Hello everybody! This week we’re going to look at the history of crewel! Yea! Exciting.

Crewel is embroidery typically done with wool thread. Although wool embroidery is known from the earliest times, crewel generally uses two ply woollen yarn and was typically worked on linen. According to Needlework Through History, “The word ‘Crewel’ can be found in English records back to the thirteenth century. It may have come from the Anglo-Saxon, cleow or clew, meaning ball of thread.” This definition is especially interesting to me because of my love for mythology. When Daedalus teamed up with Ariadne to help Theseus navigate the labyrinth and slay the Minotaur, they gave him a ball of thread, a clew to help him find his way in and out. Clew also meaning “clue”. A hint to help him solve the labyrinth.

Crewelwork spread through England from 400 c.e. to 1400 c.e., but the earliest examples date from the first century b.c.e. from northern Mongolia. There is also Biblical reference to alter garments and temple hangings that are decorated with wool embroidery, as well as an archeological find of wool stitching on an Egyptian tomb hanging dating from the 4th century c.e. Essentially, you can make a safe bet that any region that has needlework and wool has some variation of crewel.

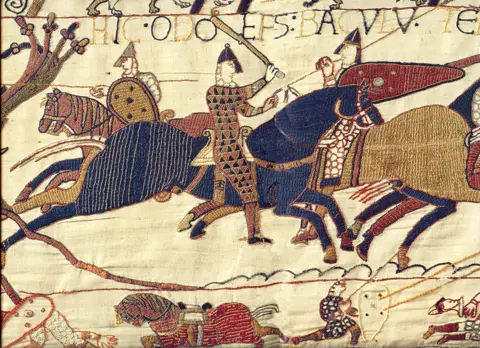

Because wool, and textiles in general are extremely fragile in the face of time, few early examples exist. Fortunately, one of the most famous examples of needlework happens to be crewelwork, The Bayeux Tapestry.

We’ve talked about the Bayeux Tapestry before in Needle Exchange, but it’s worth going over again. Contrary to its title, the Bayeux Tapestry is not a tapestry at all. Said to have been completed around 1077, It€™s an embroidered cloth that measures 70 meters long. It depicts the events of the Norman Conquest featuring William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings.

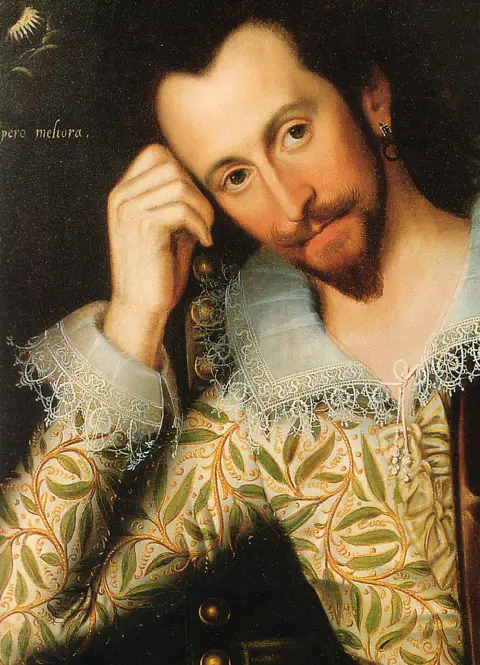

In the mid sixteenth century, steel needles became less expensive and more readily available, which allowed more people to do finer embroidery. Queen Elizabeth, who we’ve talked about before, was a great lover of needlework. It was during her reign that crewelwork reached the height of popularity, continuing well into the seventeenth century. It became known as Jacobean Embroidery during the reign of King James the 1st.

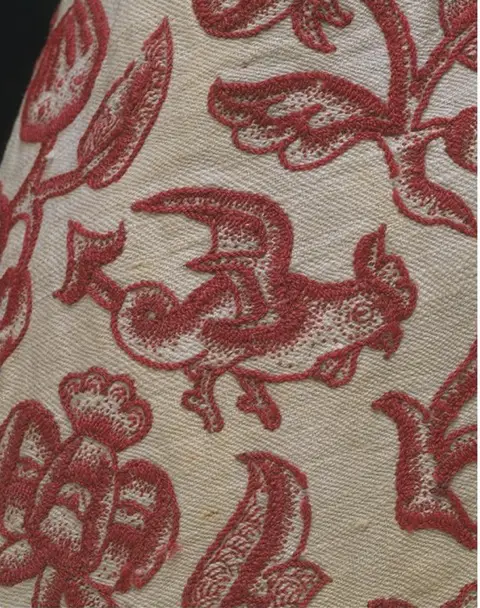

Example of Jacobean Embroidery 1614

Example of Jacobean Embroidery 1614

Example of Jacobean Embroidery 1610

Example of Jacobean Embroidery 1610

Because wool, and other protein fibers hold dye so well, it’s not unusual to see bright colors when we look at crewel, even from the earliest times.

These crewel worked pockets from the early eighteenth century are a beautiful example of the lush color that comes with dying wool. The floral motif is also extremely common in crewelwork, along with The Tree Of Life design. According to Needlework Through History, those designs are “a result of cross-cultural exchange between East and West. Europeans went to China and then India, seeking spices to help make unrefrigerated meat palatable. Along with spices, they brought back textiles and other objects which influenced Western design. We also saw examples of this when we looked at blackwork, specifically the Arabesque.

These crewel worked pockets from the early eighteenth century are a beautiful example of the lush color that comes with dying wool. The floral motif is also extremely common in crewelwork, along with The Tree Of Life design. According to Needlework Through History, those designs are “a result of cross-cultural exchange between East and West. Europeans went to China and then India, seeking spices to help make unrefrigerated meat palatable. Along with spices, they brought back textiles and other objects which influenced Western design. We also saw examples of this when we looked at blackwork, specifically the Arabesque.

Although its popularity waned in the late eighteenth century in the U.K. for new styles such as stumpwork, crewelwork traveled to North America where it remained popular.

William Morris is credited with reviving crewelwork in the mid nineteenth century when Morris and Company lead a movement that came to be known as “arts and crafts”. According to wiki, “Morris became active in the growing movement to return originality and mastery of technique to embroidery, and was one of the first designers associated with the Royal School of Art Needlework with its aim to ‘restore Ornamental Needlework for secular purposes to the high place it once held among the decorative arts.'”

Detail of crewelwork on linen designed by William Morris in 1877

So that wraps up our brief jaunt through crewelwork. Join me next third Friday for a look at some contemporary pieces.

——————

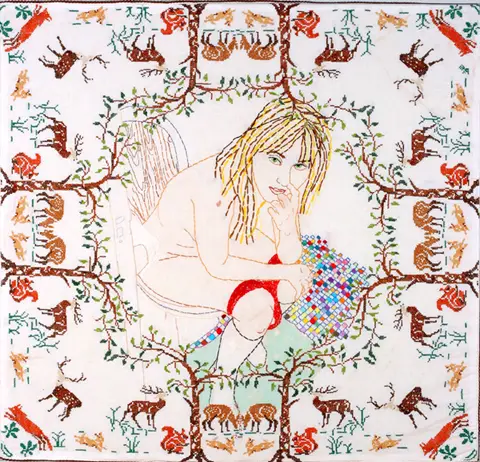

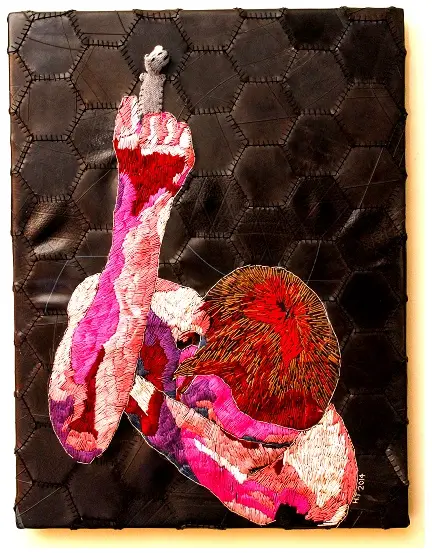

Penny Nickels is a printmaker that started playing with needles with tremendous effect. She and her husband, Johnny Murder, have been described as the “Bonnie and Clyde of Contemporary Embroidery” and you can discover the power of her creativity at her blog.

——————

References for this article include Needlework As Art (1886) by Lady M. Alford

Needlework Through History by Cathrine Amoroso Leslie

18th Century Embroidery Techniques by Gail Marsh