I can’t be the only one here who sighs (and maybe even comments) when people say ‘tapestry’ when they mean needlepoint. The confusion between the terms is hardly surprising though – the technicalities of construction method of different textiles is quite a challenge.

Real tapestry is woven, although not in the same way as cloth, and needlepoint (as I am sure I don’t need to tell readers of Mr X Stitch, but just in case) is stitched. Needlepoint had a period of huge popularity in the 17th century and in many ways copied the style of traditional, woven, tapestry – most often used for wall hangings in large houses. The critical factor in the use of needlepoint on chair covers, hanging and table coverings is that it could be (although wasn’t always) made in the home and could easily be worked in small scale. Tapestry is another thing entirely, and not really suitable for domestic production.

This post, and the second one next month, aim to give you a basic background on Medieval and later Tapestry, of the type you see in stately homes around the UK and in museums in many parts of the world. I hope that you will be able to put right those that comment on the beautiful ‘stitching’ (it is WOVEN) and the leisured ladies that made it (they DIDN’T). We’ll start with looking at the context for tapestries.

The reason that tapestries appear in posh houses and museums is that they were owned by the very wealthiest of society. The reason they were owned by noblemen and royalty is because they were the only people who could afford them. Woven wall hangings, depicting religious scenes, legends and myths or courtly activities, were amongst the most expensive consumer goods available in the late middle ages (by which I mean about 1350-1550ish). Like decorating your walls with the most expensive paintings today, pretty much, although much warmer.

They certainly did act as insulation in stone buildings, but they were not hanging up in dusty, draughty castles with bare stone walls and holes for windows, they were hanging in highly-decorated, luxuriously furnished, plastered and painted chambers with massive fireplaces and windows within castles. They could also be taken down, rolled up and moved to your other residences when your household travelled, which you couldn’t do with wall paintings (which the less wealthy might have on their walls instead).

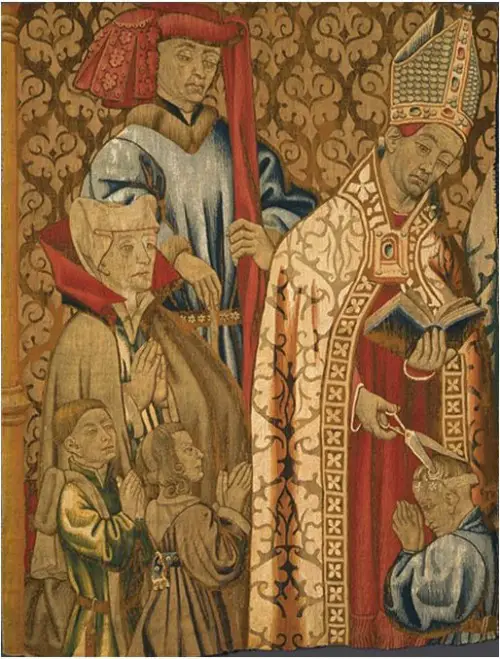

So we know that rich people owned them – but why? Having tapestries in your home showed that you had loads of money which was a necessary part of showing your status in society, your power and your influence, all of which were vital if you were to make the most of your noble birth and social standing. Being rich enough to commission a Tapestry was a big deal and the subject matter you chose was also important to send out a message about your world, your intentions and your superiority to those visiting your home such as officials, fellow nobles or churchmen.

Medieval people understood about imagery and symbolism, particularly religious scenes. You might choose a Tapestry of the life of a particular saint that reflected how you wanted people to see you – humble, merciful, pious or generous. Battle scenes could help to reinforce your power and invincibility. Romantic or courtly scenes would give an impression of what a fine gentleman you are.

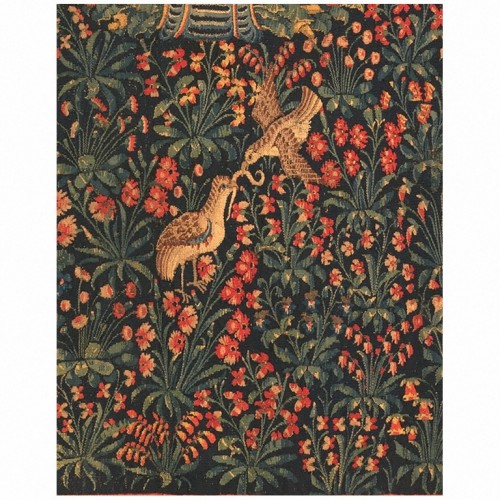

Alongside the major scenic tapestries, there were plenty that were of a more general subject matter such as pasture or flowers on a plain background, known as verdure. These could be purchased quickly, off the peg, rather than needing lengthy commission lead-in times. Many of these survive in houses and museum collections but are usually more battered, patchworked, repaired and generally bodged about as they were inevitably less valuable than those which a nobleman might have commissioned especially for their new wing.

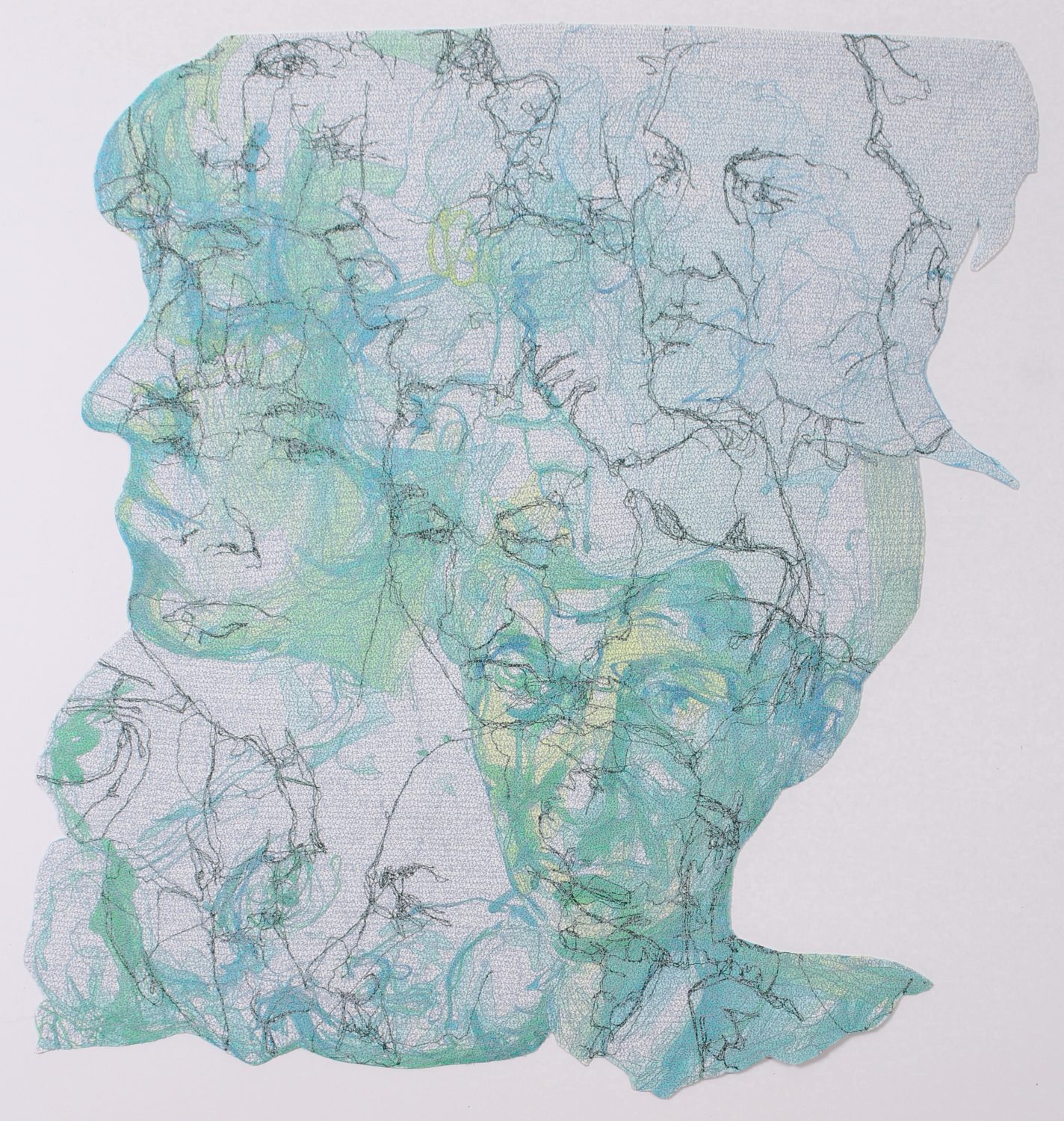

In my next post, I’ll explore how they were made, where, who by and with what materials. If you want a little homework before then I can highly recommend The Lady and the Unicorn by Tracey Chevalier which has very accurate descriptions of the commissioning and social context around the making of a 15th century Tapestry – and it is a good read! You might also like to read a little about contemporary Tapestry artists such as Erin Riley and Hannah Ryggen.

—

Ruth Singer Books – Get yours from our Amazon store!

– Get yours from our Amazon store!

[column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

[/column]

[column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

[/column]

[column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

[/column]