I hope everyone enjoyed the last bits on redwork, I thought it was only fitting that we look at blackwork this week!

Unlike many of the traditions we look at here, blackwork does not appear to have secret origins that we have to dig for. It is widely established that blackwork arrived in spain during the Al-Andalus period that lasted from 711 until the Reconquista in 1492. Islamic influence can still be seen there in art, architecture, and most relevantly to us, blackwork.

Embroidered Hanging, Eastern Iran or Afghanistan, 14th century

Embroidered Hanging, Eastern Iran or Afghanistan, 14th century

It is generally accepted that these moorish designs have their roots in a taboo against rendering human figures for fear of creating idols, but some pictorial and figurative work can be found in every age of Islamic art. The arabesque does however appear as a prominent motif. Generally an arabesque is a repeating geometric design, oftentimes overly stylised flowers and plants. Moroccan tile and Persian rugs are are excellent examples. Wiki has a nice article on this style that explains, “To Muslims, these forms taken together, constitute an infinite pattern that extends beyond the visible material world. To many in the Islamic world , they concretely symbolise the infinite, and therefor uncentralised nature of the creations of Allah. Furthermore, the Islamic arabesque artist conveys a definite spirituality without the iconography of Christian art.” When we look at traditional blackwork patterns, we see that this is the favoured design.

Sampler fragment, Mamluk period, 1300-1420. Silk embroidery

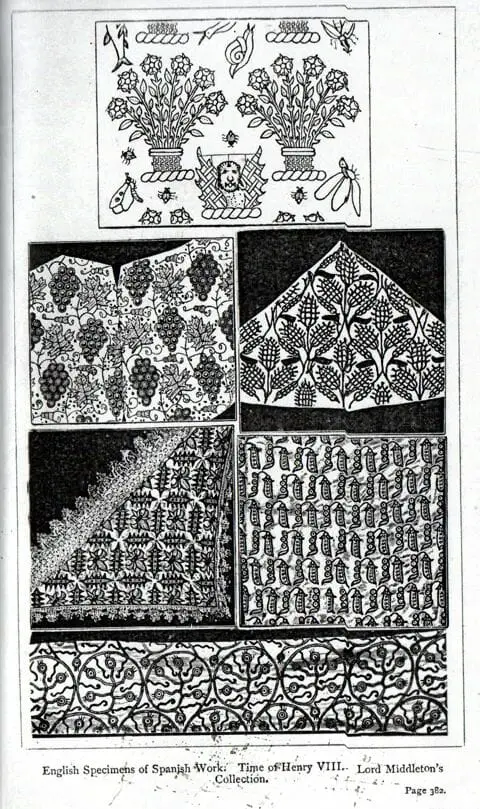

The earliest reference I have for blackwork is in Needlework As Art, 1886 by Lady M. Alford. She says that Catherine of Aragon “introduced the Spanish taste in embroidery”, and this “continued to be the fashion down from Mary Tudor who remained faithful to the traditions of her mother and grandmother’s work.”

English specimens of Spanish Work: Time of Henry VIII from Needlework as Art

Lady Alford cites an inventory of Lord Monteagle’s property from 1523 found in the Piblic Record Office, (presumably accessible at the time of her book’s publication), that contained a piece labeled as Spanish Work. It is described as “eight partlettes garnished with gold and black silk work”. Apparently a “partlette” is a kerchief. She goes on to say that Catherine of Aragon “learned the craft from her mother, Queen Isabella, who always made her husband’s shirts.” Lady Alford takes special care to note that “To make and adorn a shirt was then an artistic feat, not unworthy of a queen.” I think many of us would agree with that statement. Queen Isabella also instituted “trials of needlework amongst her ladies.” When she comes to Catherine she says, “In the days of her disgrace and solitude, Catherine turned to embroidery for solace and occupation.” The poet John Taylor (1578-1683) says of Catherine, “Virtuously, Although a queen, her days did pass, in working her needle curiously.” I know I’ve quoted quite a bit from Lady Alford’s book, but it is a rare volume and pretty fascinating. Expect more in this article.

Henry VIII by Hans Holbein the Younger (note the blackwork)

Henry VIII by Hans Holbein the Younger (note the blackwork)

So we have established blackwork or “Spanish work” in Spain, but how did it become common in England? Well, when Catherine of Aragon married Henry VIII in 1508, she brought the style with her.

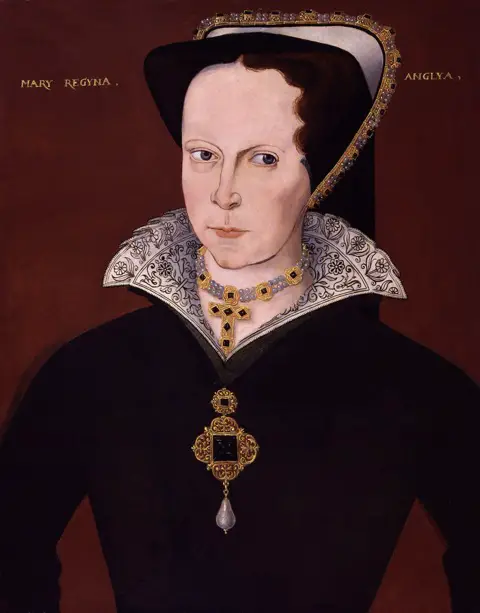

Queen Mary I, unknown artist, 1555. (notice the blackwork collar)

Queen Mary I, unknown artist, 1555. (notice the blackwork collar)

According to Lady Alford their daughter Mary Tudor, “…Was Spanish in all her tastes and we have lists of her smocks all worked in Spanish stitches, black and gold or black silk only.” When we get to her sister Elizabeth, Lady Alford tells us that Queen Elizabeth was an avid practitioner of needlework, but Spanish work fell out of favor during her reign in part to the changing political landscape. This statement contradicts the information found in Catherine Amoroso Leslie’s book, Needlework Through History: An Encyclopedia. Let’s leave Lady Alford here and pick up with Catherine Leslie.

Portrait of Jane Seymore by Hans Holbein the Younger (note the blackwork)

Portrait of Jane Seymore by Hans Holbein the Younger (note the blackwork)

She says that far from blackwork being abandoned, a new style developed under Queen Elizabeth. She says, “English design was beginning to emerge as an individual style with delicate flowers, scrolling vines, and strong outlines filled with repetitive patterns.” She also says that the blackwork tended to be accented with gold thread and occasionally, sequins. I found this next bit especially interesting because I’m not only a stitcher, I’ve been a printmaker for nearly twenty years. Actually, the main reason I got into needlework is because I realized my prints would work well as embroideries. Catherine Leslie says, “Designs were influenced by wrought-iron scroll work, and the new availability of printed materials. Black and White plates with images of native plants and allegorical stories were reproduced in black and white embroidery.” She goes on to say, “…Sometimes directly copied from engravings and woodcuts. Sometimes motifs would be filled with small running stitches called seedling or speckling stitches, which imitated the printer’s ink.”

Unknown lady, portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger. (Again, blackwork)

Unknown lady, portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger. (Again, blackwork)

Speaking of art, you may have noticed that many of the paintings I’ve included in this article were done by the same hand. From Benet’s Reader’s Encyclopedia- “Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1553) Holbein studied and worked in Basel and was led by the artistic depression ensuing from the Reformation to undertake a trip to England (1526-28) and finally to settle there in 1530. He executed smoothly finished, carefully detailed, precisely drawn, and richly colored portraits and religious paintings.” Why am I giving so much information on him? Because many of our blackwork references come directly from his portraits. So much so, that the style of reversible blackwork stitch found so often in that period is called a Holbein Stitch.

Of course blackwork is found in other European regions. Hungary, Yugoslavia, Serbia, and Romania also have blackwork. There it seems to be used in the traditional style of decorating cuffs and collars. Catherine Leslie reminds us again that this is “related to the superstition that embroidered edges on clothing protect the body from evil spirits.” I’ve decided not to explore these regions as thoroughly as the Spanish/British tradition because pieces tend to be worked just as often in any monochromatic stitch.

So meet me back here next time when we look at contemporary blackwork!

Reference material for this article included:

- Needlework as Art (1886) by Lady M. Alford

- Needlework Through History by Catherine Amoroso Leslie

- Benet’s Reader’s Encyclopedia, Fourth Edition

- The Medieval Middle Eastern Embroidery Gallery

- And special treat for you! Authentic Egyptian blackwork pattern! click HERE!

_______________

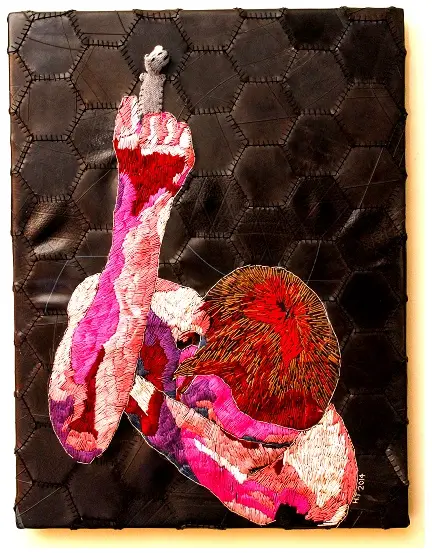

Penny Nickels is a printmaker that started playing with needles with tremendous effect. She and her husband, Johnny Murder, have been described as the “Bonnie and Clyde of Contemporary Embroidery” and you can discover the power of her creativity at her blog.