I read suggested that the thickness of the wool made stitching it a manly ‘workout’, which is of course nonsense, and I suspect the writer had never stitched a thing.

Also included are two red and white quilts from Beamish Museum, one of them a strippy quilt similar to this and one a drunk Drunkard’s Path where the pattern has gone awry. The bright red fabric which doesn’t bleed into the white with washing is called Turkey Red, created from madder using a complex process. There are no photos of either quilt online but both are in the catalogue.

A number of smaller pieces of patchwork are also shown, including a lovely small panel dated early 19th century, with a lot of 18th century silk fabric scraps in it, again from Norfolk Museums. An unfinished English paper pieced hexagon quilt is also shown, reverse side up so that visitors can see the 19th century hand written papers and newspaper used as templates. Some other patchwork pincushions are also shown, though very little is said in the text about patchwork at all, which is curious given how much is included in the exhibition.

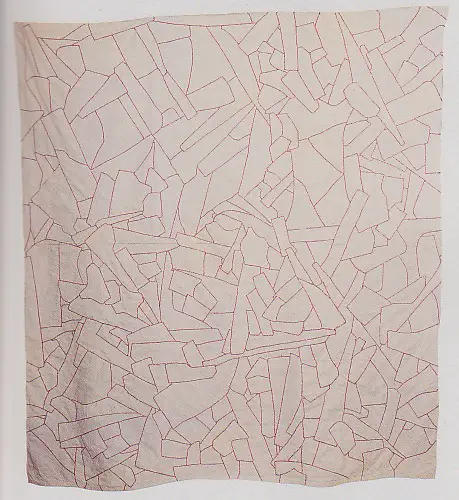

An interesting curiosity is the Clicker Quilt from Norfolk Museums, allegedly made by shoe factory workers (called Clickers) using shoe lining scraps in the 1920s. The story is too vague to be likely, but the unstuffed quilt itself is stunning, and fittingly is presented in the show as if in a gallery like fine art, although this was surely not the intention of the makers. The irregular, abstract pieces of linen it is made from don’t appear to be garment-cutting waste, and it seems unlikely that they are shoe-lining cutting waste either, as the pieces are too irregular and there are many straight lines. Whatever the pieces are, they are joined, efficiently, and neatly with feather stitch, just like multi-coloured crazy quilts of the 19th century. Image scanned from the catalogue as there’s no sign of it online.

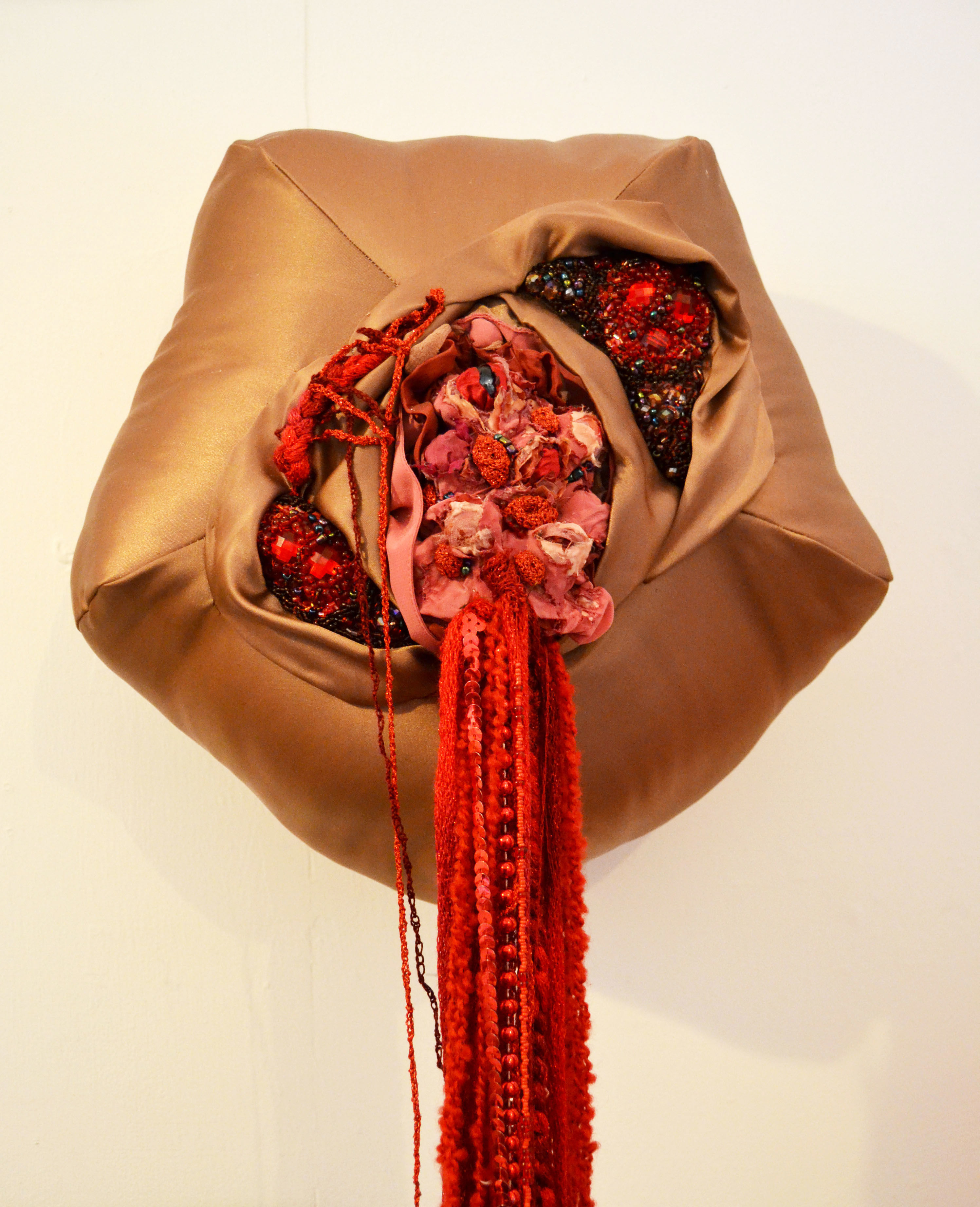

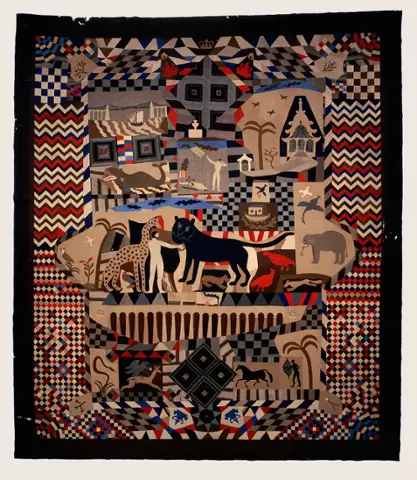

In stark contrast, the first textile piece you see on entering the exhibition is a riot of overwhelming colour. The Bellamy quilt from 1890-91 is a huge appliqué panel of velvets, heavily embroidered is bright colours with motifs of elephants, coffee pots, dancing pigs, leaves, cutlery, scissors and pretty much anything else you can think of. Subtle it is not. But it is amazing. Again, this is from Norfolk Museum Service, who, along with Tunbridge Wells Museum, seem to have great folk textile collections.

Last but not least are the embroideries of Mary Linwood (1755-1845), a local of Leicester, just like me.

Her embroidered versions of Old Master paintings were a huge commercial success in her lifetime, but were exactly the kind of work firmly rejected by the Royal Academy as mentioned earlier. The exhibition helpfully includes one piece unframed and another turned upside down so you can see the reverse — always interesting to stitchers. A label quotes a book from 1892:

Her method of work has been several times described. On an upright frame was stretched the thick tammy* woven expressly for her use. A sketch in outline of her picture was then made, and with worsteds chiefly dyed in Leicester by her manufacturing friends, and by herself, she sat to work with great energy, and worked every stitch of her pictures. The only help she had was in the threading of her needles.

William Andrews, Bygone Leicester, 1892.

Her stitching is dense and she used long, mostly straight stitches to echo painterly brushstrokes with lots of skilled shading techniques.

* Tammy is generally defined as a worsted or wool cloth, but the cloth of the two unframed pieces looked like glazed linen to me.

I stuck to the no photography rule in the exhibition, though clearly others did not and there are plenty of photos around on Instagram if you look for #britishfolkart

Fans of stitch will find lots to fascinate them in this exhibition and I do recommend visiting it before 31st August in London or later in the year at Compton Verney. I would actually suggest going to see it at Compton Verney then you can visit the permanent folk art displays at the same time – double the folk art. It is a lovely place anyway.

The accompanying small catalogue is pretty good too, but just 144 pages long. Probably half of the exhibits are featured and photographed and it is well-written with lots of fascinating information. I wish though that everything in the show was photographed and listed in the book. It also has no index which is immensely frustrating, though it does have museum information for each item in the book (though not those that didn’t get into the book).

—–

Ruth Singer Books – Get yours from our Amazon store!

– Get yours from our Amazon store!

[column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

[/column]

[column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

[/column]

[column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

[/column]