Welcome to eMbroidery, a series of interviews with male embroiderers. This month, David Curcio.

Name: David Curcio

Location: Watertown, MA.

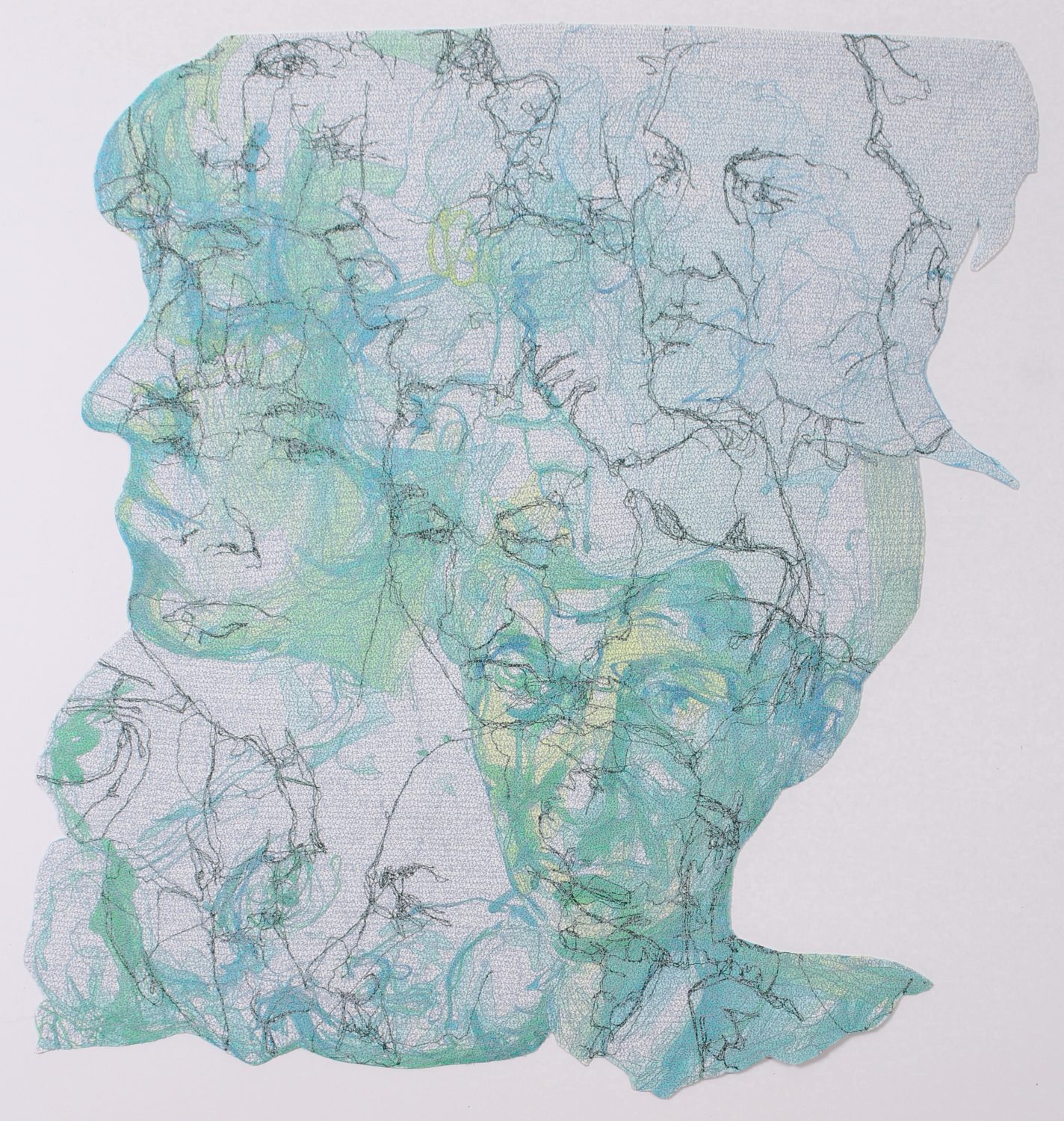

Preferred embroidery medium: Embroidery floss on Japanese paper.

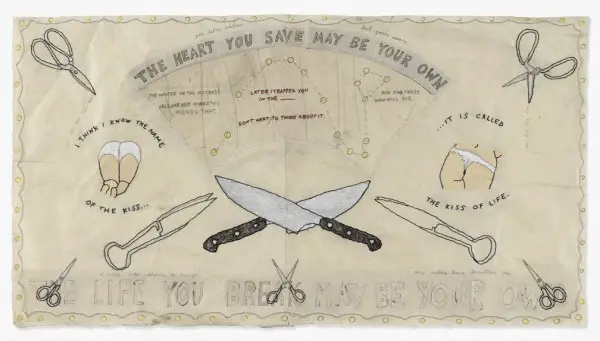

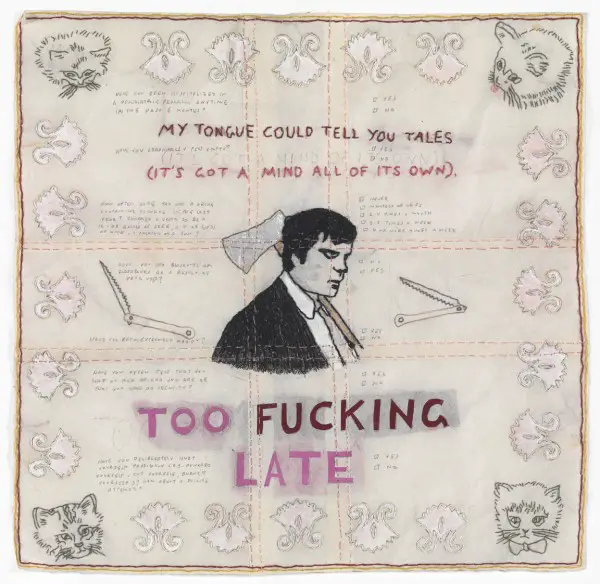

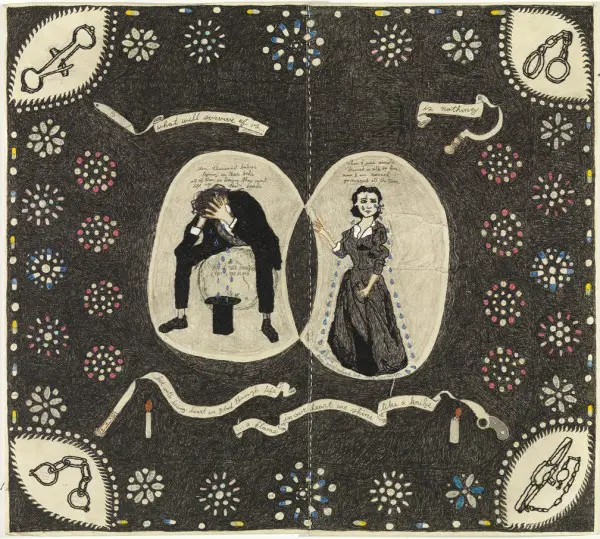

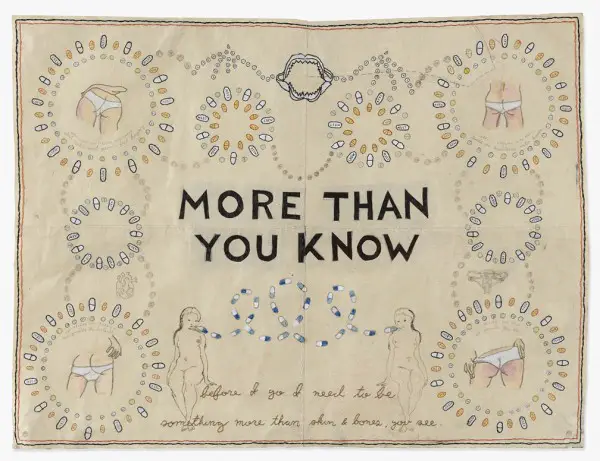

Noteworthy projects: A series entitled I Wouldn’t Worry About It featuring mixed media embroidery pieces (incorporating printmaking, ink and gouache) with imagery of Abraham Lincoln, knives and razors, and women’s panty-clad bottoms. (Completed during 2011-2012)

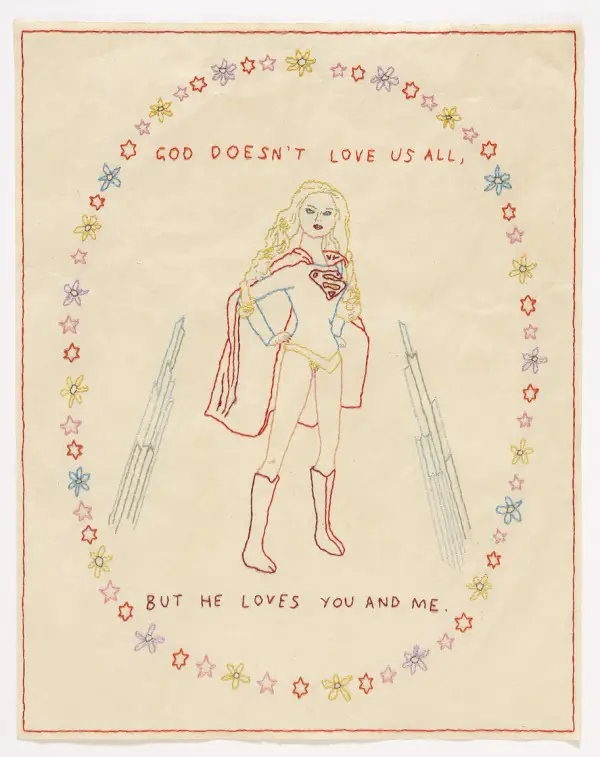

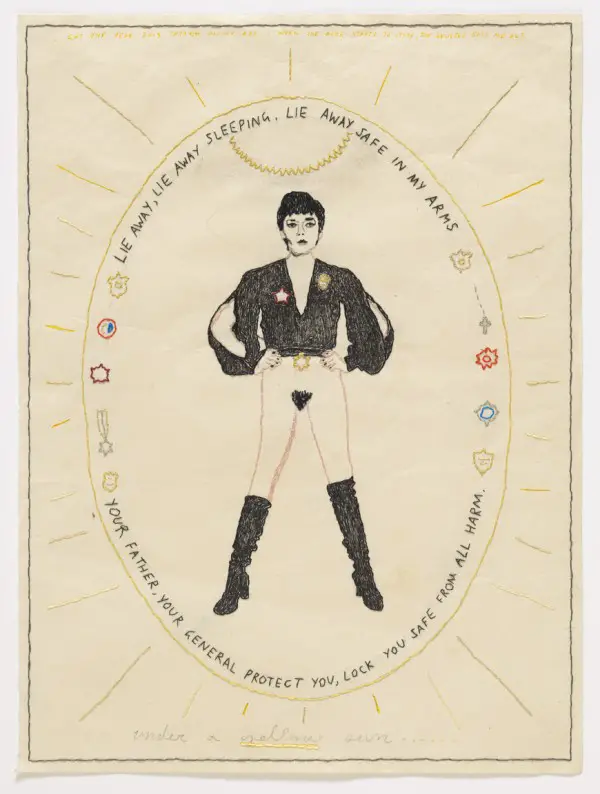

A current series in progress entitled “The Glittering World” depicting a variety of powerful women (mostly superheroes).

How did you come to be an embroiderer? I have been an admirer of outsider art and early American folk quilts for many years, and I wanted to capture that naiveté in my own work. However, with an MFA in printmaking, I am somewhat over-trained – the very opposite of the self-taught artists I was looking at. Realizing it was impossible, as well as disingenuous, to ape a naïve style, I began working with thread, which was completely out of my comfort zone. I started with the most basic of stitching and gradually moved into embroidery, first incorporating it into mixed media work with printmaking and drawing, and recently working in straight embroidery. I have obviously become more comfortable and confident with the medium over the years, and so these days working outside my comfort level involves the imagery more than the medium.

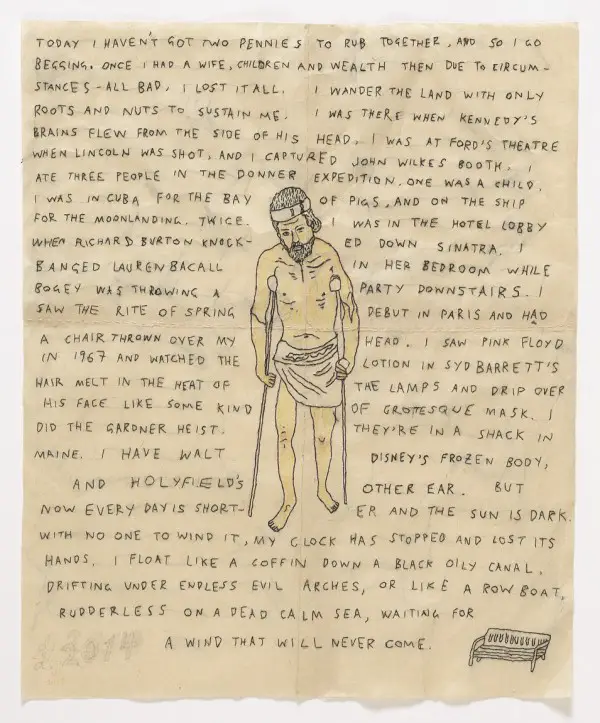

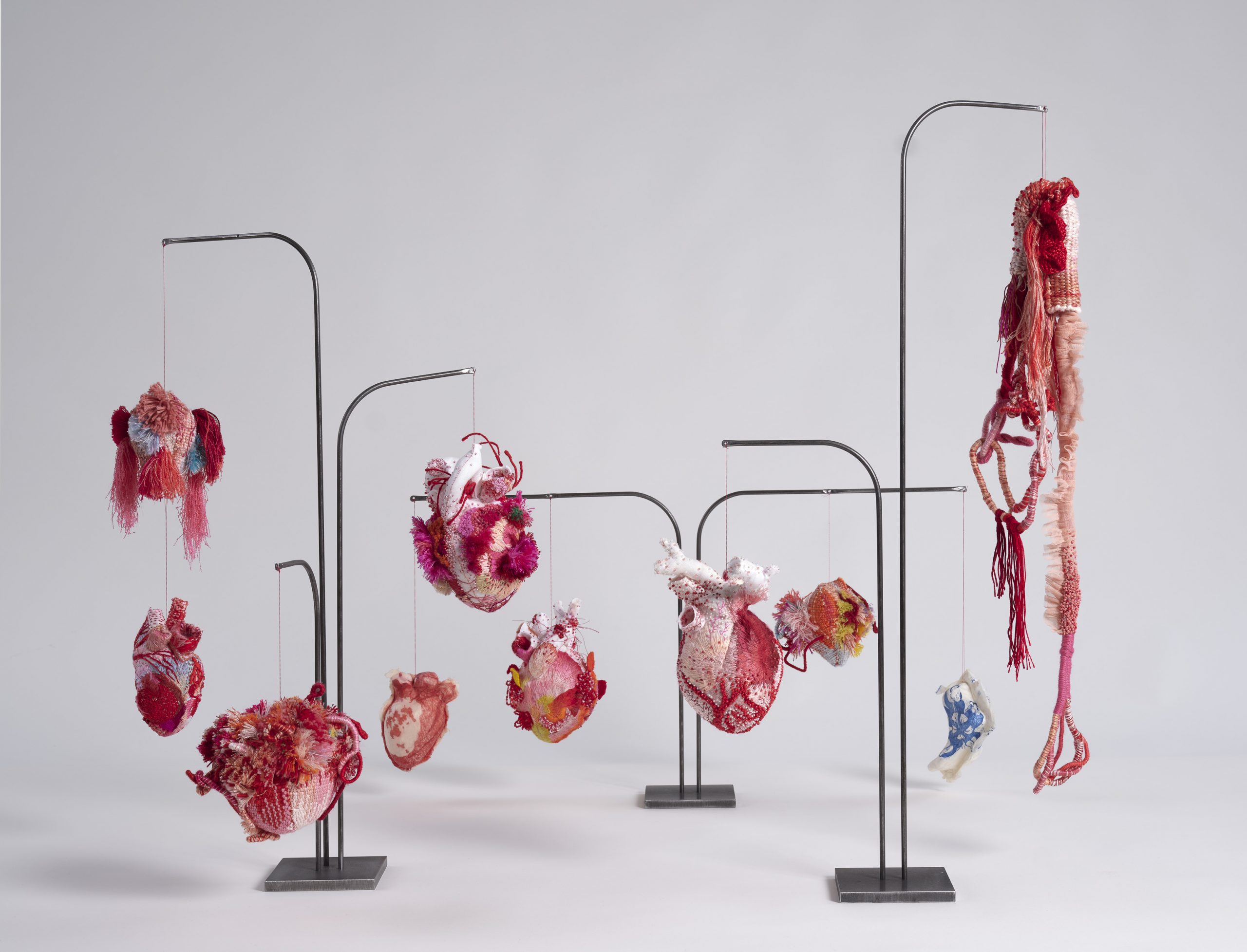

What does it mean to you? Being an embroiderer means nothing more to me than if I were a painter. As to the work, I sometimes can’t tell until several days, weeks or months after completing a piece if it says what I want it to, though sometimes I know immediately. I try to create time capsules of emotions, life conflicts or obsessions (old and new) preserved as images, in many ways readable only to me. However, I think that the visual appeal and cryptic images and text allow viewers to draw their own personal meanings from the work.

Where do you like to work? At home. I have a large etching studio where I can work as well, but with a clean medium like embroidery it is easy to work on a table at home in the company of cats, music, and an espresso machine.

How do people respond to you as a male embroiderer? It is almost exclusively women who comment or question my preferred medium, and they generally read too much into it. They see a heterosexual male with big hands who boxes working in a “delicate” medium, and it seems anachronistic. Fine. Viewers can think and speculate all they want. Maybe I am sensitive and in touch with my feminine side, but that’s expressed in the imagery, not the medium.

Who inspires you? As I mentioned, Early American folk art, particularly quilts, got me started with thread, but my biggest inspirations have come from a disparate mix of artists, Edvard Munch being my greatest influence, and the artist who has attracted me since I was a child. From there I can list many artistic influences, only two of whom have worked in fiber arts as far as I know (Kiki Smith and some late works by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner). Other influences include Cranach, the German Expressionists, Ensor, Goya, Cassatt’s aquatints, Marlene Dumas, several novels and recently, comic books.

How or where did you learn you learn how to stitch or sew? I began teaching myself about six years ago. Many people (all women) have offered to give me some instruction (one even gave me a sewing machine) but I’ve refused all assistance. I have developed a style and method with which I am comfortable, and see no reason to rock the boat until I feel it needs rocking.

Are your current images new ones or have you used them before? While there are clear themes running throughout some of the imagery, I never recycle the same image, or attempt to embroider a work previously composed in another medium. Each piece has to be fresh and new to hold my interest.

How has your life shaped or influenced your work? Everything in my life, everything that crosses my conscience, is grist for the mill. The series I Wouldn’t Worry About It dealt with an ongoing history of depression and anxiety. It is very personal, and was difficult to put before the public. When I showed the work together, many people were disturbed or disconcerted. A few women were offended by the sexual imagery in its objectification. Of course it is the artist’s job to challenge, and I was always open to friendly dialogue with detractors, whose time would have been better spent being offended by so-called “women’s” magazines like Cosmopolitan, with their inflexible ideals of femininity (e.g. “Get a perfect butt!” or “10 ways to blow his mind in bed!”), than by my own sexual grapplings. But these experiences have been helpful in understanding my work’s impact on people, and have allowed me to continue pushing boundaries as I become comfortable with the medium.

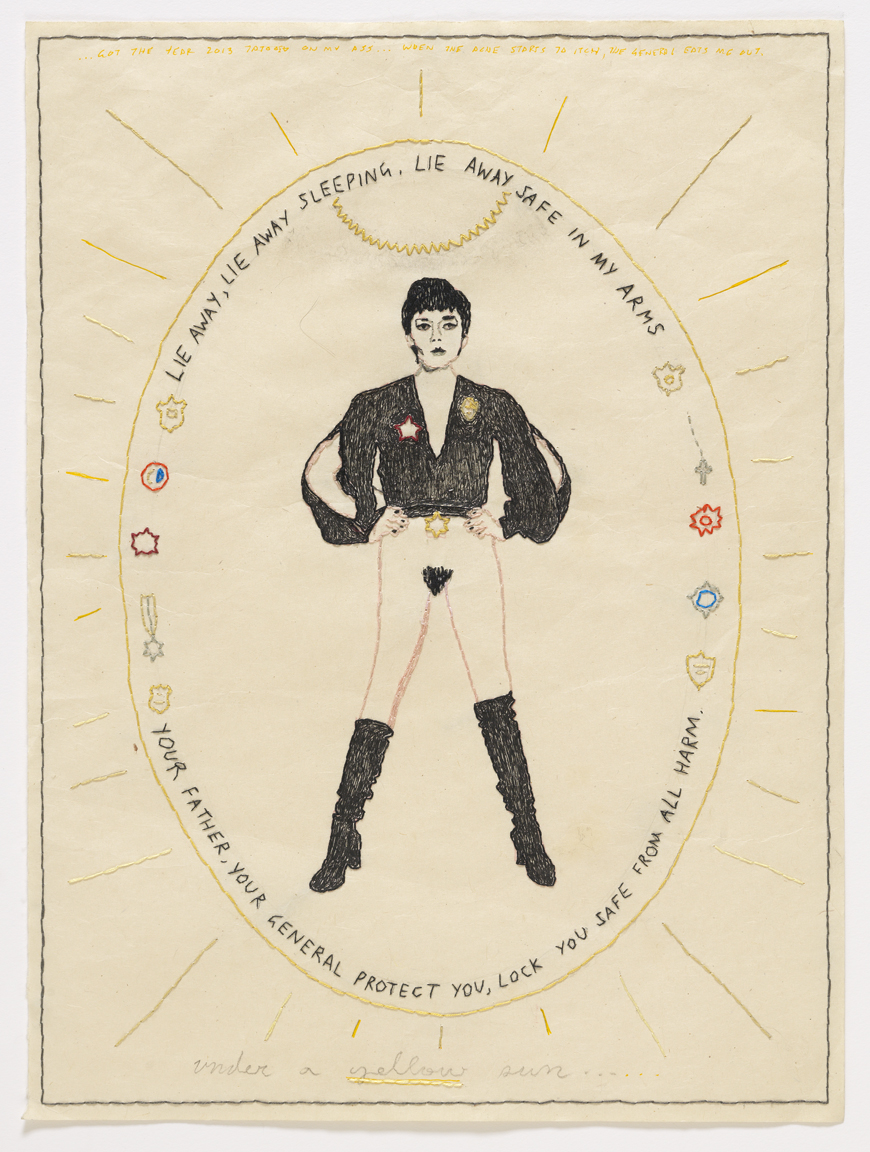

The new series, The Glittering World, further draws upon themes of women and sexuality, not as they pertain to men on a sexual level, but as they exist (or should exist) in a sexist society that objectifies women. I try to turn this prejudice on its head in depictions of female super heroes and villains who I show as both powerful and vulnerable in their sexuality, particularly in their (some would say bizarre) partial nudity. There is a fetishization to all of this, dating back to a childhood fear of and attraction to tough girls and women. This is perhaps best exemplified in the piece Under a Yellow Sun (Ursa), which depicts the villainess from Superman II, an object of childhood fear, fascination, and attraction, now appearing at once threatening and pantless.

Aside from exorcising childhood fears and fantasies, I also trace these images to more recent influences, particularly Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1915 feminist novel Herland and it’s many intentional and unintentional offshoots and imitations (such as the female-populated island of Olympus in the Wonder Woman comics), and most recently such pop culture icons as She-Hulk and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. I enjoy watching tough women, whether it is a 70s rape-revenge exploitation film or an epic fantasy television show about a young woman “penetrating” male vampires with wooden stakes.

What are or were some of the strongest currents from your influences you had to absorb before you understood your own work? The artists who have influenced me produced work that fearlessly exposes their inner lives. It took some personal crises of my own over the past few years to make me utterly comfortable with treating my work like a diary or confession, putting anything down on the paper I felt I needed to in order to truly bare my heart or soul, or whatever you want to call it. Then of course the next hurtle was mustering up the courage to show it. But at the end of the day, we’re artists, and how many of us pass up an opportunity to show? Nevertheless, it was initially quite nerve wracking.

Do formal concerns, such as perspective and art history, interest you? I think many formal concerns become second nature to an extent, and most of the “foundation” rules and theories I have either fully absorbed to the extent that I don’t think about them, or have been gradually, and happily, unlearning them. As to art history, it is still extremely important to me, and I am always looking to the masters, less for direct inspiration for my own work than to see the myriad of ways artists have attempted to put their own “issues” on display.

What do your choice of images mean to you? As I mentioned, the imagery is so personal that it takes a lot of initial deliberation on my part before setting it to paper. They are very personal but hopefully universal as well: knives, razors and other objects of (self) harm; sexual imagery (e.g. a preoccupation with women’s asses); medications (antidepressants, anti-anxiety meds and painkillers); pantless heroines…

Do you look at your work with an eye toward it like what can and can’t be visually quoted? In other words what you will or won’t cut out? With all due consideration to composition, I nevertheless try not to leave out anything that is pertinent to the emotion or sentiment of the piece. If I think of the work’s potential impact on the viewer I loose sight of the intent, nor can I worry about what can or can’t be visually quoted. If I did I would spend too much time deliberating and over-thinking, and that would come out in the piece. It is for these reasons that several pieces end up as failures.

Do you have any secrets in your work you will tell us? I have no secrets, period. When asked, “how did you do that?” I am always happy to explain, but I think it’s fairly straightforward. I am as a rule wary of artists who have “secrets”. They act as though they were the first to do something and the whole world is looking to rip them off. If someone rips off elements of my work and does it better, so much the better for them.

How do you hope history treats your work? A dangerous question. Of course I would like to see the work survive me, and hopefully find its place, however small, if not in the canon of art history than in the hearts and on the walls of those who have been affected by it.

Where can we find you and your work? I show intermittently with galleries in Boston and the Boston area but do not have a formal dealer. I also have several works in the flatfiles at Pierogi in New York. I can be contacted through my website, and hope that anyone reading this with questions or inquiries will feel free to contact me.

—–

eMbroidery was created with the support and wisdom of the magnificent Bascom Hogue.

If you are, or know of, a male embroiderer that we should interview as part of this series, contact us!