I would find it hard to choose my favourite fabric. Silk comes pretty high. Linen is lovely. But wool wins. Wool is a super-fibre: natural, sustainable, breathable, fire-resistant, hydrophobic and fantastically warm. When I researched my book Sew Eco, I looked into the green credentials for wool, as well as other fibres. Wool scores pretty high for many eco criteria as it can be ethically and environmentally produced, although it troubles me that wool available in the UK is often shipped from Australia and New Zealand which is ridiculous considering England grew rich in the middle ages from its fantastic wool.

Wool is great for wearing, sleeping under, walking on and of course weaving, embroidering, knitting, sewing and pretty much everything else. Once upon a time, there wasn’t a great deal of choice. Wool was fundamental to the lives of medieval English people; clothing, bedding and, if wealthy enough, tapestries.

Churches were also made of wool, in that the wealth created by the English wool trade helped to build, decorate and support the finest Gothic churches in parts of medieval England.

England has the perfect climate to breed sheep and centuries of careful breeding produced particularly good quality wool from English sheep. The two main types of wool fibre produced were woollen & worsted (pronounced ‘woostid’), with worsted made from breeds of sheep that have very long coats. The long coats produce long lengths of wool known as the staple when the sheep is shorn, which when twisted together, creates a fine, smooth fibre of top quality, known as worsted. Shorted stapled wool is spun together and produces a more fluffy yarn, without the smoothness of worsted. Woollen fabric was usually fulled or felted to create a thick, heavy duty wool without the sheen of fine worsted.

The fulling process of woollens is fascinating: good quality woollen only was used as weak fibres would not withstand the process. The woven cloth is pounded by man power or mechanical fulling mills which you can see in action on the Tudor Monastery Farm BBC programme. The shrunken wool is then stretched on tenterhooks to dry before the final processing. The fluffy surface or nap is raised by brushing the wool with teasels then trimmed down with shears.

These processes created a fine, flexible, hard-wearing wool, similar in looks to felt, but based on a strong, woven cloth (whereas felt is made from matting the raw wool fibres together). Coats are often made with wool processed in a similar way today. You can compare coat-weight wool with wool blankets to see the difference: in blankets the weave is clearly visible but in a fulled cloth, the surface is fluffy and there is no sign of the warp and weft.

Wool has been grown, spun, woven, dyed and finished in parts of Britain continuously since the middle ages, although the industry has been in decline since the mid-Twentieth century. The combination of cheaper imported cloth and the availability of synthetics has caused the closure of the majority of wool production, although there are notable exceptions: worsted cloth (usually used for suits) and is still produced in England, particularly in Yorkshire and is a lovely fabric for garment-making. The tweed industry of Scotland, particularly the island of Harris is surviving and in some cases thriving, after a lean few years.

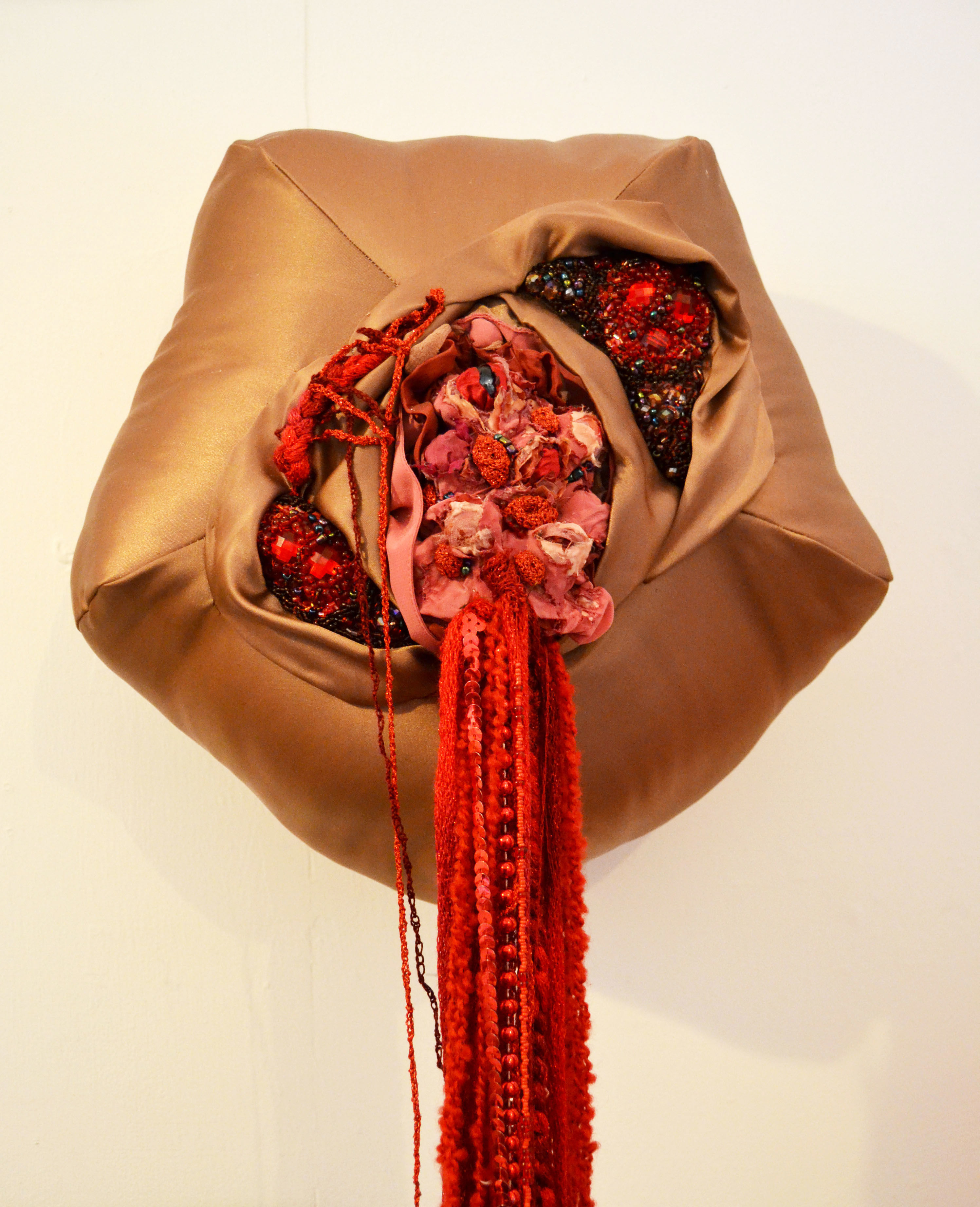

In the later middle ages and Tudor years, wool’s use in decorative interior textiles was mainly confined to tapestry, while silk was favoured for embroidery and the most luxurious woven fabrics, although some fine quality patterned wool cloth was made. Wool has been used for embroidery for a considerable period too, steadily growing in popularity in the Tudor & Stuart periods. Canvas work embroidery became popular for hangings and table carpets (luxury table coverings rather than floor cloths), and later for chair seats, often combined with silk threads for the finer details such as faces.

In the 18th century, a new style of embroidery became fashionable. Crewel work uses only wool threads, embroidered on a ground of linen fabric which remains visible between motifs, rather than the embroidery covering the whole cloth. Penny Nickels explored crewel on this site a few years ago.

The 19th century saw a massive growth in domestic, hobby needlework (as well as industrial and sweat-shop production) and the development of many new styles of embroidery. Berlin wool work sprang up in the 1820s after the innovation a Berlin couple who produced embroidery designs printed on squared paper, with colours added by hand in watercolour. The popularity of Berlin wool work continued until the 1870s, and has survived, in some way as so-called ‘Tapestry’ kits of pre-printed needlpoint designs.

In contemporary textiles using wool, crewel remains popular, with professional embroiderers like Tracy A Franklin producing some stunning traditional crewel work. Her blog even shows some pictures of the reverse which is always fascinating to see.

Katherine Shaughnessy’s book The New Crewel has helped bring wool embroidery back into fashion. Along with many other textile makers, I love recycled wool felt cloth made from shrunken jumpers or indeed coat wool, which is ideal for applique or quilting, and I also like to use by-the-metre wool felt for its wonderful non-fray, sturdy properties, while textile artist Alice Fox uses industrial wool felt to make vessels and embosses it using printing techniques.

I hope that this exploration of wool will encourage the use of wool cloth and thread by more embroiderers and textile artists. There isn’t a lot of commercial wool thread around, other than crewel and Tapestry wool, but I hope this will change soon so I can stitch with fine, high quality wool thread in the future. The combination of sustainability, receptiveness to natural dye and ease of use makes wool a really wonderful fibre to work with.