Welcome to Manbroidery, a series of interviews with male embroiderers. This month, John Paul Morabito.

Name: John Paul Morabito

Location: Chicago, IL

Main medium: Weaving, durational performance, and video

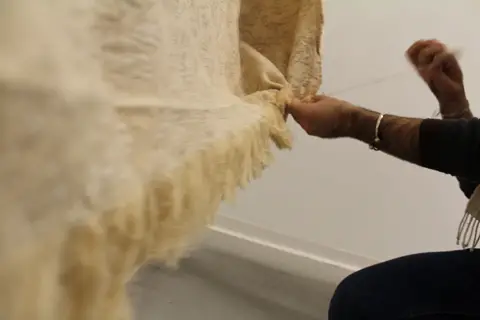

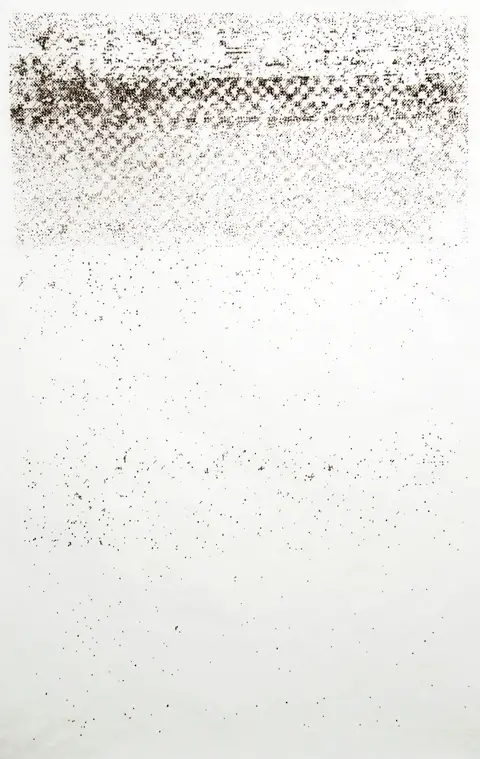

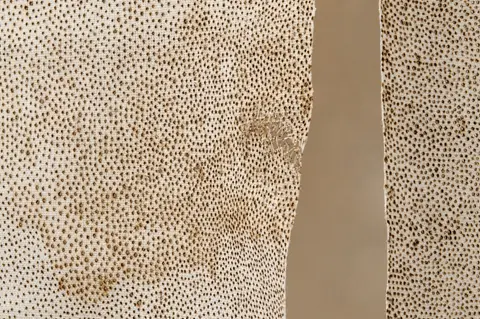

Noteworthy projects or pieces: Over the course of three years I worked on a series of hand woven and repeatedly burned textiles. My work has since taken on a new direction but the burned textiles laid the ground work in moving me toward a performance-based making practice.

How did you come to be a weaver?

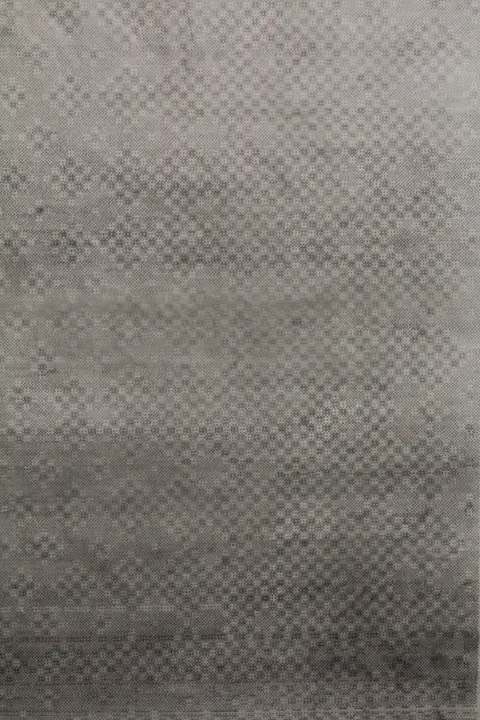

It’s just one of those things that never seems to go away. I really took to it when I first learned to weave (I was a total addict). At this point I think through a weaving “lens.” The binary logic of warp and weft and building line-by-line inform all aspects of my practice whether the work is textile related or not.

What does it mean to you?

I think weaving is really, really important to talk about. As a craft, at its’ basic level, weaving has not changed in thousands of years – warp and weft still interlace at right angle intersections. There is this powerful connection to history, but not just to the big history, to the bodily every day history throughout the ages.

Practically since its’ invention people have been wrapped in cloth from birth to death. There is very little in this world as ubiquitous as the woven textile and as such it talks so much about what it means to be human – all the good and all the bad.

As ancient a process as it is, weaving is still deeply relevant in our digital world. Not just as a means of production but as a means of discourse on the relationship of digital and analog.

Binary code is the language of the loom, so in a sense looms are early computers – the jacquard loom was a direct ancestor of the computer. This is a subject I can go on and on about so I’m going to stop there before I feed you a dissertation.

Where do you like to work?

I work almost exclusively in my studio. First of all, let me explain that I have a full wall of great big windows over looking downtown Chicago. It’s really nice to work and actually feel the passage of time as opposed to emerging from some cave not even knowing whether it’s day or night (been there done that).

When I was living in New York I had my studio in my apartment, something I will not be doing again. Separating the working space from the domestic space has been really important, I get more work done and when I’m at home I actually relax instead of just staring at the projects I need to work on!

How do people respond to you as a male weaver?

In all the time I’ve been working I’ve rarely come across the question. Historically weaving has been performed by both men and women and then there is its’ connection to the industrial revolution. Also I don’t tend to tackle issues of gender or queer identity in my work so my being a male weaver doesn’t come up much.

Who inspires you? Anni Albers, Agnes Martin, Kimsooja, Ann Hamilton, On Kawara, Magdalena Abakanowizc, Chiyoko Tanaka to name but a few.

I also have been blessed with some amazing mentors and teachers. I’m grateful to and inspired by Anne Wilson, Christy Matson, Annet Couwenberg, Piper Shepard, Susie Brandt, Christine Tarkowski, and Karen Reimer. They’re all amazing artists who have been so innovative in the field.

How or where did you learn you learn how to weave?

I learned to weave way back in high school. One of my art teachers, Barbara Allen, was a weaver herself and brought in small table looms for us to work with. It’s been an integral part of my life ever since and I’m really grateful to her for introducing me to it.

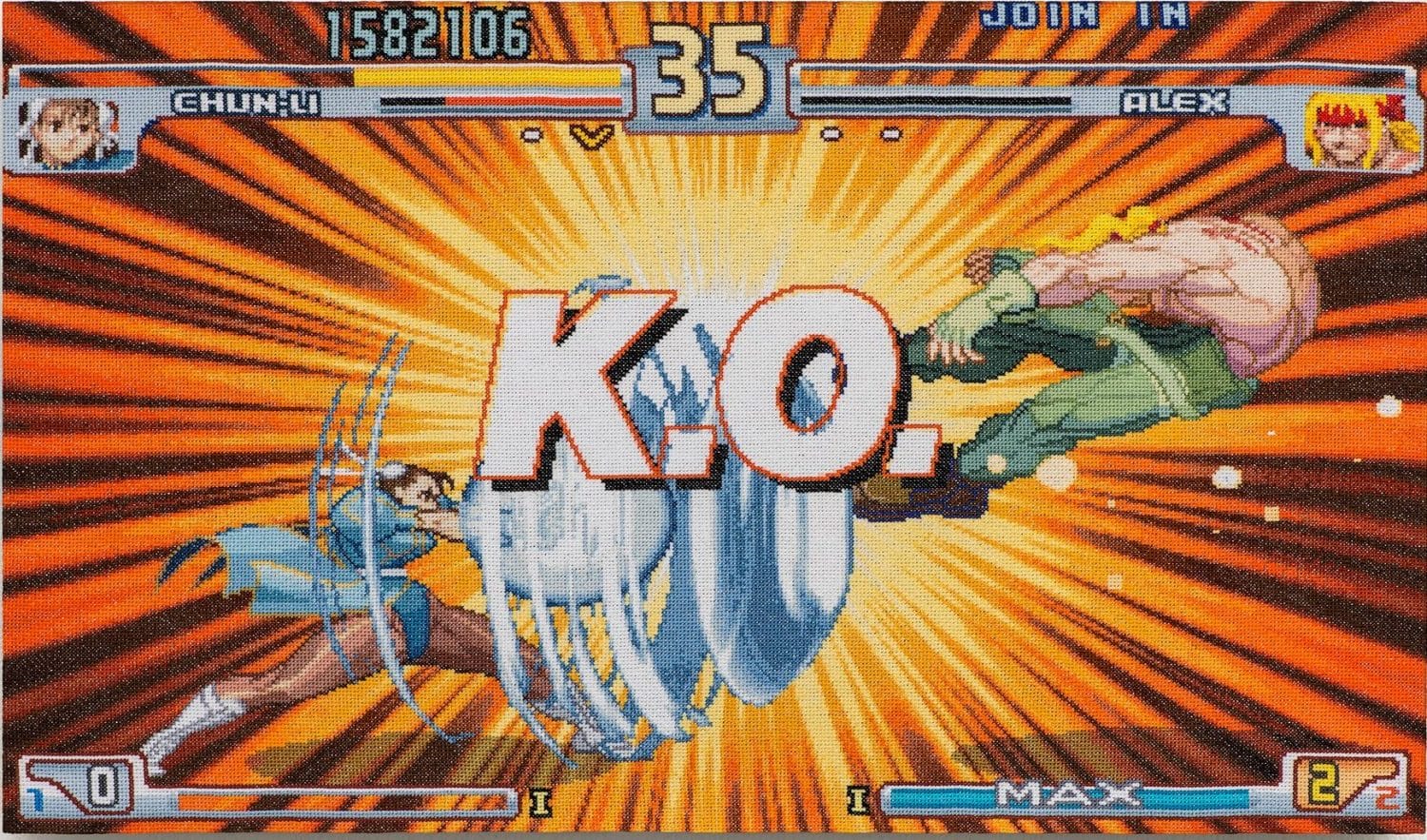

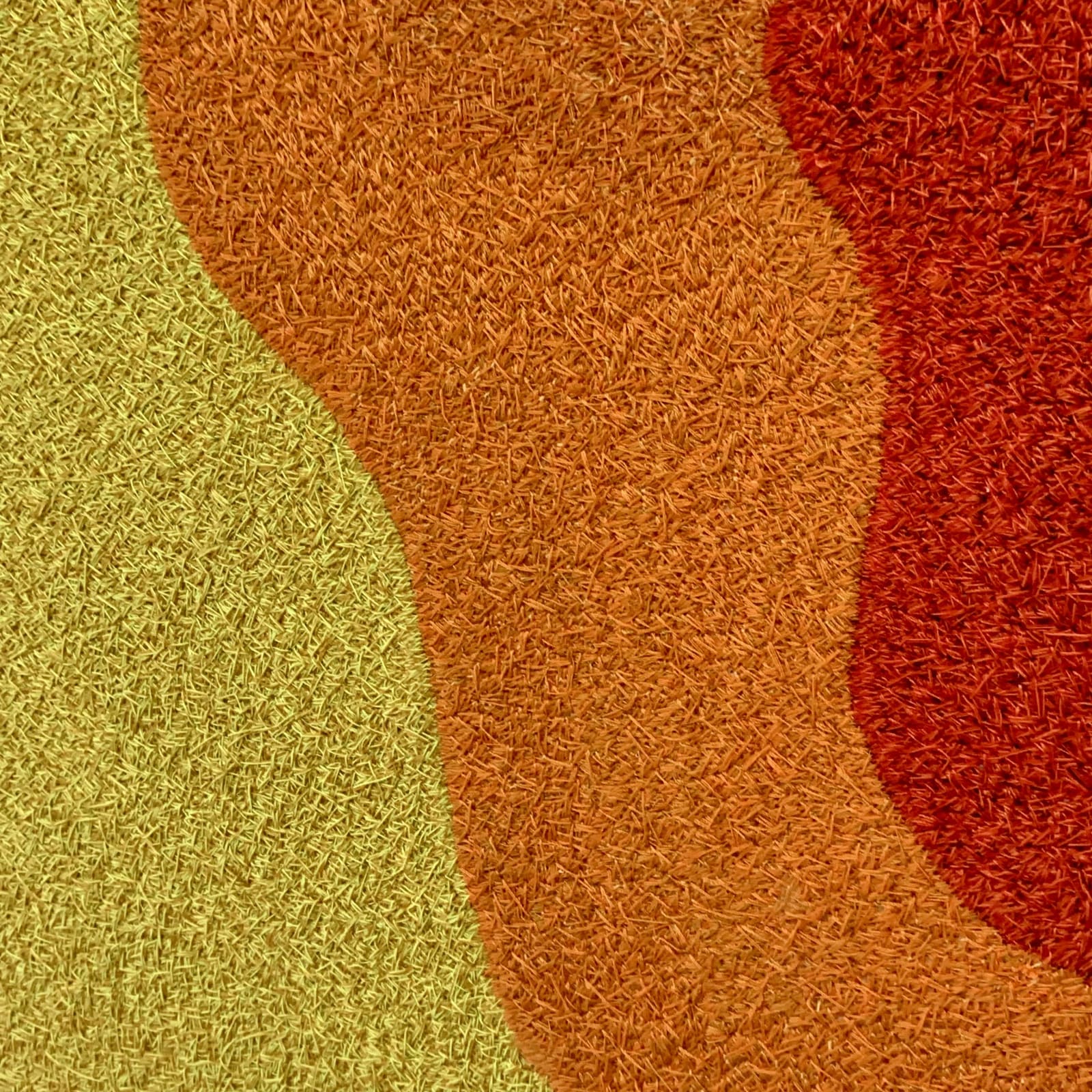

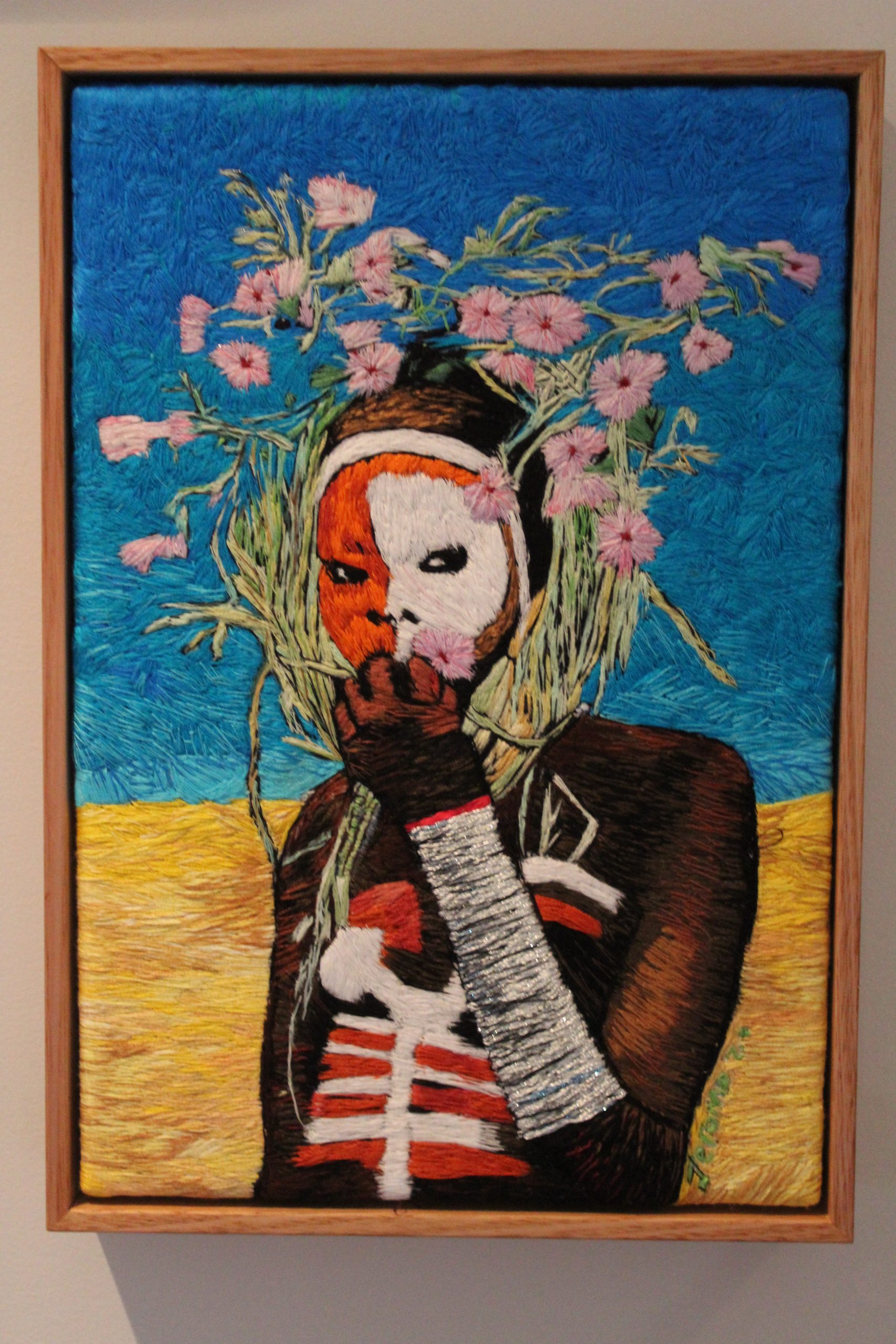

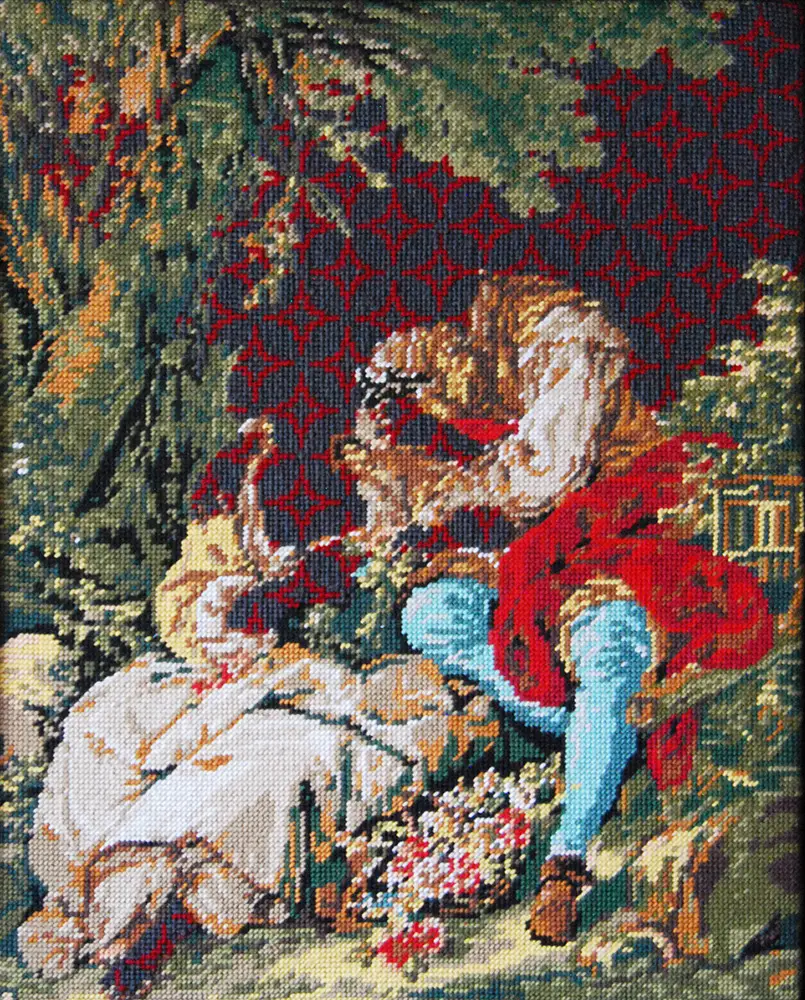

Are your current images new ones or have you used them before?

Well it’s a smattering of newer and older works, kind of a mix of what I’ve been showing for the past few years and a few newer ideas.

How has your life shaped or influenced your work?

I spent a number of years working as a designer in the textile industry and that time has deeply affected not only the type of work I make, but many of the strategies I employ behind the scenes. My work engages questions of somatic and mechanic labor, questions that I may not have asked had I not spent time in the textile industry.

What are or were some of the strongest currents from your influences you had to absorb before you understood your own work?

I was raised Catholic and it took me a long time to accept that it strongly influences my work. The dogma isn’t there but the work is most definitely born out of the Catholic imagination. Ideas of incarnality and bodily, masochistic penance as devotion or meditation run heavily through my work. I think it’s always been there in some fashion or another.

Do formal concerns, such as perspective and art history, interest you?

Most definitely. I think for a work to truly function criticality and formalism have to work together. As to art history, I think that’s very, very important. Artists, in some way, are always having a conversation with the past.

As a weaver I most definitely look to the International Art Fabric movement of the 60’s and 70’s – it’s something of a secret history but I don’t think we’d be talking about textiles as art without it. I also look to 1970’s masochistic performance art. It started a conversation about the body in art that I find to be really important to my own practice. And if you move forward a couple of decades you come to the late 90’s and artists like Ann Hamilton and Janine Antoni.

When I was first training they were presented to me (and a lot of artists around my age) and we were constantly talking about there work. Their use of performance and materiality I think has been hugely influential in my work and that of a lot of my peers.

What do your choice of images mean to you?

Images… Well I derive whatever images I use from processes. It’s much more about the means than the ends for me. Process dictates form and therefore content.

How do you hope history treats your work?

Bit of a loaded question, huh? I hope that the work is looked at as interdisciplinary art that critically engages craft – i.e. engages methods of production, ubiquitous materiality, the relationship of the hand and the machine in both material and cultural production. Currently there is a lot of work being made that uses craft methodologies as conceptual tools. Terms like “Critical Craft” are being thrown around a lot. Perhaps it’s a movement. I’d like to be remembered as a contributor to it.

Where can we find you and your work?

Currently I live and work in Chicago. I’ve got a few shows slated for the coming months. I’ll have some work up in “From Lausanne to Beijing” the Chinese fiber biennial which opens in November. I’ll also be showing video of a durational performance at the Lexington Art League in a performance art exhibition called “Approach.” And once we get closer to the winter I’ll be doing a few exhibitions/performance events in Chicago – stay tuned for that.

Manbroidery was created with the support and wisdom of the magnificent Bascom Hogue.

Are you a manbroiderer with worthwhile work to share? Do you know a man who stitches and ought to be featured in this column?

Get in touch with us and we’ll and you to the growing ranks of marvellous manbroiderers!