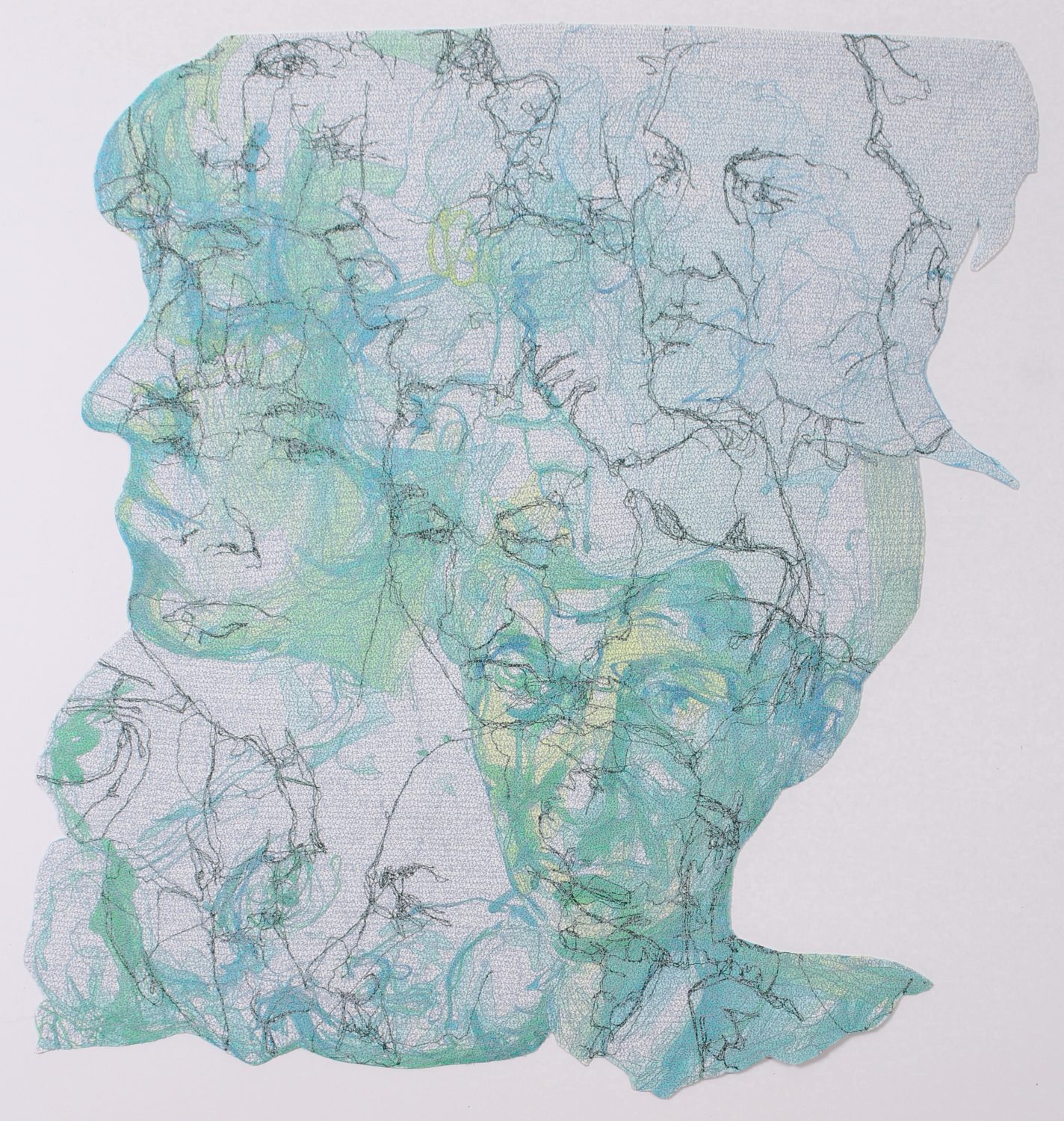

Welcome to Ghost In The Embroidery Machine, where you’ll get all the tips and tricks you need to become a dynamic digital embroiderer, thanks to the wit and wisdom of Erich Campbell!

It’s time for another edition of our seldom-seen advice column, Ask the Ghost in the Embroidery Machine! Today we have a home embroiderer with a bone to pick with palette-thrashing digitizers, but all is not what it seems…

Dear Ghost,

Why do the colors that show up in my software or on my machine never match the ones I see when I buy the design? Why do different file formats switch colors around or completely change them? Don’t digitizers just use the right colors?

Confused by Color-Charts

Dear Confused,

As a digitizer myself, this may sound defensive, but it’s somewhat out of the digitizer’s hands when it comes to outputting a machine embroidery design file with the ‘correct’ colors.

There are many reasons why the colors don’t come out the same as the sample picture, but the easiest explanation is that the files that some machines require have a limited set of embedded colors built into the specs of the file type or contain no thread color information at all.

In order to make a little more sense of why digitizers are stuck with the limitations of the files, let’s take a look at how they work and file types involved in getting your machine running.

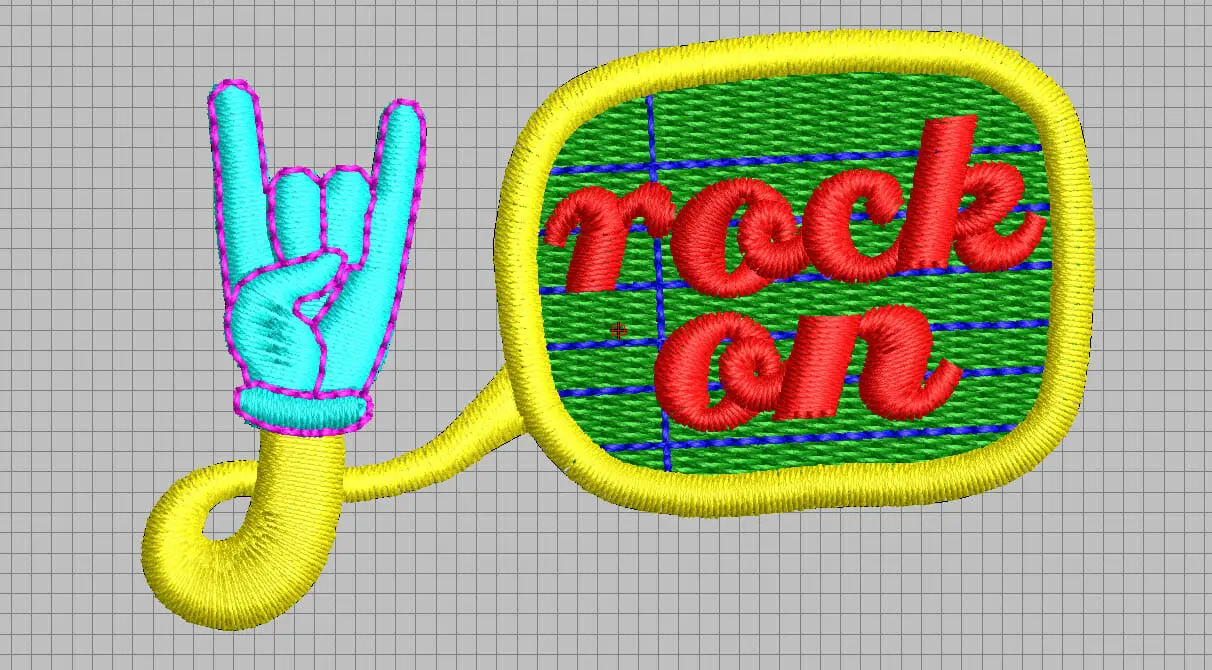

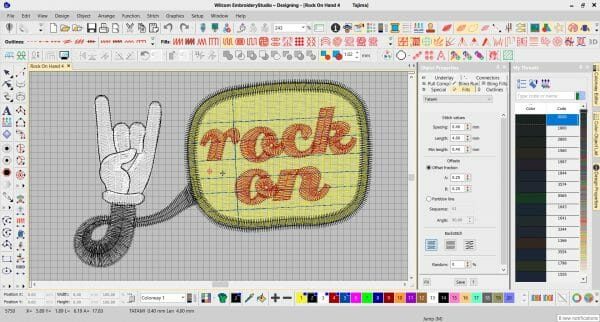

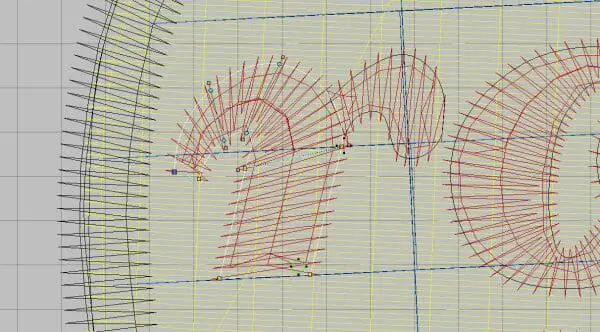

When a digitizer creates a design, the digitizing software saves their design in what’s called a condensed, native, or work file. This file is specific to the software they use and is not formatted in a way that embroidery machines can read. Digitizers draw shapes delineating areas or outlines that are filled or lined with a certain kind of stitching.

If you are someone who has used graphic design software, these shapes are a lot like vector graphics with an important distinction; a digitizer doesn’t just draw shapes but also specifies settings for each shape including stitch type, stitch length, density, stitch angle, start and stop points, placement in the sequence, density of stitches, and any other pertinent information that the digitizing system needs in order to generate the stitches to fill the shape.

In the native file, a digitizer can create or edit shapes, resize elements, re-sequence elements, change the stitch parameters for a shape, and add machine commands.

Native files also allow for reprocessing; you can make changes and the stitches will be regenerated according to settings set during the digitizing process.

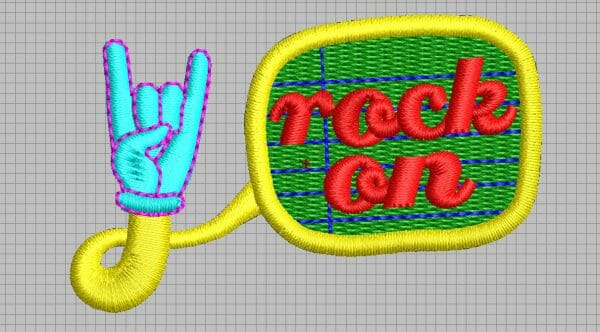

As for the colors in this file, a digitizer can set one or more ‘colorways’ or palettes. These are usually specific to a thread brand with which the digitizer is familiar, though many work initially in colors that do not match the art, but rather are easy to see over background templates to make it easier to see the work as it’s done, using a second ‘colorway’ with the more accurate matches to visualize the finished product.

When the digitizing is complete and it’s time to run the design, the digitizer must output the design into a machine format.

The machine or ‘expanded’ file formats are those with which you are probably the most familiar; these formats are the ones the machines understand.

Instead of being filled with shapes and settings, these small files consist mostly of coordinates where the stitches are placed, codes that tell the machines when to lift the needle, stop for color changes or automatically change color, and or engage automatic trimmers. These files have explicit coordinates for every needle drop, but don’t contain the original shapes and information in the work file.

Some formats for home machines have a palette of colors specific to the format and might contain hoop sizes to prevent you from using a hoop to small for your design, whereas commercial embroidery formats like the industry standard DST from Tajima, do not contain any color or hoop size information whatsoever.

The commercial machine embroidery design formats were born of a time when machines’ control units had no graphical capabilities nor preview screens.

The commercial machines trust that you will have a list of colors in the order that they need to be implemented, and with a multi-needle machine, that you’ll program the machine to switch to the right colors as they are threaded for each run. Further, the commercial machine trusts that you’ve selected a hoop that will fit your design.

Want more digitising tips?

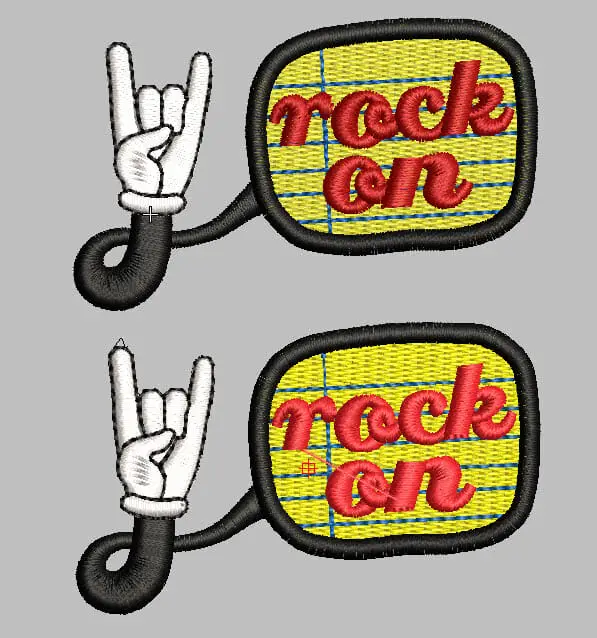

The problems with color arise when saving a design to these machine formats. Most software will try to match the colors you’ve selected in the digitizing process to those that are built into the software format you’ve chosen, if that format has colors in its spec.

What this can mean is if you used an odd fluorescent color of green for your creation and specified your unique thread in the work file, upon saving that file to a home format that does have a color palette, that color in your sequence will be matched to the closest color available in the machine format’s set palette; that may be a vastly different color, like a leaf green, if nothing close to your original neon selection exists in the file’s specs.

Therefore, when you open your design in software or on a machine with a color screen, it will show that closest match color, not the original color, as the original color was lost in the conversion.

Now, if you save the design as a commercial format, the color of the thread is lost entirely. The commercial machine embroidery design files only tell the machine when it needs to move to the next specified needle or when to stop the machine for rethreading.

As no colors are stored in these files, a commercial file opened in embroidery software or on a color-screen machine will show the colors with a default palette built into the software; this means that if your default palette has blue for a first color, then lemon yellow, then tomato red; every commercially formatted file you open will start with that same blue, yellow, and red as the first three colors in its sequence when displayed.

Commercial embroiderers like myself often don’t see the problem because we’ve been conditioned to accept the situation; we check the list, thread the machine accordingly, and check the sequence when we set up the needles.

As for saving that data from job to job, we largely store our design information either in the original work files that do maintain our chosen colors or in cataloging software that allows us to store information for each embroidery job we execute. The file formats have so long been divorced from the colors that we sometimes take it for granted that you need a secondary way to store color and run information.

Luckily, home embroiderers now have software solutions available that can serve the function of our information management software. My suggestion for home embroiderers is to check whether or not their current software has a design cataloging function that can store colorways and if not, get third-party software that does. At the very least, you can elect to use a single folder with saved preview images and color sequence sheets matched by name to the designs in your collection.

Whatever you do, the best practice is to have a reliable way that you store your files, save all of your color sequence sheets, and stick with it religiously.

Machine Embroidery Design Management

My advice beyond keeping your files organized is to keep some sort of embroidery journal, preferably digitally so that it can be searched. That way you can store your particular colors for a design and the project on which you used, it along with other pertinent information about each run.

The benefit of storing this info yourself rather than having attached to a file format is that you can store alternate colorways for different projects using the same design or a combination of designs, as well as the settings and supplies you used to make each work.

Keeping an embroidery journal will mean that you never have to search again for that thread or design you used on some project a number of years ago and thus never having to do the same experimentation twice. It might be easier if the design file could store every bit of information itself, but the added information you can store, like the stabilizer you used or the way you altered tension to make a strange thread run correctly, will be invaluable to you if you need to replicate your work or some technique you developed in said work for a future project.

Nothing will make that first time you re-color the design or have to blindly trust the color sequence given you any more fun, but it’s a small price to pay to learn how to document your work and keep your information at the ready.

Erich Campbell is an award-winning machine embroidery digitizer, designer and a decorated apparel industry expert as well as an industry educator appearing at several trade-shows as well as teaching online. He frequently contributes articles and interviews to embroidery industry magazines such as Printwear, Images Magazine UK, and more as well as to a host of blogs, social media groups, and other industry resources.

Erich is an evangelist for the craft, a stitch-obsessed embroidery believer, and firmly holds to constant, lifelong learning and the free exchange of technique and experience through conversations with his fellow embroiderers. A small collection of his original stock designs can be found at The Only Stitch