Somewhere in the maze that is Cairo’s market district, there’s a narrow lane winding between rows of tightly packed buildings, known as Khan Khayamiya, or Street of the Tentmakers. The narrow street is busy, noisy, and bustling with pedestrians, bicycles, small delivery trucks, and local residents going about their everyday business. Spilling out onto the sidewalks are rolls, heaps and bundles of multicoloured, richly designed tent panels, hand-stitched by the shopkeepers and tentmakers of this small Egyptian community.

Khayamiyas are the highly decorated canvas panels making up the roof and sides of traditional Egyptian tents. It originated in the Ottoman Empire but is now uniquely Egyptian. These panels are used as backdrops for weddings, funerals, concerts, and other public ceremonies. During the last few centuries, these panels were often collected by travellers and visitors to Egypt, including soldiers and foreign officials during the two world wars, and can now be found in museums worldwide.

Unfortunately, in recent times the market has become flooded with cheap, factory-printed, fake versions to replace the more expensive hand-made items at weddings and ceremonies. The tentmakers were forced to find a new market for their craft and adapted their designs to make smaller pieces for wall hangings, cushion covers and tablecloths aimed at the tourist market.

The irony is that even though khayamiyas are a traditional part of Egyptian culture, the tentmakers themselves get very little recognition from their own countrymen and women. In Egyptian culture, tentmakers are either unknown, regarded as tradesmen, or their work is being referred to as peasant work. Most of the acknowledgement they get as artists comes from tourists and foreign craftspeople who recognise their special talent as needleworkers, designers and artists.

It is through people like Jenny Bowker, an Australian master quilter, and Kim Beamish, an Australian filmmaker that their story has been told, and their art are being appreciated by a wider audience.

Making khayamiyas is a time consuming and labour intensive process. New designs always start on paper where a full-size square or circle is folded into quarters, eights or sixteens, depending on the complexity of the design. The tentmaker then draws with chalk on the top of the folded paper, working from the centre point of the paper outwards to create a segment of the design. It is important that all the lines touch the sides and folds to ensure that the design will be continuous when unfolded. Once he is happy with the design it is redrawn in pencil and pierced with a long thick needle. The piercing occurs at around 2mm intervals, following all the pencil lines.

Once the paper is unfolded it reveals a lace-like pattern which is then carefully smoothed down and pinned onto the background fabric. To copy the pattern onto the fabric the paper is sprinkled with talcum powder (for dark fabric) or charcoal (for light fabrics) and rubbed into all the piercings. The design is once again copied in pencil along the powdery dots before this marked layer of base fabric is tacked onto a canvas backing. At last, it is ready to be appliqued.

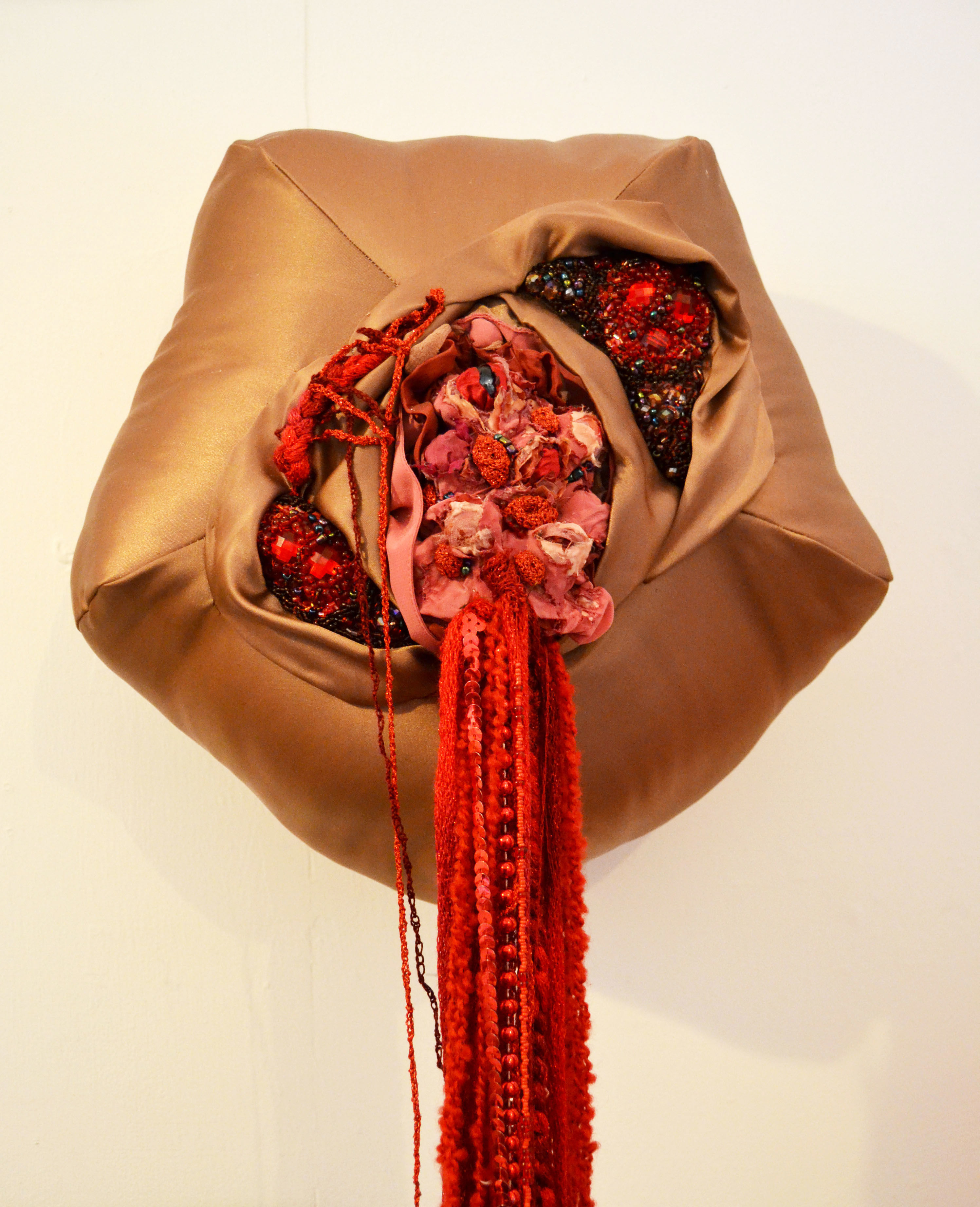

The applique pieces are cut, folded and stitched in one process. The tentmakers sit on the floor or on low benches with the tent panels folded around them and on their lap. Layers and colours are added one after another until a rich Tapestry of design, colour and pattern have come together to reveal an artwork. They sit in their shops, near the front door, ready to help customers, talking to passers-by and their fellow tentmakers in the shops next door or across the lane. Working, living and socialising all flows together in a continuous activity called… life.

*All photos courtesy of Jenny Bowker