Welcome to Needle Exchange, where we talk about textiles and discover techniques and tips. Today we’ll be looking at Sashiko.

“Sashiko” means “little stabs”, the verb “sasu” means “to pierce”. This type of needlework is used in traditional Japanese quilting, and utilizes a long running stitch to form geometric patterns for reinforcement and embellishment.

It seems the earliest use of this method was to reinforce clothing to make them hard wearing as well as provide warmth by quilting. The earliest example is an 8th century monk’s robe, and then there’s not really records of the craft until the 17th century. However, this is what we do know. Sashiko seemed to be common among farming and fishing communities. It was never used as a commodity because the the clothing was largely pieced from older bits of clothing, sandwiched and stitched together.

As finer materials such as cotton or silk was unavailable to these communities, the fabric was usually made of hemp or ramie. Typically it was a balanced weave, the warp and weft being the same weight, and not too fine a thread count. A “thimble” is worn on the palm of the hand right below the middle finger in order to push the needle through the pleated fabric. This is also why having a less-fine weave is useful.

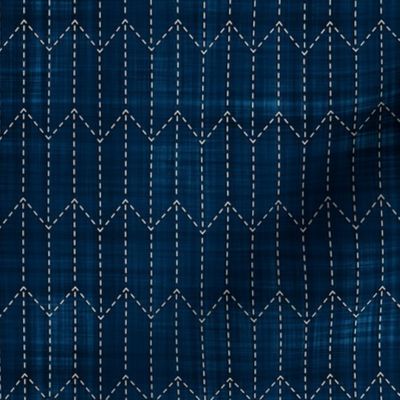

Although the stitches are counted, the fabric is not necessarily even weave. The deep blue color was produced by dying and over-dying in vats of indigo, usually the only dye readily available. White cotton thread was used for the stitching, although I’m not sure why cotton thread was available, info on that is spotty.

The geometric designs are useful for several reasons. The way the pattern is stitched guarantees very little waste, poor fabric is reused and reinforced, and the patterns themselves are talismanic. If we’ve learned anything from these articles, traditional needlework is almost always magical/spiritually significant.

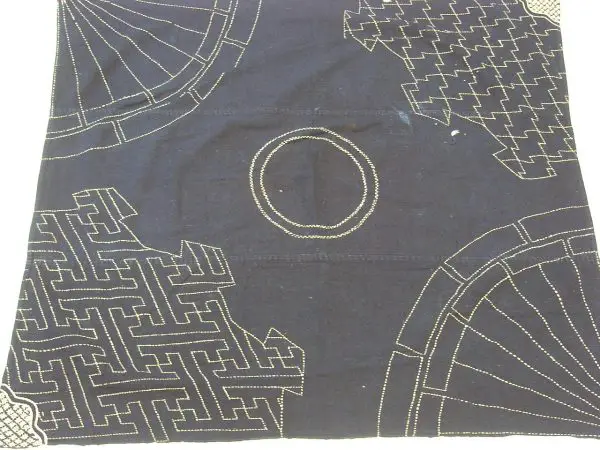

Examples of Sashiko Geometry include:

- Amimon – Fishing net, auspicious and promises a good catch.

- Yabane- Arrows, symbol of a warrior.

- Musubi kikko- connected tortoise shell, lucky number three with hexagons for longevity.

Here’s where we get serious. Like all needlework, there are regional variations. I’m not going to spend a ton of time on these and I’m not going to write about every style, but I hope I give you enough information as a jumping off point.

Tsugaru Sashiko

The Tsugaru peninsula is located on the northern end of Honshu island, Japan. It is traditionally one of the poorest and remotest regions of Japan, and experiences cool summers and heavy snowfall durring the winter. It is no surprise that we’d find Sashiko traditions there.

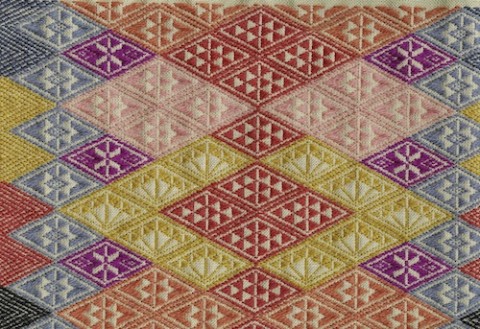

Tsugaro Sashiko employs “Kogin” stitching, a counted thread embroidery using a diamond shape as its main pattern. The indigo fabric must be an uneven weave, more warps than wefts, in order to work the elongated diamond.

Although this style was usually found only on kimono (robes rather than the fancy lady garments) and vests, now it is not uncommon to find it on screens, placemats, or other garments.

Nanbu Sashiko

Nanbu is located in the Aomori Prefecture on the northern end of Japan. Although the diamond motif is common with this work, the fabric it Is worked on tends to be a paler blue. It is called “hishizashi”.

Nanbu Sashiko is a counted stitch embroidery, but it is worked on even weave fabric unlike the “Kogin”. This style is also unusual in it’s use of colour. The thread is very bright, and it’s not unusual to see three or more colours used in a piece.

Now lets get to the fun stuff….

In the 18th century, Sashiko was also used as protective clothing for firemen. There were four groups of firefighters, and only the “machibikeshi”, the town people firemen, wore stitched garments. The uniform was stitches from the skin out- underwear, socks, leggings, pants, shirt, coat, gloves and hood.

When they would arrive at the fire, they would soak themselves in water which would protect them and keep them cool. The quilting allowed the fabric to stay saturated. When I was reading about fire fighting during the Edo period in Edo, (Wikipedia has a great article) I found this quote, “Fires and quarrels are the flowers of Edo“.

According to the article, “Even in the modern days, the old Edo was still remembered as the “City of Fires”. The city was something of a rarity in the world, as vast urban areas of Edo were repeatedly levelled by fire“. Yikes.

Then I read that a high number of the fires were caused by arson.

Wikipedia again: “Other than looting, frequent motives were those arising from social relationships, such as servants seeking vengeance upon their masters and grudges due to failed romantic relations. Also recorded were instances of merchants setting fire to competitors’ businesses and children playing with fire, and even a case with a confession of “suddenly felt like setting fire”. Since a fire would also mean business for carpenters, plasterworkers and steeplejacks in the subsequent reconstruction, some of them would delight at the occurrence and aggravation of fires. In particular, as many firefighters primarily worked as steeplejacks, some of them would intentionally spread fire for the sake of showing off firefighting skills in public or creating business opportunities for themselves. This prompted the shogunate to issue warning ordinances and execute some offending firefighters. Arrested arsonists were paraded through the streets before they were burned to death.”

Double yikes!! So what does this have to do with this article on sashiko? Only peripherally, but bear with me. I spent several hours looking trough Japanese woodcuts for examples of sashiko, which I barely found any. I guess I shouldn’t really be surprised because it was lower class clothing and maybe not fit for a study, but I did find common sashiko patterns in a few of the pieces.

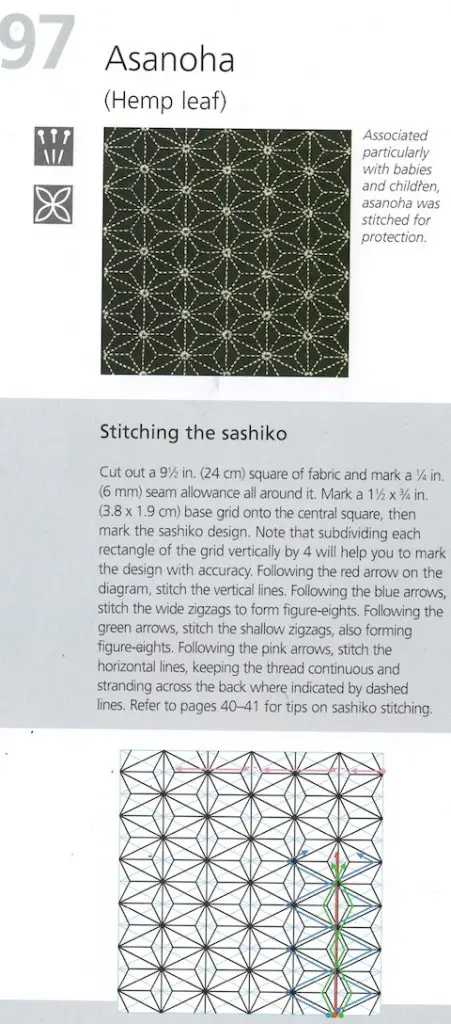

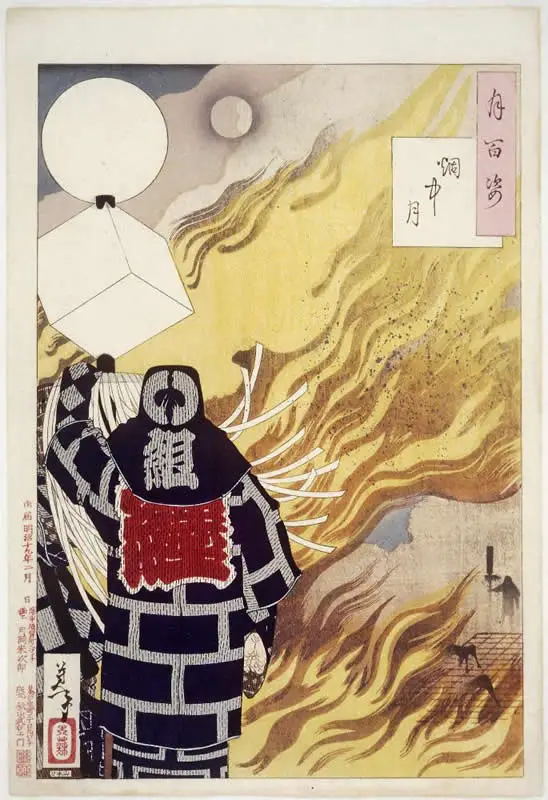

Like this one:

That light pattern on her kimono is called “Asanoha” or “hemp leaf”. According to my research, it is stitched for protection. When I looked up this piece, I found out that it is a portrait of Yaoya Oshichi. She lived in Edo at the beginning of the Edo period, and was the subject of many “joruri” plays, puppet shows.

From Wikipedia: “In December 1682, she fell in love with Ikuta Shōnosuke (or Saemon), a temple page, during the great fire in the Tenna Era, at Shōsen-in, the family temple (danna-dera). The next year she attempted arson, thinking she could meet him again if another fire occurred. She was caught by the police and burnt at the stake in Suzugamori for her crimes.” She was 16 years old. I’m pretty sure I saw a similar story line on Friends. Or maybe 30 Rock. BUT ANYWAY, Sashiko pattern, firemen… you see where I’m going with this. I’m lost.

Anyway, check out the links below for more on this technique. And now… A PATTERN!!!!

Related Questions:

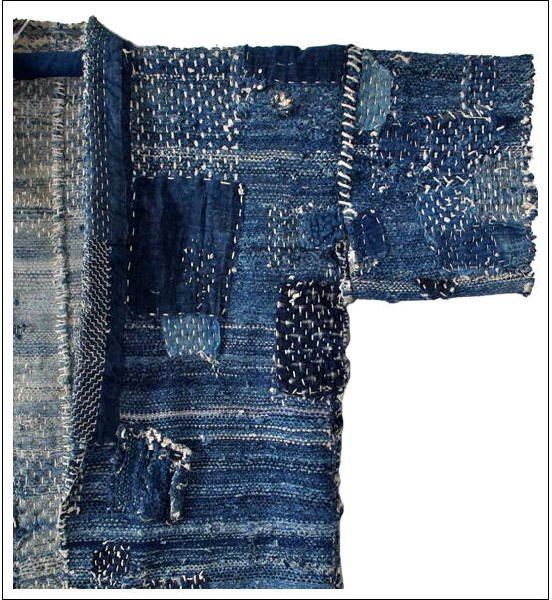

What is the difference between Sashiko and Boro?

Boro is a process of repairing or reusing fabrics, commonly with multiple repetitions of Sashiko. Sashiko is refers to the act of stitching onto the fabric, whereas Boro refers to the end result.

In the examples above you can see Boro in different forms, all of which have been embellished with Sashiko.

What kind of thread do you use for Sashiko?

Sashiko uses cotton thread that is made from multiple fine strands twisted into a single dense thread. This is different to embroidery thread, which generally consists of a few large strands, and means that the Sashiko stitches have a more robust appearance.

While you can do Sashiko stitches with “normal” embroidery thread, you will see the longer stitches appear to separate as the thread strands are not bound together in the same way.

What is Sashiko fabric?

The most common fabric used in Sashiko is cotton, which is often dyed with indigo. The open weave of the fabric allows the Sashiko thread to pass through with ease, enabling successful embellishment.

It is important to clarify that there is no specific Sashiko fabric, as Sashiko refers to the process of stitching and, as mentioned above, Boro are the fabric items produced using Sashiko.

Resources used in this article: