When President Macron of France offered to loan the Bayeux Tapestry to Britain it reminded me of the 19th century embroiderers of Leek, Staffordshire who embroidered a complete facsimile of the tapestry. Strictly speaking both the original and the copy are embroideries and not tapestries; coloured wools stitched onto linen.

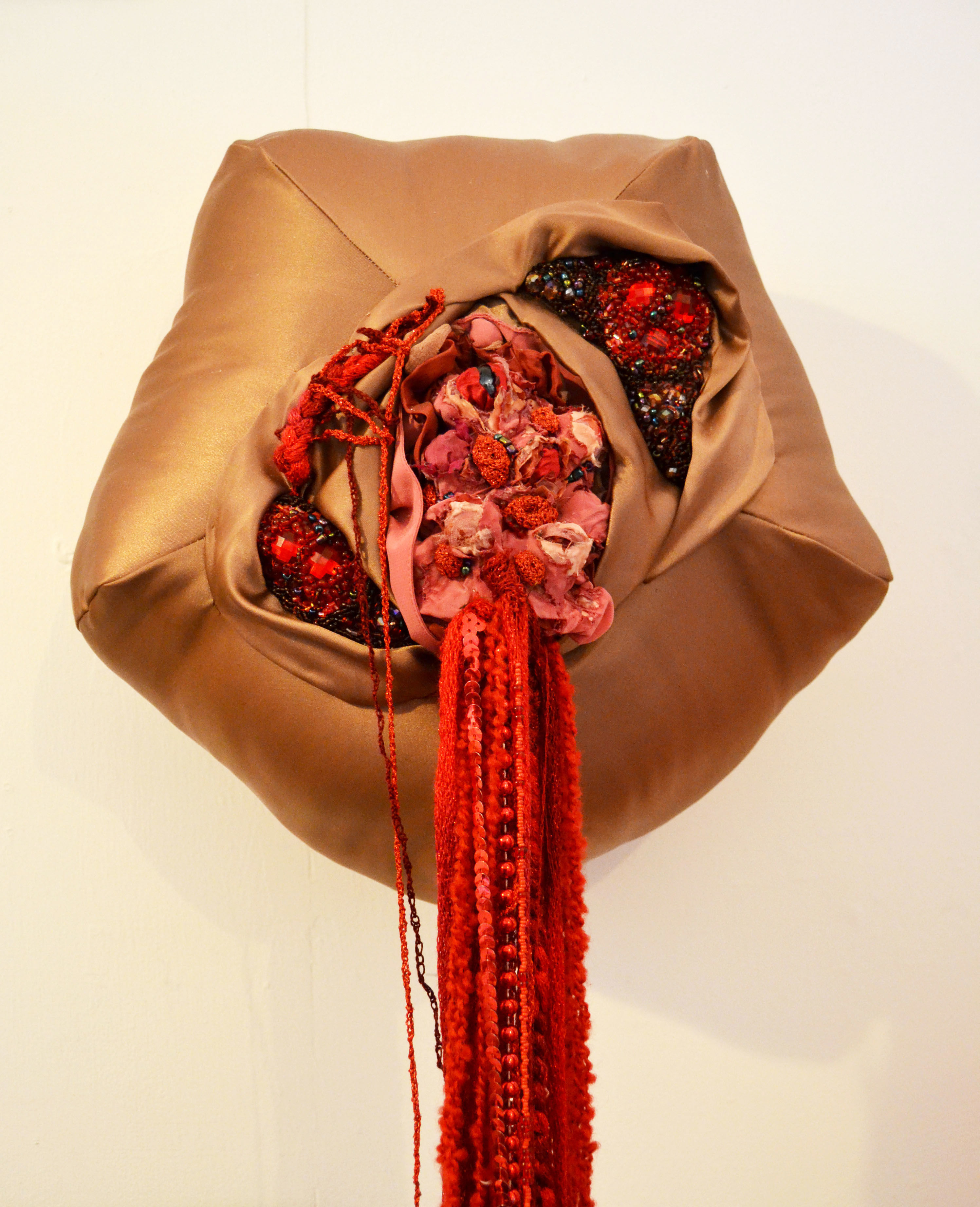

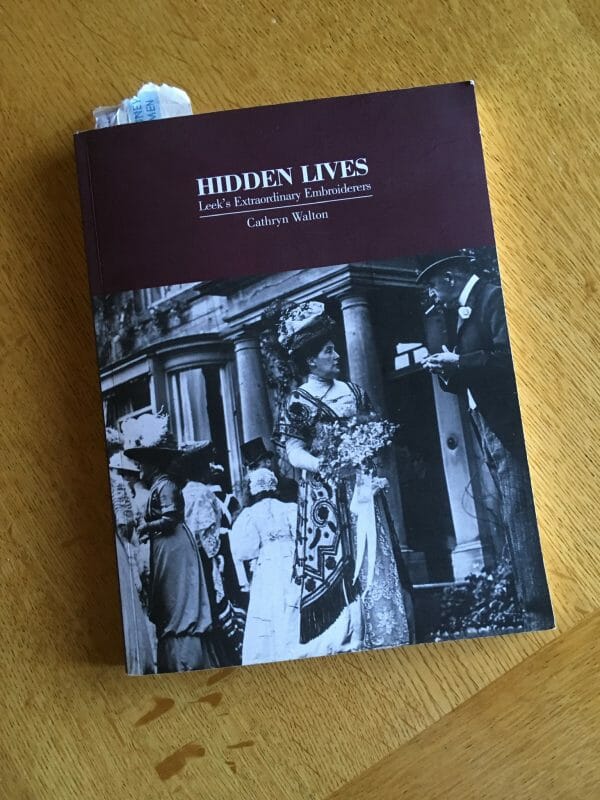

In the 1880s Thomas Wardle ran a dyeworks in Leek, Staffordshire mainly dyeing silk. He and his wife Elizabeth became fascinated by the Bayeux Tapestry and the result was that Thomas dyed 100lbs of worsted wool to make a replica, using natural dyes including madder, woad, walnut roots and weld. Meanwhile Elizabeth organised the Leek Embroidery Society to stitch it. The final embroidery, completed in less than a year in 1886, was 230 feet long and was toured across Britain, America, Europe and South Africa before being sold in 1895 to Reading Corporation. You can still see it now in a specially constructed gallery in Reading Museum and read about it in Cathryn Walton‘s excellent book.

Thomas Wardle, famously taught the arts and crafts designer and writer, William Morris, to create colours using natural dyes. By the time William Morris ‘apprenticed’ himself to Wardle at his dyeworks in Leek the firm were largely using the new aniline or synthetic dyes. Together over a period of 2 to 3 years and several visits the two men attempted to rediscover old dyeing techniques, especially using indigo. The exchange left its mark on the town of Leek which still has many Arts and Crafts buildings. It’s also the home to modern dyeworks and the Dyers Arms pub.

But back to the Bayeux Tapestry. When I went to see it a few years ago in Bayeux I also visited the cathedral where it used to be kept. There was an embroiderer also recreating parts of the Tapestry for sale to tourists. I asked him about the wool he was using and whether it had been dyed with the natural dyes used for the original. Maybe it was my poor French but he didn’t appear to have any knowledge of how his materials were produced and I wonder how true that is for many of us crafters today.

William Morris was extremely particular about using traditional dyes. The new aniline or synthetic dyes were still unreliable and he advocated the older dyes and techniques both for their colours and their lightfastness. However, like most 19th century manufacturers he seemed unaware or uncaring about environmental impacts. Recent research has shown that he used arsenic in his wallpapers and rather waved aside growing concerns about its dangers. And at the dyeworks in Leek workers would stand on planks across the River Churnet to rinse the dye from their silk threads and ribbons. The effluent would then continue along the Churnet, into the River Trent and eventually into the North Sea through the Humber estuary. Although there are more controls nowadays, wastewater from textile works is considered the most polluting of all industrial sectors worldwide.

So, what about us? As a craft dyer working from home, I have to be careful about disposing of waste even though I am using natural dyes and I hope I do this responsibly. But we crafters all use materials the origin of which we probably know little in terms of their human and environmental impact. The adverse effects of the industrial dyeing process on water quality are well known, air quality impacts are less well-documented. But try Googling ‘embroidery thread environmental impacts’ and see how little information is out there. Let’s exert some consumer pressure and see if we can change that.