Hello everybody! This week we’re going to be looking at the history of redwork embroidery. What does that mean? If you Google the term “redwork embroidery”, the top searches that pop up seem to contain the same information, nearly verbatim. It reads something like “Redwork originated in Europe in the late 1800’s and then traveled to the U.S. It became very popular due to the availability of Turkey Red dye which was colorfast and inexpensive.”

Well, okay. But that seems pretty, “Stuff Victorian People Like”, and if we’ve learned anything from exploring needlework traditions, surely that’s not the whole story. Does redwork mean pictures? Patterns? Screw it, we’ll look at both. Let’s get in our Wayback/Carmen Sandiego Machine!

When we looked at the history of shisha and mirror work, we found that they tended to be used in a ritual capacity. Well, not surprisingly, red stitches are typically used the same way. How do we know? In regions where needlework traditions are largely unchanged, they are still used for the same purpose. We are likely to find red stitches used on seams, hems, organ areas, head coverings, as well as clothing and accessories used to mark a transition or aid in rituals.

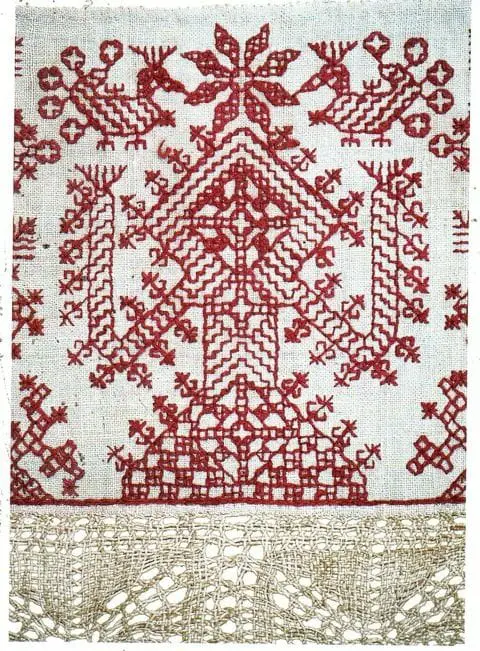

A wonderful example of this is the Rushnyk.

Rushnyk from my collection

The rushnyk is a ritual towel of Slavic origin used in wedding, baptism, and funerary rites, as well as ensuring fertility, and protecting the home and the inhabitants. Towel patterns vary depending on usage, but I’m fairly certain the one I’ve shown above is used for weddings. They tend to be made out of linen, and redwork is strongly favored. Notice the hooked lozenge/diamond pattern, which is a typical fertility symbol in textiles. (Click HERE for info on fertility symbols in textiles). According to The Ukrainian Village Project, “The ritual rushnyk is a very important item to which a great deal of power is ascribed.” It goes on to say, “The power of the rushnyk comes from the sacred act of embroidery.” Wiki also has an excellent article on these pieces.

Although we can’t be sure what the origin date of the practice is, we do know it was well before the 1800’s. But still, that’s not terribly old in the grand scheme. Let’s look at an example that is truly ancient.

This mummy, The Ice Maiden was found in 1993 by archeologist Natalia Polosmak. She was found in the Parzyrk Burials, which are a cluster of Iron Age tombs found in the Altai Mountains. She dates from the 5th century BCE and was given a ceremonial burial. She was found wearing a large headdress, a silk tunic, a full red skirt and felt stockings. Her costume is one of the oldest examples of fully preserved clothing from a nomadic society. Although it’s difficult to find information on the details of her clothing, we can look at other Parzyrk mummies for clues.

Detail of Ice Maiden’s clothing

A few linen shifts have been found in other Parzyrk burials that have couched red stitching along every seam, that widens into a red braid along the neck and wrists. We do know that the Ice Maiden also had braided thread details that were dyed red from insects. They have also found small needles in these burials that were used for embroidery and tattooing. Her headdress is also interesting, because similar garments are still worn in the region where she was found.

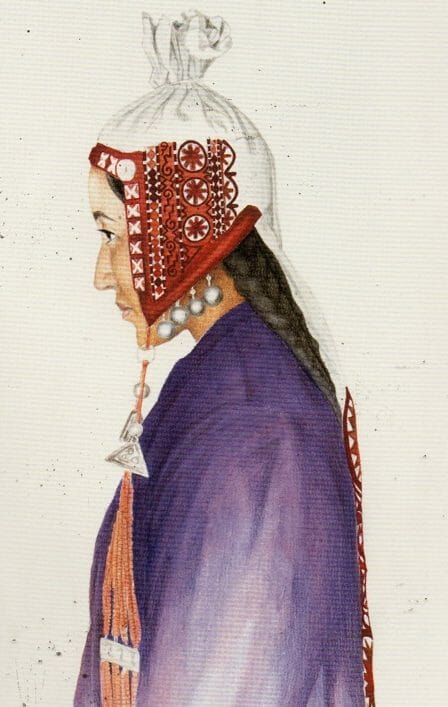

These illustrations show the traditional Chach Kep (bonnet and plait holder) and Ileki (Headdress/turban), worn by married women of southern Kyrgyzstan. These illustrations show costumes as they were worn in the late 19th century. Apparently, they are still worn in some regions, but infrequently in others. I’ve included both drawings so we can see how the headdress fits over the bonnet, and we can see the redwork along the face opening. (Remember what we learned about embroidered openings?) Also, notice the redwork over the plait holder. Two long braids signify marriage. Traditional patterns indicate status, occupation and membership within a family. After setting the marriage date, the young lady would prepare her trousseau. This would include creating felted and embroidered pieces that would decorate the yurt, bedding, quilts, privacy screens, ect. Apparently, she would be careful not to use any knots in her needlework for fear of “knotting” the potency of her husband. According to the book Kyrgyzstan, headdresses were especially important because, “The head, sacred and through which passed the blessings of the gods, was thus specially encircled and protected.” (See notes)

This website offers an amazingly thorough explanation of the traditional clothing and regional styles. (Karakalpak Kiymeshek)

This handkerchief, embroidered with red silk thread shows the Coptic influence prevalent in Spain. Apparently in the village where this was made, Navalcan, labyrinth patterns are believed to have magical powers.

This ritual cloth from Tunisia depicts a goddess motif. Similar designs are quite common in agricultural areas that have long standing needlework traditions.

But hey! Redwork is supposed to be pictures! Well, I guess that depends on what sources we’re looking at. According to Needlework Through History: An Encyclopedia, the rise of blackwork in Spain in the early 1500’s also saw an introduction of those patterns rendered in red thread, which was referred to as “redwork”. And I haven’t even shown you my white cap stitched with red patterns from Sierra Leon! But okay. Whateves. Here we come full circle. In the late 1800’s, redwork traveled from Europe to the United States.

Dry good stores sold “Penny Squares”. Now, I’ve read different explanations of the name, that they cost a penny or depicted a penny, so I’m not sure. However, I do know that they were muslin squares that contained a basic design that could be easily stitched.

This redwork quilt from 1890 is a lovely example of these penny squares being out to work. It features six blocks containing embroidered animals, children, (some in national costume), and flowers. We can see the simple outline design that is common in traditional redwork from this period. This quilt contains a superstition square, although that practice’s authenticity has recently been called into question among Amish quilts.

This redwork quilt from 1890 is a lovely example of these penny squares being out to work. It features six blocks containing embroidered animals, children, (some in national costume), and flowers. We can see the simple outline design that is common in traditional redwork from this period. This quilt contains a superstition square, although that practice’s authenticity has recently been called into question among Amish quilts.

Okay. So why did I drag you guys all over the world and through time? I just feel like not looking at redwork from different periods and places is akin to declaring that the Easter Bunny lives in a burrow and doles out candy. End of story. It’s not the whole truth and doesn’t take into account the various points of origins and intentions.

__________

References and photographs for this article include-

- The Quilter’s Resource Book by Maggi McCormick Gordon (Quilt photos and info)

- Embroidered Textiles by Sheila Paine (Spanish/Coptic hankie and Goddess embroidered towel)

- Kyrgyzstan by Klavdiya Antipina (Illustrations by Temirbek Musakeev)

- As well as various websites that are linked and highlighted in the above text.