Welcome to eMbroidery, a series of interviews with male embroiderers. This month, Theo Humphries.

Name:

Theo Humphries

Location:

I live in Bristol, in England, but I’m a full-time lecturer in Cardiff School of Art & Design which is in Wales.

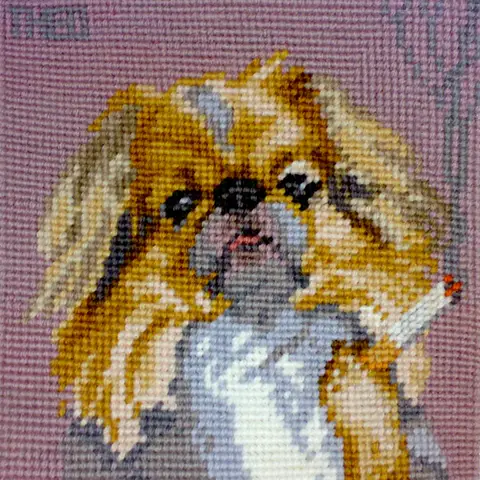

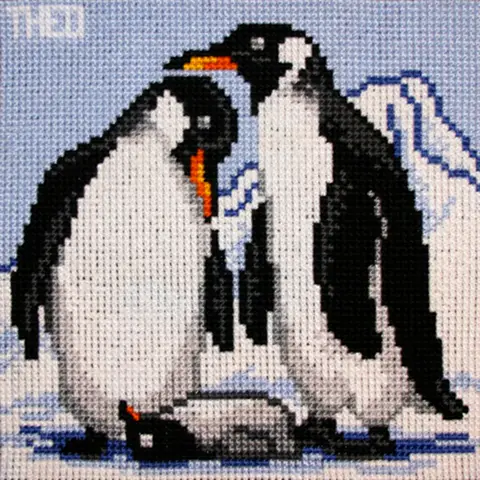

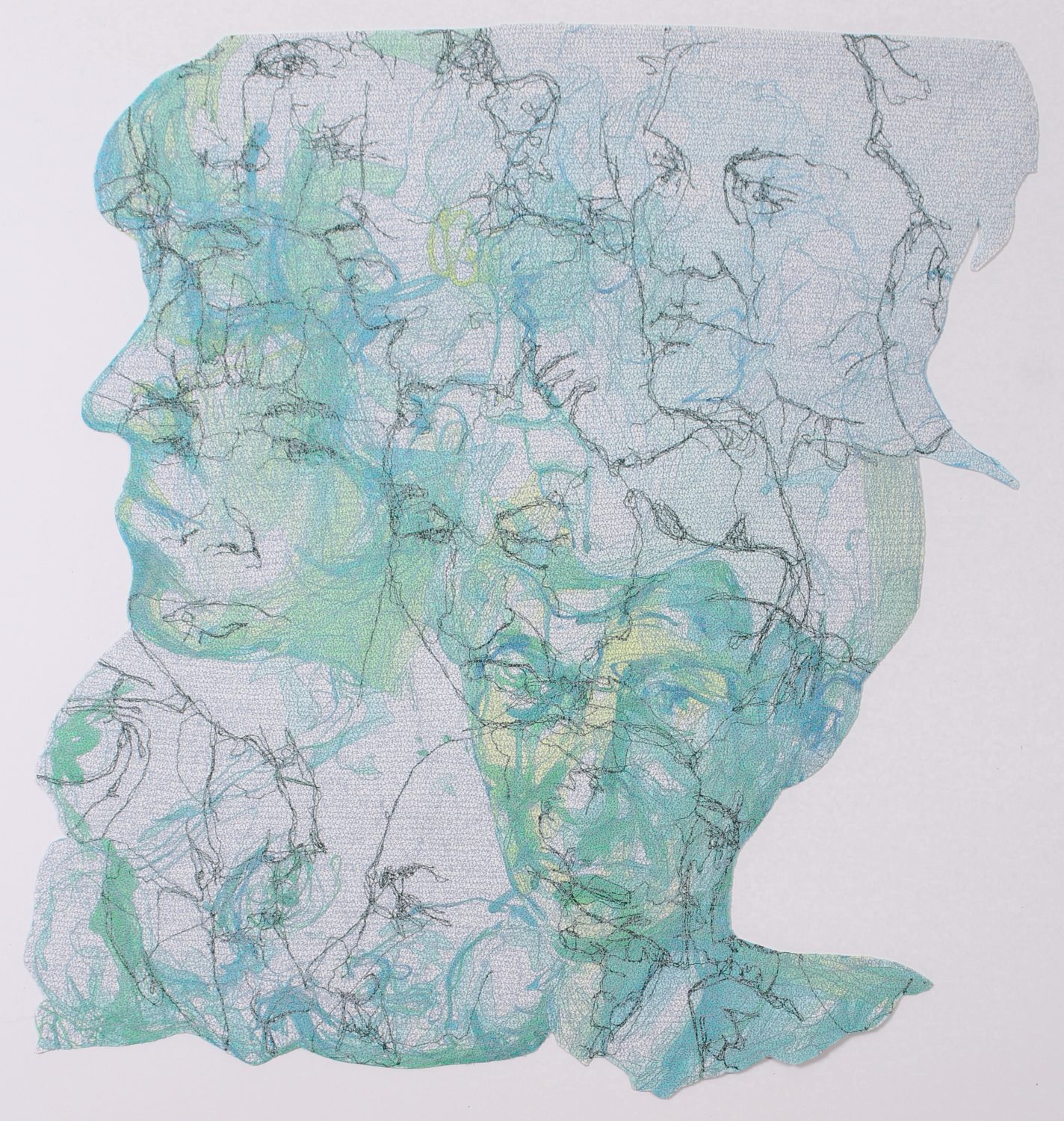

I work exclusively through the appropriation of commercial cross-stitch kits; modifying the original designs to create new images. I’m interested in shifting meaning, criticality, incongruity, and pixel art; hopefully it’ll make sense when you see them.

Noteworthy projects or pieces:

As the cliché goes, my favourite piece is the piece that I’ve just finished. However, I do have some personal favourites: ‘Ducklings’ from the ‘Food’ collection, because it just so inexplicable; and my pair of nude Kingfishers, because of their charming characters. I’m also very fond of the ‘Japanese Spaniel’ from the ‘Smoking Dogs’ collection, it was one of the first kits that I completed back in 2006 and I’m very happy with the way that it seems to capture the momentary spasm of the smoker’s cough.

I’m working on a project called ‘Leaves’, which will be a composition of six or more kits that, when viewed together, depict a fresh corpse hastily covered by autumn leaves. It will take years to finish, but when it’s finally complete I think it’ll be my crowning cross-stitch.

How did you come to be an embroiderer?

In 2006 I was fortunate enough to visit an exhibition entitled ARS 06 “Sense of the Real” at Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, in Helsinki. It was a brilliant exhibition and featured work by Kent Henricksen from his ‘Timeless Pleasures’ series. Henricksen took canvas tapestries that appeared to be quite old, and stitched ‘googly’ eyes and pointed hats onto the embroidered characters. I immediately connected with this work, and was inspired to create some augmented tapestries of my own.

I began looking around for tapestries online, just to see what was out there. It was only when I realised that I could buy crapestry kits that I had the idea of changing the designs.

Some time later I reached a critical mass of works and set up crapestry.co.uk (a playfully obvious contraction of the words crap and Tapestry) to share them. I have been adding to my collections ever since. My crapestry began as a frivolity, but now I take it rather seriously.

What does it mean to you?

My crapestry is very important to me, but it is only one aspect of a busy life. I wish I had more time to stitch, but then I wish I had more money, never had to work or sleep, and would live forever.

Where do you like to work?

I rework the commercial designs on my laptop, which is usually within reaching distance, so this happens anywhere: on the train, in bed, etc. I photograph the original printed canvases and then develop new designs in Photoshop using coloured dots. This is the more cerebral stage of the process as reworking the design requires a conscious effort. There are a multiplicity of possible ‘stixel’ (stitched pixel) configurations to consider, and working at effectively very low resolutions has its own set of associated problems. I experiment a lot.

The next stages are rather different in that they’re more mechanistic. Once I’m pleased with the digital design I translate it to the canvas; repainting the design by hand with acrylics (see my website for a more exhaustive explanation).

The next stage is the stitching. I usually work in our living room, in the quiet moments of the evening, and during lazy weekends or holidays. My job is rather intellectually demanding; one reason that I cross-stitch is because I can get ‘lost’ in it, in the autonomic process of stitching. Whereas some embroiderers are ‘creating’ as the stitch, possibly freehand, possibly without a grid, I’m doing something else, I’m just realising the design that I created previously. I find it relaxing; I’m resolving a material problem with my hands, rather than an intellectual one. Time passes in stitches rather than minutes. I hope that makes sense – I think it will to fellow stitchers. Tranquility pursued through craft.

Finally I make stretch frames for my works, in my studio, in order that they can be exhibited and sold.

How do people respond to you as a male embroiderer?

Very positively. Some people are initially quite surprised, which is fair enough (I’m a big guy, with a big beard, and a shaved head – not the stereotypical embroiderer). This is especially apparent if I’m stitching in public. But when people see the subject matter it quickly makes sense to them. People think it’s funny, but funny ha ha, rather than funny weird!

Who inspires you?

One answer might be: people involved in critical art, especially those employing appropriation, e.g. Emily Stoneking (aKNITomy) and her knitted vivisection subjects, Knitta’s craftism, Banksy’s pieces such as ‘Show Me The Monet’ and his ‘Crude Oils’ works.

But the more important answer might be that I suppose I’m most inspired by Vervaco, the company that produces most of the kits that I ‘hack’. Without Vervaco and contemporary companies churning out their particular style of mainstream, affirmative kits I might not be cross-stitching at all! I’ve previously described such designs as “superficial chintz; spectacularly vapid, vividly dull, unquestioningly conformist, and gaudily bourgeois”, but the truth is that their commercial success gives my work meaning.

I occasionally consider how they might react my work, and whether they know about me (my work often appears alongside theirs in Google searches). Maybe one day I’ll ask them.

How or where did you learn you learn how to stitch or sew?

I’m self-taught. I’ve learnt to handle the yarn, but also to deal with the design issues – manipulating the designs and translating them to canvas. As far as the material process goes; I began simply by reading the instructions on the back of a kit, everything after that was purely experiential. I learnt to judge the shear tension of the wool, spinning the needle in my fingers every few stitches to maintain a pleasing rope-like twist (a technique I recommend to all cross-stitchers), and to approach the stitching of complex patterns strategically, and methodically, so that the stitches present even crosses.

How has your life shaped or influenced your work?

It’s more that my work has influenced my life. In all honesty, the first kit that I bought was for a laugh, I just wanted to make something funny. Now, nearly 40 pieces, and incalculable hours later, I still have plenty of ideas and enthusiasm, so crapestry will continue to distract me from other pursuits. When I attempted my first piece I didn’t expect to get so addicted to stitching. Like other junkies; I find it hard to resist the constant temptation of the needle.

What are or were some of the strongest currents from your influences you had to absorb before you understood your own work?

I’m a part-time PhD student, my research involving the study of humour, and of design. I often find myself applying critical and philosophical theory to my crapestries; Kant and Bergson’s concepts of incongruity, Clarke’s ‘Pattern Recognition Theory of Humour’, Freud’s ideas of ‘release’, Classical Greek notions of the weaponisation of humour, etc., etc., etc.

As is often said that: ‘humour is a complex subject’, and I often consider this complexity. ‘What’s funny about a dead penguin chick, or a thermonuclear attack? (see ‘Penguins’ from the Guerrillas in the Misc.’ collection, or ‘Sunset Barn’ from the ‘War’ collection). That’s a complex question. To bastardise McLuhan: I guess the humour is in the medium – it’s funny because it’s cross-stitch. I find that fascinating.

Do formal concerns, such as perspective and art history, interest you?

Yes, very much so. Many of the pieces that I produce pay homage to artefacts from the history of art, for example the Venusian characteristics of ‘I am Woman’ from the ‘Kingfishers’ diptych.

What do your choice of images mean to you?

Absolutely everything. When I began cross-stitching, several people suggested that I should just create my own designs. But this entirely misses the point of what I’m trying to do. I try to preserve as much of the original image as I can. The history of the image is important to me, the original must be ‘present’ for my interventions to make sense, and to be meaningful, funny, or both. The mass production, and mass success, of commercial kits legitimises my unique versions.

Do you have any secrets in your work you will tell us?

Not secrets in the traditional sense, but there are stories that aren’t told on the website; for example, in order to create a piece that I’ve recently finished that depicts a lynching (‘Elephant’ from the ‘War’ collection) I needed to outline a baying mob in silhouette. In order to do that I traced a photograph of people queuing for a cash machine, and duplicated them repeatedly. Some people might read significance into the selection of this source material, some might not.

How do you hope history treats your work? This question made me smile! Other projects that I have been involved in were intended to have an impact that reaches across time, but this isn’t a major concern for my crapestries. I’m not being dismissive, or overly modest, but my crapestries are highly personal; they’re for me, not for ‘history’. If my aim for this project was to create works of historical significance then I don’t think that cross-stitch would be the medium that I’d choose. I hope, of course, to be proved wrong!

In the intended spirit of my crapestries; I would also hope not to be taken too seriously. I often write texts, blog entries, and exhibitions plaques that intentionally employ language that could be misconstrued, as of course could my crapestries themselves. My intention is to toy with the boundaries that separate the serious from the silly, the critique from the pontification, the profound from the superficial; I’m doing it now. Or am I? Yes! And of course, no.

When I say of the female kingfisher crapestry that “the luxurious foliage of her exotic pubic plumage is demurely obscurant and yet brazenly explicit in the same moment” the attempt is to be coterminously meaningful, immature, critical and facetious. Some of the text above is written in this vein.

Where can we find you and your work?

Most of my pieces are available to view, and to purchase, at my website: crapestry.co.uk

—

eMbroidery was created with the support and wisdom of the magnificent Bascom Hogue.