In a slight diversion from our usual format, I’ve decided to creatively paraphrase one of the many questions from erstwhile embroiderers that I answer every week in the grand old tradition of what our host would call an ‘agony aunt’. Sadly, we have no such colorful colloquialism in the States, so for you folks, ‘advice column’ will have to do. Without further ado, here’s the first installment of ‘Ask the Ghost in the Embroidery Machine.”

Dear Ghost,

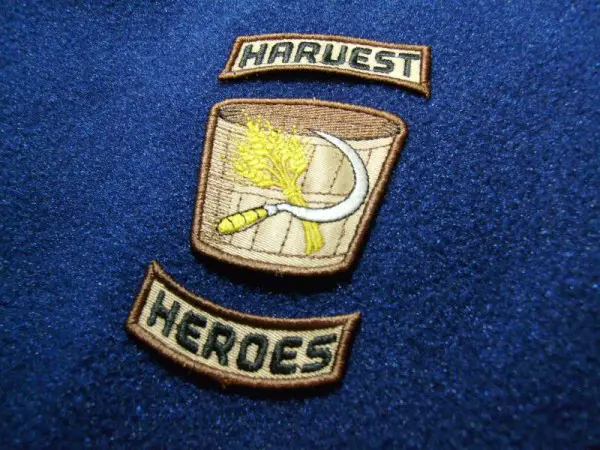

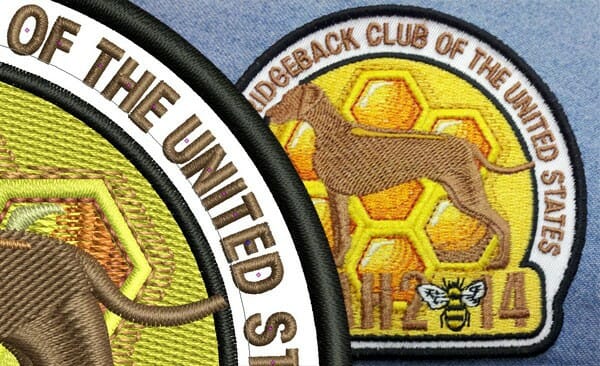

I work in a field where we are identified by our patches and badges- to pass the time I draw my own original patch designs ranging from simple setups to complex emblems, but I’ve never had the means to make my embroidery dreams a reality. If you were on a tight budget (as I definitely am) and wanted to start making machine embroidered patches (as I definitely do), what is the most economical way to make my own badges ? What machine should I buy?

Sincerely,

Puzzled by Patches

Dear Puzzled,

The first question I ask potential embroiderers intent on a specific project is something to this effect: Do you like embroidery well enough to spend hours engrossed in the technical ins and outs of the medium or do you just like patches? There’s nothing wrong with the latter, but if you are more a patch collector than an embroiderer, you may want to consider hiring someone to create patches for you before making an investment in time and equipment. Let me tempt you with the dark side of craft- commercial embroidery. If you want to make more than 50 pieces of a single design, numerous commercial houses will be happy to create patches from your original art. Local embroiderers may even create smaller numbers, contracting with a pro digitizer to create the stitch files. Small runs are more expensive per-piece, but not on the level of purchasing all you need to become an embroiderer. If you aren’t reconsidering your headlong dive into embroidery right now, you may just have the drive to do it yourself.

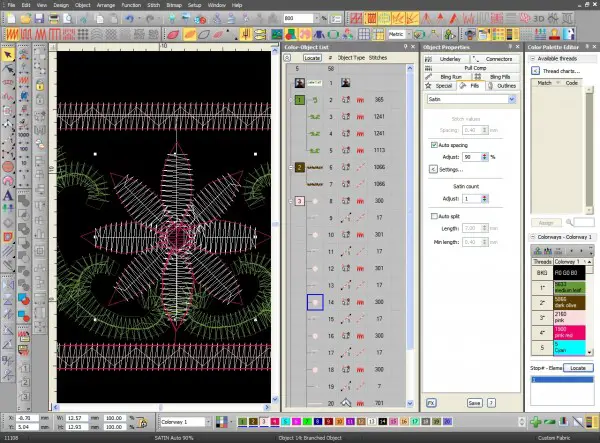

Once you’ve decided to take your first steps into home machine embroidery you may find that the machine isn’t necessarily the most difficult or the most expensive purchase. If you intend to become a one-person design and production team, not only will you need a capable enough machine and the correct supplies for the application, you’ll also need to purchase digitizing software. Moreover, learning to digitize embroidery designs is a fairly involved process that can be challenging and time-consuming, as capable digitizers need to know a great deal about embroidery to be effective. Not only must you learn to operate your software, you’ll need to know about the construction and behavior of fabrics, the application and properties of stabilizers, thread and other supplies, and the effects that sequence, speed, and tension settings can have on a final piece before you can create files that run reliably and with accuracy, let alone those that show any artistic ability in the interpretation from art to thread.

The best digitized designs will run similarly on any decently-made and maintained machine. Though machines are obviously crucial, they are only half of the process when custom work comes into play. That said it does take some consideration when buying your first hobbyist machine on a budget to avoid costly mistakes and eventual regret. Though commercial machines are excellent and the ‘prosumer’ multi-needle machines have commercial-like capabilities, for someone making emblems on a tiny budget, a simple single-needle machine will probably suffice. The cheapest versions are embroidery-only machines; this means that without a digitized file, they do nothing. No hand-guided embroidery, no construction stitching, nothing- they are paperweights without a file, so make sure that you are committed to automatic stitching before you buy.

The most common gripe among budget buyers is that the most inexpensive machines only have a 4” square embroidery area. This might sound large enough for any patch, but I implore you to go at least with the next larger size. I suggest a machine with at least a 5” by 7” embroidery field. It’s enough to get most patches embroidered with a little easement; shoulder patches like the ones worn by law enforcement professionals can get as large as 4” by 5”, so you’ll be needing those couple of inches. Entry-level machines are certainly not able to do all that commercial machines can, but even used, low-level multi-needles can be prohibitively expensive, running into several thousands of dollars even in the ‘prosumer’ range. You can get solid work out of a small machine, just keep your stitching light, maintain your machine properly, and be prepared to watch the machine as you run, particularly if you are stacking up the stitching or running on dense or difficult materials.

Next, you’ll have to decide what to do about digitizing. I love digitizing, so I’ll never discourage you from giving it a go- that said, it is an expensive hobby that will require a personal commitment if you are to become proficient. Remember; you don’t necessarily have to digitize, even if you choose to produce your patches yourself. You can always hire out the digitizing alone and embroider with the resulting file. A digitizer will gladly interpret your drawings for a fee, and it’s probably the easiest way to go from concept to finished piece in the beginning. Moreover, watching a good digitizer’s files run on your machine is an education into itself when you first learn to digitize, so there’s nothing wrong with getting a helping hand.

Should you decide that you want all the creative control, you’ll need digitizing software. Purchasing digitizing software can be a confusing process; to the untrained eye, the packages look similar despite wildly different price points. With numerous add-ons and options, it can incredibly difficult for new embroiderers to know just what they’ll need. Though I’ve always said that you can make any design imaginable if you can plot one stitch at a time, I can’t recommend fully manual work to most beginners. Good software will allow you to create areas and fill them with stitches in the basic stitch types and providing enough control to compensate for the natural distortion that happens with all embroidery. Though I’ve seen fairly capable software starting at roughly $300 US, my experience is that the least expensive packages don’t provide as many controls, may not have the most refined tools and may or may not have the best stitch placement when they fill an area. I don’t use non-commercial software with any regularity, so there may be more capable, inexpensive packages out of my ken, but I generally find myself eager to get back to my professional tools after I work with home software.

The commercial package I use is far more expensive, but with that expense comes fine grained control over variables and a wealth of tools that make the process quicker and easier; key considerations for someone who has to be efficient to make a living, but not as critical for someone who has the time to spend on doing things manually or refining their work. Luckily, even the good people who make my software are venturing into the home embroidery market with a slightly less capable, but entirely more affordable digitizing option starting in the realm of $1100 US rather than the thousands that the full commercial version costs- they even offer a 30 day trial for folks who want to kick the tires before going all-in. Make sure to consider the resources that surround your software before you purchase; check for adequate documentation and learning resources, the availability of official and user-run forums, and the possibility of one-on-one training. If you are incredibly lucky, you may find local hands-on classes at a sewing center that will allow you to take your first steps in both digitizing and embroidery without making a purchase beyond your class fees. In any case, strong support is important for both machines and software; don’t discount that when you make your choice.

Patches and badges are a great deal of fun to create, and you don’t need to risk ruining a finished garment to make them. I, for one, have had a great deal of fun creating patches both for myself and for my day-job as a commercial digitizer and designer- they are one of my favorite ways to employ embroidery (even if my friends in wardrobe don’t give me much lead time to get them stitched.) Whether or not you end up stitching them yourself or becoming a digitizer in your quest for the perfect patch, I hope that you and my readers give patch-making some sincere consideration.

—–

![]() Erich Campbell is an award-winning machine embroidery digitizer and designer and a decorated apparel industry expert, frequently contributing articles and interviews to embroidery industry magazines such as Printwear, Stitches, and Wearable as well as a host of blogs, social media groups, and other industry resources.

Erich Campbell is an award-winning machine embroidery digitizer and designer and a decorated apparel industry expert, frequently contributing articles and interviews to embroidery industry magazines such as Printwear, Stitches, and Wearable as well as a host of blogs, social media groups, and other industry resources.

Erich is an evangelist for the craft, a stitch-obsessed embroidery believer, and firmly holds to constant, lifelong learning and the free exchange of technique and experience through conversations with his fellow embroiderers. A small collection of his original stock designs can be found at The Only Stitch