Welcome to Pinning The Past, where we explore textile techniques and traditions and connect with the rich history of embroidery.

Last month’s column on tapestry looked at who owned tapestries and why. This month we’ll be delving deeper into the making of tapestry. Did anyone do their homework and read The Lady and the Unicorn? It really does bring to life the world of Tapestry weavers and their relationships with the patrons who commissioned them. I’m going to cover some of the same ground, albeit in less refined prose and with absolutely no plot, but with more pictures.

Back to the very basics: What is Tapestry made of?

You’ll remember that is it woven, not stitched, so there is no base cloth to work on as in embroidery. With a weave, there are warp and weft threads making up the cloth. Tapestry is unusual in the woven textile sphere in that the warps are completely hidden by the wefts, rather than showing through as part of the finished weave. A strong, smooth thread is required and in the middle ages this was often worsted, a yarn made from long, lustrous wool fibres, spun in a particular way to create a robust, fine yarn which will not stretch or become fluffy in use.

The coloured yarns, used to create the designs, are usually wool, although some of the most luxurious medieval and Tudor tapestries included silk and even gold or silver thread for details. Later tapestries were woven entirely in silk too, but usually smaller scale than the great medieval hangings.

Colours and dyes

The wool threads used to weave the Tapestry were dyed in a wide range of colours and shades, but mostly only used a limited palette of dyestuffs. Variation in shades was vital to create light and shade, shaping and colour transitions, which require great weaving skills as well as the right coloured threads.

The root of the madder plant (Rubia Tinctoria) is used. It was imported into England from Asia.

The woad plant, Isatis Tinctoria.is a relative of Indigo, but one which grows in Britain, so was used here until stronger imported Indigo took over. The processed leaves produce the colour.

In combination, these dyes could produce purples, burgundy, greens, turquoise, dark browns and near-black.

Woad blue was usually over-dyed with yellow weld to create greens. Yellows often fade first, so historic tapestries of woodlands and greenery are often very blue. The back of the Tapestry, with the loose threads left from weaving, can often show us the original true colours of the Tapestry when new.

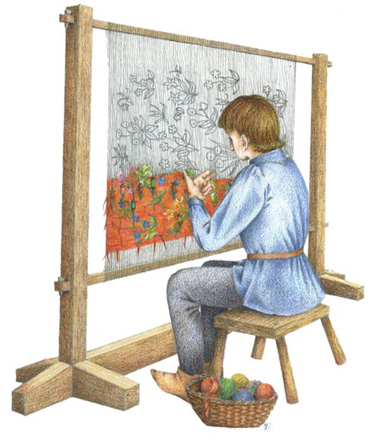

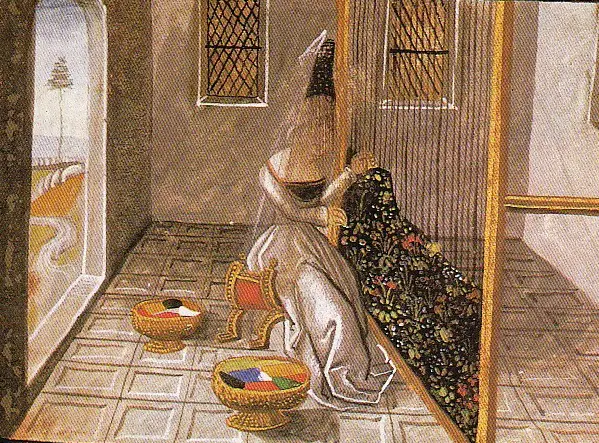

Unlike most cloth-weaving, Tapestry is generally woven on an upright loom, with the warp threads running top to bottom on the frame. For large tapestries, the loom has a cloth beam, where the finished weaving is wrapped around a pole, so the weaving can be moved along as it progresses.

Another construction technique peculiar to Tapestry is that it is effectively woven sideways – the warp threads will end up horizontal when the piece is finished. In addition, the weaver works from the back, looking through the warps to the design or cartoon, pinned to the wall behind the loom. As you can imagine, this presents some interesting challenges to the weaver who can’t actually see the Tapestry properly as they work. The reverse-side weaving is presumably why medieval tapestries sometimes have back-to-front text. The weaver draws working lines into the warp as they progress.

Small areas of the weave are worked on at a time, not across the full width of the loom as you would in normal weaving. The weaver uses a number of colours at a time, interweaving them on the warp threads to create shading, lines and definition in the design.

The finest Tapestry weavers of the middle ages were extremely skilled in creating colour transitions, shading and fine lines, all of which are difficult to do using this technique. These techniques though are what makes medieval and renaissance Tapestry so special – the colours, the shading, the depth, the accuracy of line and the incredible detail added up to create wall hangings that stunned their viewers.

Where was it made?

The majority of tapestries produced in the later middle ages were woven in the Low Countries – North East mainland Europe near the coast, comprising of parts of modern Belgium, France, The Netherlands and Germany. Weavers were skilled artisans, generally employed in small workshops lead by a master weaver. Apprentices and journeyman (paid by the day weavers) assisted the master weaver and would have created much of the Tapestry as well as taking care of the preparation – winding wool and preparing warps. The master would most likely have taken charge of the most challenging parts of a design such as faces. Officially, all weavers were men, but as in all artisan crafts, the master’s family would also have been involved, including wives and daughters. Sometimes widows or unmarried daughters took on the trade of a husband or father and ran their own businesses.

Who created the designs?

Artists created the original drawings or paintings which would be reproduced in Tapestry. Specialist draughtsmen were responsible for creating the cartoons, sometimes creating their own designs, but usually following an existing print, drawing or painting. In the vast majority of cases, tapestries were commissioned and those paying for them would have had firm ideas about what they wanted. The draughtsmen’s skill came in translating a print into a full-scale cartoon which could be yards wide, whereas the weavers skill came in adding colour, texture and life to the line drawing.

The techniques of Tapestry weaving haven’t changed greatly since then and skilled weavers still use the same techniques now. In the same tradition, Dovecot Studios trains and employs Tapestry weavers to create commissions for clients, and has done since 1912.

Artist weavers both design and make their own Tapestry. I first came across artist-made Tapestry at the V&A, where in 2004-5, Sue Lawty was Artist in Residence where she showed the influence of the natural landscape on her work.

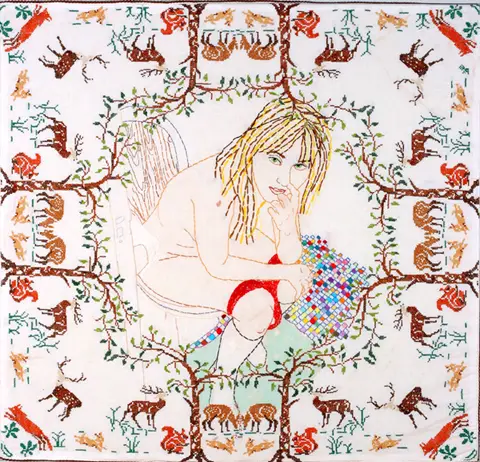

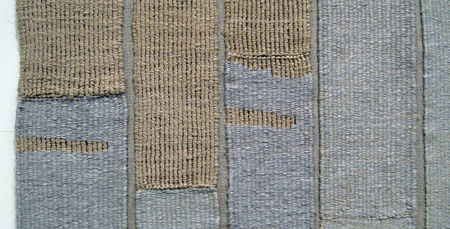

Many other contemporary Tapestry artists take inspiration from the natural world including Hillu Liebelt who created this series Winter Sun.

Jilly Edwards looks towards fields and fences in her recent work.

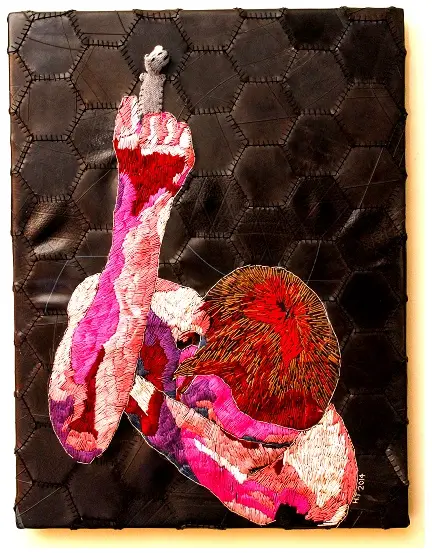

Fiona Rutherford takes a more abstract approach, using chunks and flashes of colour in her long, thin Tapestry pieces.

—–