Our good host asked that I begin this adventure with a bit of ‘Digitizing 101’, and I am all too happy to oblige, though I will be covering some philosophical ground along with the technical realities of the craft.

Embroidery digitizing is the process of creating files containing commands to drive the movement of an embroidery machine’s hoop and needles. These files will convert art into embroidery for apparel embellishment, patch making or decorative repair.

The process of digitizing, however, is somewhat more complicated. Digitizers interpret an image into stitches through a variety of methods, using any one of a multitude of software and hardware combinations. They may do so a single stitch at a time or by drawing shapes that they then fill with stitches set programmatically to their own cocktail of variables delineating stitch length, type, angle and density. Beyond this technical definition, however, lies something nearer to the truth.

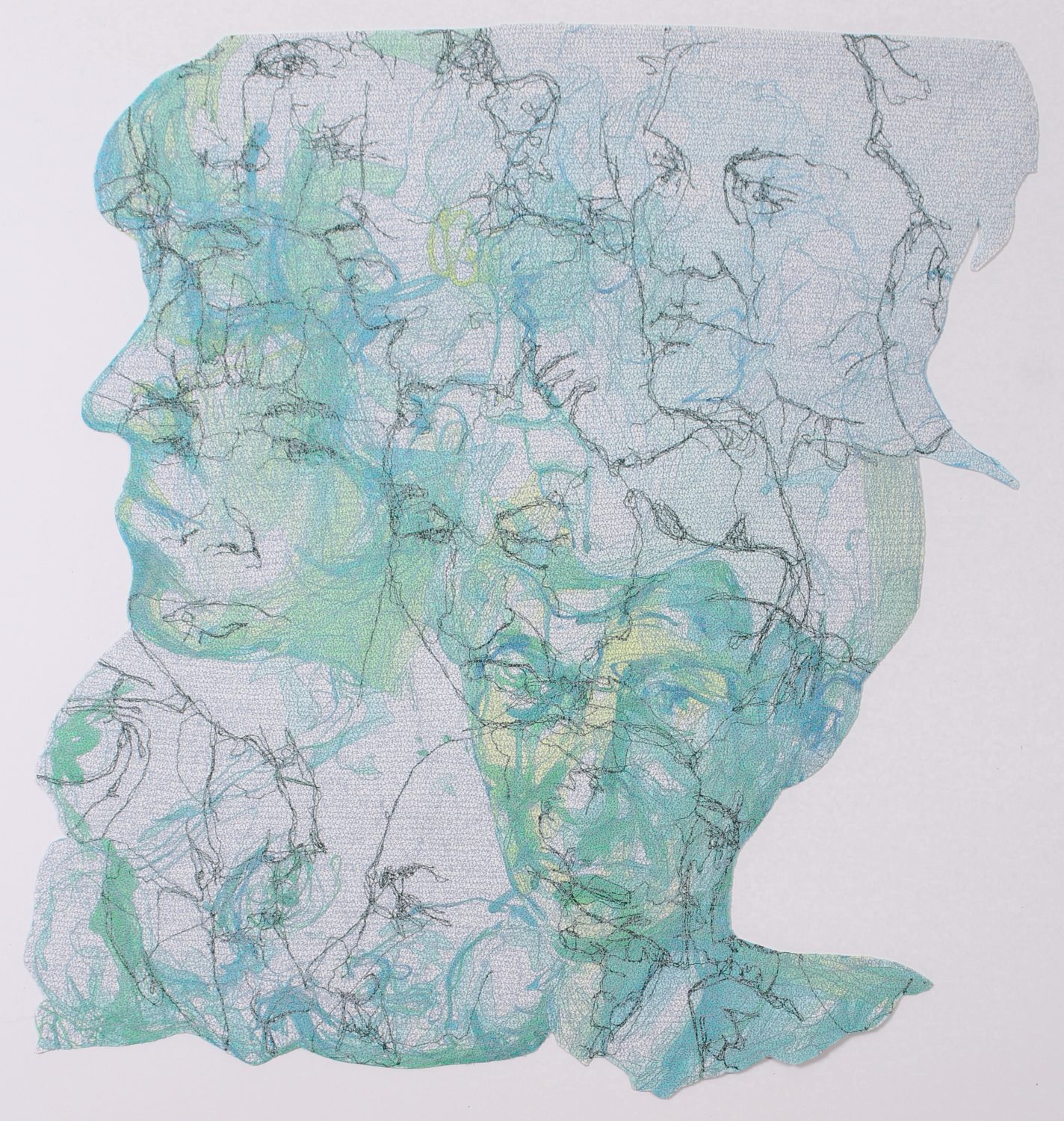

Embroidery digitizing, at its best, combines a measure of scientific curiosity and a technical mindset with purposeful, artistic interpretation, taking into account the unique properties of thread and fabric as media. I know my definition may be cold comfort to those looking for a way to ‘convert’ a graphic file automatically into embroidery- but though software manufacturers have done their best to make it possible, the most expensive and well-crafted software packages I’ve used have never been able to make the technical and artistic decisions as well as even a dedicated amateur digitizer.

If you are looking for a software-driven solution, my description of the art will likely disappoint. If, however, you are a focused, creative, and curious individual with a little of the scientist blended into your artistic persona and are willing to embark on a journey to control the powerful artistic tool that is your embroidery machine, you will be rewarded with the keys to unlock a world of expression. If this is you, by all means, let’s begin.

What do we mean by the ‘science’ and ‘art’ of digitizing?

Many novice digitizers think that learning software tools will make them immediately capable of producing fine embroidery, but they have only grasped the last and least important piece of the puzzle. It is only in knowing the technical nature of the craft and by cultivating an eye for artistic interpretation that they will reach their potential as digitizers. This technical nature is what I refer to as the ‘science’ of machine embroidery.

This is more than just technical knowledge; like proper science, this also describes a technique- a method of testing, as part of this understanding. Testing that leads to the ability to create reproducible, predictable outcomes in their embroidery. As for knowledge, a digitizer should possess a solid understanding of the process as a whole.

The functions of embroidery machines, the way that thread and needle interact with fabric and stabilizers, the way that stitches interact with each other, the natural levels of distortion caused by the tension of the thread, the stretch of the material in question, and the movement of the machine. Though this can be taught, the testing method of this ‘science’ of digitizing yields experience that bolsters this knowledge.

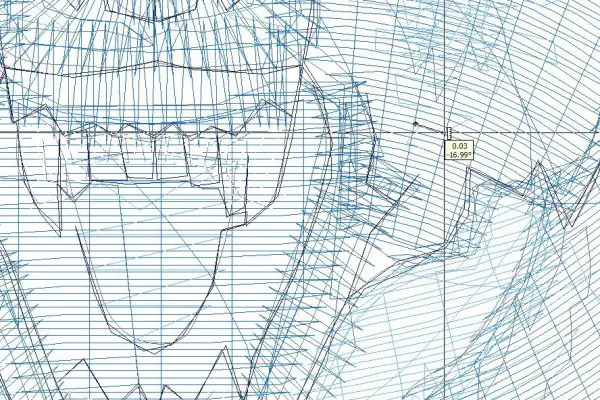

The best digitizers get their start by running machines. In watching designs stitch, the reactions and interactions of the media are readily seen. A well-crafted design can even teach proper construction, sequencing of the stitched elements, and compensation for the natural stresses of the process. Adding measurement to that observation completes the method, unlocking the secrets of digitizers and allowing us to test and refine our own technique.

Using ruler tools in software to measure the stitch parameters of designs we love allows us to apply these parameters to our own work. We can also physically measure the difference between our stitched samples and the on-screen dimensions used to create them to observe and correct the inevitable distortion. In carefully testing our designs on their intended fabrics and with the recommended supplies and measuring our results, we can readily see the results of our efforts and measure the effects of anything we alter.

By combining the analyzed settings of other digitizers with our own tests, we learn how long stitches should be, how much elements should overlap so that they don’t pull apart when stitched, how narrow satin stitches run on particular substrates, and how close together stitches must be to cover a surface. Experimentation and measurement can teach us a world of information and let us peek into and remix the techniques of our favorite design creators. Even so, the science alone can’t produce truly great embroidery.

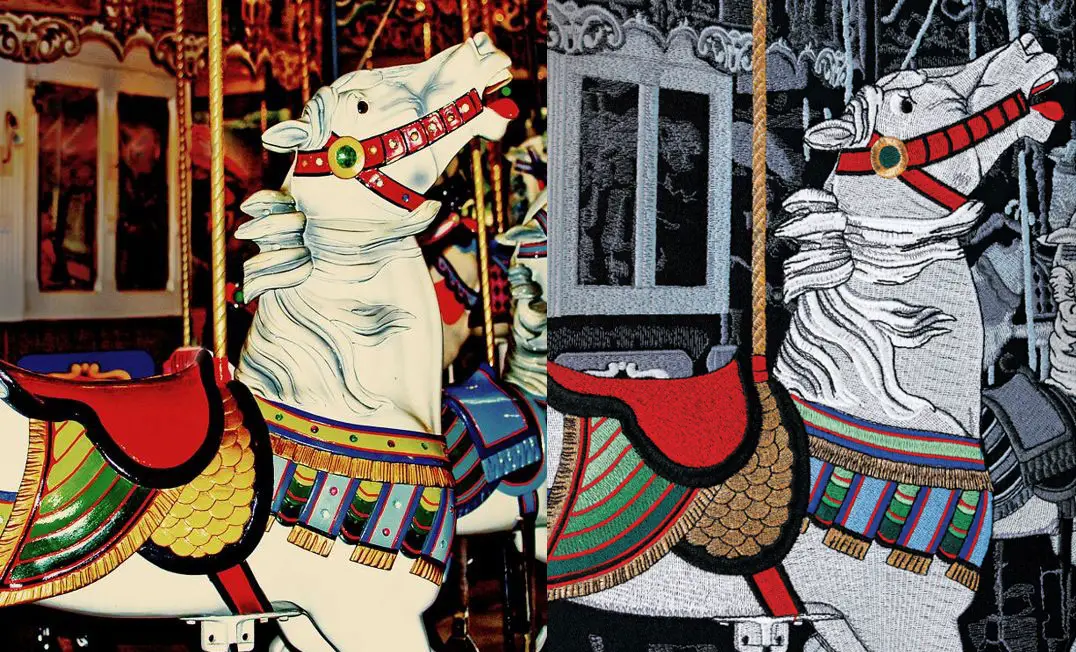

The ‘art’ of embroidery digitizing, while it has roots in the ‘science’, takes a more subjective turn. This is where auto-conversion fails and digitizers, with their understanding of the way light plays on the surface of thread and who can use the nature of this very physical and three dimensional craft take over.

The ‘art’ comes from appreciating the qualities of thread and textiles and using those to create textural, sculpted interpretations of images rather than attempting to simply render them like a ‘thread printer’. We learn ‘art’ by analysis, but not in the technical method previously described. We learn by looking at embroidery and attempting to think in its terms. We look at images and imagine them in thread, creating dimension, light and shadow with the qualities we have observed in stitches- mentally framing and carving cylindrical volumes in satins, filling large plains in tatami fills, tracing fine lines with straight-stitch runs.

When we absorb this nature of embroidery we start to see how stitch angle and density alter the perceived color of thread; that the play of light over stitches set in a certain direction can give a sense of grain and texture that shows volume in a shape and that our choices let us command a world of qualities with which we can represent the objects in our images.

These qualities become the palette with which a digitizer paints. The digitizer uses different stitch types not to simply fill areas, but to convey qualities of a subject and add to an image through textural and dimensional development. This is why an artistic digitizer outstrips the auto-conversion software; software can’t draw what isn’t immediately visible in an image, nor readily ignore what is. The digitizer can give an impression of elements too small to render, choosing what to leave out, or can add elements or qualities that aren’t necessarily seen in the image- playing with texture, shape, and depth to create something more than the original, something crafted specifically for the medium and with an express knowledge of its qualities.

Embroidery digitizing, despite my somewhat complicated description, is not something mystical that can only be achieved by a gifted few. If you want to digitize, you can.

If the idea of spending hours practicing the art, or running samples and correcting for the mistakes in sequencing or fixing some element that has pulled out of registration doesn’t send you running for the hills, you’ve got more than a fair chance of making your way. The simple truth is that if you are willing to to build an understanding of what your machine and your medium can and can’t do, and to work with and against those boundaries, you are on your way.

Accept that the road to your masterpiece will be paved with failed samples, trial and error, and accidental thread breaks- give yourself the room to try, fail, and try again, and never forget to play with the qualities that intrigue you about thread. Do that, measure your results, and the rest will fall into place with practice. The tools and even to a degree the machine matter far less than understanding the glorious imperfection and controlled chaos of distortion that is machine embroidery.